Pete Shelley

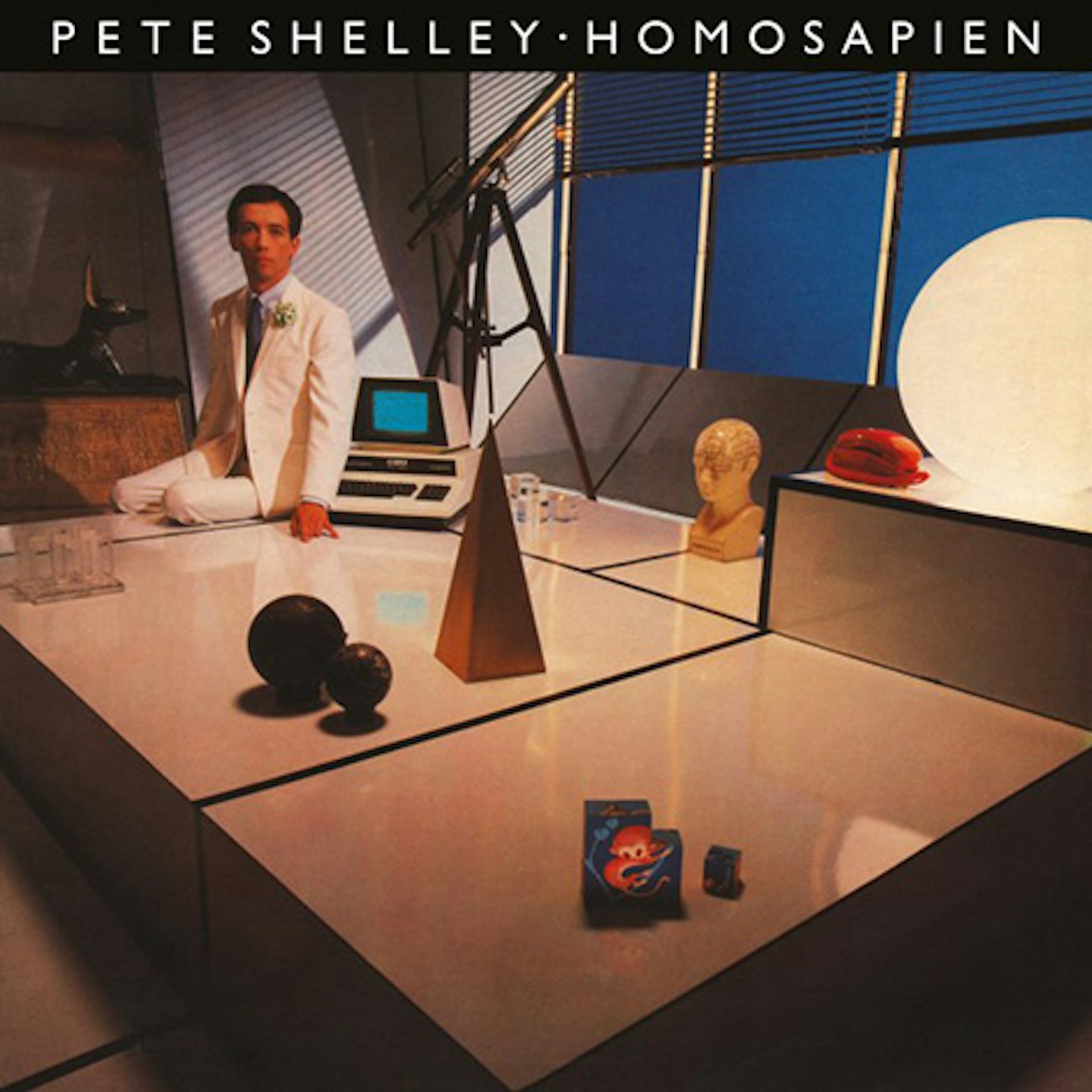

Homosapien

★★★★

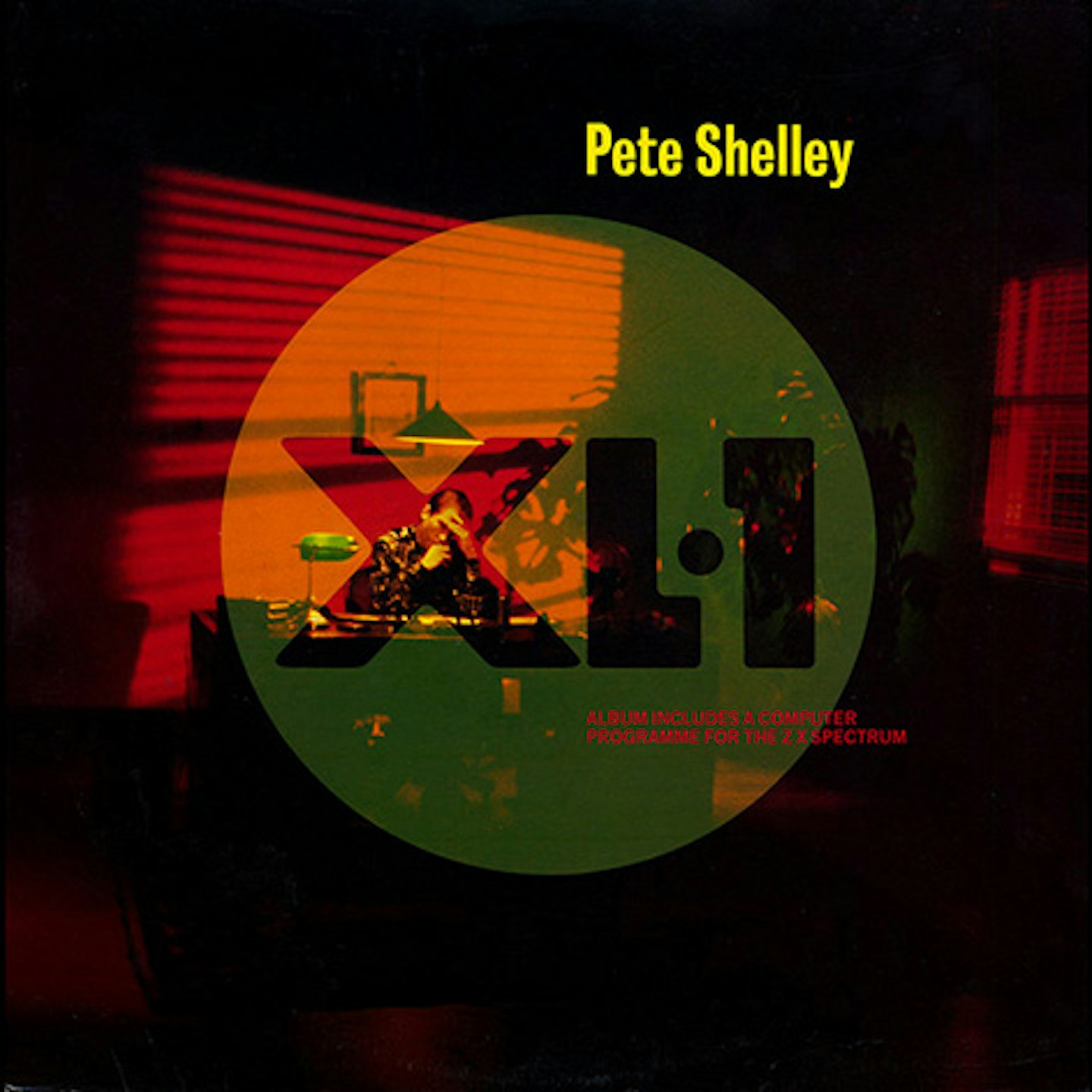

XL1

★★★

DOMINO

Writing in his personal fanzine Plaything (street price, 3p) in 1978, Buzzcocks singer Pete Shelley was already waiting impatiently for the great post-punk leap forward. “The next wave will start from where this one has finished,” said the one-time National Coal Board computer operator. “So don't slacken off now, but slip into a higher gear. There is still a lot more we can do.”

Getting his audience – and his bandmates – to buy in to his vision for the future proved to be a challenge for Shelley. A thunderous dancefloor banger (even more impressive at its full 12” extension), his September 1981 debut solo single Homosapien deployed the same electronic toolkit that producer Martin Rushent was using to make the Human League’s breakthrough album Dare. However, the unambiguously man-on-man lyrics – “I’m a cruiser you’re a loser, me and you sir” and especially “homo-superior in my interior” – proved far too racy for mainstream consumption.

Back in circulation after decades in the bargain buckets, the accompanying Homosapien LP – and its follow-up XL1 – represent Shelley’s kamikaze attempt to reinvent himself for the 1980s, the genial, five-foot-six, Jackie comic boy next door re-cast as a futuristic 12-string troubadour.

Aggressively modern from the outside, Homosapien is also stuffed with material Shelley wrote as a teenager for his pre-punk glam band Jets Of Air, with the record’s queasy shifts of tone from existentialist ennui to Glitter Band feather-boa twirling suggesting a big in-joke that Shelley isn’t entirely sure he wants anyone to be in on. “Do it like a lion baby, do it in our lairs,” he shrieks on the ludicrously camp Just One Of Those Affairs. “Do it like the birds and bees and arctic polar bears.”

“I never felt I could play these songs with the Buzzcocks,” Shelley explained as he spoke to Sounds at the time of his debut album’s release in January 1982. However, as he embraced life outside the ur-Manchester guitar group, there was a sense – briefly – that everything was back in play.

Shelley had experimented with primitive electronics when he was still Pete McNeish – he irked some of his fellow Buzzcocks by releasing a solo album of his 1974 oscillator doodles, Sky Yen, in 1980. However, he made his name by reinventing the love song with a run of killer Buzzcocks singles – What Do I Get?, Ever Fallen In Love, Promises, Everybody’s Happy Nowadays – spawning all indie-pop with a combination of brilliant melodies and a gender-neutral songwriting language stripped of alpha-male baggage.

He got bored with the punk rock 9-to-5 quickly, though, and felt he was being held back as former Buzzcocks support acts like Joy Division and the Gang Of Four took their place on the cover of NME. His band made powerful strange records of their own – 1979’s daunting A Different Kind Of Tension and the run of three 1980 singles (Are Everything, Strange Thing, Running Free) that they envisaged as an album by instalments – but as they struggled to make ends meet, seemed unwilling to risk messing too much with the formula.

There was limited enthusiasm for the prospect of a fourth Buzzcocks album when the band convened at the start of 1981. Eager to relight Shelley’s fire, the band’s regular producer Rushent persuaded the singer to come and record some demos at his newly-equipped Genetic studio, and something clicked. “We started recording Homosapien with just me on a 12-string, a drum synthesizer, a Roland Micro-composer and a big Roland synthesizer,” Shelley told Trouser Press in 1982. “Within a day we were sitting listening to the finished song.” Excited at the prospect of a new direction (and a simpler way of working) Shelley quit the Buzzcocks in March 1981, and signed for Rushent’s Genetic production company, with Island picking him up as a solo act.

One of the greatest misses of its age, the title track sets a daunting pace for the Homosapien LP, but if there is nothing else here quite as monumental, there is plenty more eccentric stuff to explore. I Don’t Know What It Is comes on like the sexy half-brother of the Buzzcocks Something’s Gone Wrong Again, while Pusher Man – another Jets Of Air cast-off – is a ludicrously arch spin on saying no (or maybe yes, occasionally) to drugs.

Influenced by a significant acid intake, Shelley’s later-period Buzzcocks songs skewed fairly cosmic, and he continues to pick at the fabric of existence on Homosapien. He is a slave to the infinite rhythm on electronic raga I Generate A Feeling, singing: “Everything is different my perceptions aren't the same, when I can't believe the wonder that surrounds me.” Qu’est Que C’est Qu’est Ça, meanwhile, contains a juddering chord change worthy of his Buzzcocks co-founder Howard Devoto’s Magazine, and further questions as to the essence of being. “Is this all that there is or are there things that we can't see?” Shelley asks, leafing through his personal X-files. “Maybe meditation could improve my concentration.”

Maybe that was true, but the magic of Homosapien comes from the fact that he changes direction so frequently, and that the technology seems to enhance Shelley’s innate ear for a tune. Yesterday’s Not Here, Keats’ Song and his sombre closer It's Hard Enough Knowing are all among his best romantic songs, and plenty more great material was destined for B-sides; his futuristic mission statement Witness The Change, the excitable Love In Vain, and his coy epistle to his mistress, Maxine.

Homosapien captured an exuberant moment when everything seemed possible, but the magic had worn off by the time of 1983’s XL-1. If his debut album came with the thrill of being at the cutting edge, its follow-up (free ZX Spectrum programme notwithstanding) feels more like hard work. Shelley was evidently not a prolific writer and while he coughs up some moderate floor-fillers (the euphoric title track, Many A Time) and some pleasingly lovelorn bits (You Know Better Than I Know, Twilight), XL-1 feels like an attempt to do Duran Duran tailoring on a C&A budget.

Shelley persisted with his dreams of being an electropop sophisticate, making a third LP – Heaven And The Sea – in 1986, and getting nowhere with synth-pop combo, Zip! He eventually bowed to public demand by reforming the Buzzcocks, who played regularly and recorded fitfully until his death in 2018.

Homosapien, though, feels like it may be the purest distillation of what Shelley had to offer; sexually ambiguous, playful but also sort of inscrutable. Honouring that promise he made in Plaything, he and Rushent slipped into a higher gear, seeking to ride the next wave with a novel take on pop modernism. That it imploded on launch may owe something to exactly what you could – or couldn’t – say on the radio in 1981. The buzzsaw fizzbombs he made in the Buzzcocks first incarnation remain his musical calling card, but Homosapien underlines that – whatever his bandmates might have thought – there was still plenty more that Shelley could do.

Homosapien and XL-1 are our June 6 on Domino.

ORDER HOMOSAPIEN: Amazon | Rough Trade

ORDER XL-1: Amazon | Rough Trade

Track listing:

Homosapien

1. Homosapien

2. Yesterday’s Not Here

3. I Generate A Feeling

4. Keat’s Song

5. Qu'est-ce Que C'est Que Ça

6. I Don't Know What It Is

7. Guess I Must Have Been In Love With Myself

8. Pusher Man

9. Just One Of Those Affairs

10. It's Hard Enough Knowing

11. In Love With Somebody Else

12. Witness The Change

13. Maxine

14. Love In Vain

15. Homosapien (Elongated Dancepartydubmix)

16. Witness The Change/I Don't Know What Love Is (Dub)

XL-1

1. Telephone Operator

2. If You Ask Me (I Won't Say No)

3. What Was Heaven?

4. You Know Better Than I Know

5. Twilight

6. (Millions Of People) No One Like You

7. Many A Time

8. I Just Wanna Touch

9. You And I

10. XL1

11. Many A Time (Dub)

12. Telephone Operator/I Just Wanna Touch/If You Ask Me (I Won’t Say No)/(Millions Of People (No One Like You) (Dub)

Get the latest issue of MOJO for the definitive verdict on all the month’s essential new releases, reissues, music books and films. More info and to order a copy HERE!