In October 2005, as Born To Run’s 30th anniversary box set was being readied for release, MOJO was granted a remarkable interview with Bruce Springsteen, during which, backstage in Chicago, the singer revisited the making of his breakthrough album and its follow-up, Darkness On The Edge Of Town. In this interview taken from MOJO’s new Bruce Springsteen special The Collectors’ Series: Bruce Springsteen Essentials, MOJO's Phil Sutcliffe pulls up a chair to hear about Springsteen's childhood in New Jersey, political awakening, and the creation of two very different masterpieces…

Chicago’s United Center is home to the Bulls, the NBA basketball team who used to win everything back when Michael Jordan was king. It’s the usual big, dark cave. But when, for the soundcheck, MOJO takes a solitary spot in the semi-darkness among the 9,000 empty seats, the place bears a strangely private air. Bruce Springsteen is alone on stage at the piano talking through the mic to a soundman in a remote location, marked only by a reading lamp. Nobody else is visible except when a tech walks on with the next instrument to check.

Springsteen’s wearing a sartorial hodgepodge of suit jacket, blue jeans and baseball cap – reversed part way through, the only whimsical moment in the entire process. He sings a verse or two of each song – Saint In The City, You Can Look (But You Better Not Touch), Jesus Was An Only Son – working briskly through piano, electric piano, pump-organ, various acoustic and electric guitars, harmonica, a ukulele (given to him by Eddie Vedder) and finally autoharp. He checks out the “bullet” mic, beloved of Tom Waits, which twists his voice into a deranged howl for Johnny 99. Everything’s in good order and requires no comment beyond “OK” and muttered thanks as each new instrument is handed over.

When he’s done, he picks up some papers, shoves them in a battered black briefcase, walks off on his own like some slightly bohemian clerk on his way to the office, and goes straight to his dressing-room.

2005 is a prime year for Springsteen, one that’s drawn the threads of his past and present together. In spring, he released Devils & Dust, the third of his powerful solo-ish and mainly acoustic albums following Nebraska (1982) and The Ghost Of Tom Joad (1995). In November it was the plush 30th anniversary reissue, with bonus DVDs, of Born To Run, the album that made his career. The two records could hardly better represent the extremes of his appeal down the years, from the big adrenalin thrill of youth to the dark knowledge and doubts of middle age (he turned 56 in September).

Born To Run was uninhibited: the appassionato vocals like a street-rough Roy Orbison, the almighty rockin’ R&B grunt and Spector-tinselled grandeur of the E Street Band with Clarence Clemons’ sax in excelsis and Roy Bittan’s piano hinting at dirty concertos. His third album and breakthrough after his first two failed to nail it, it teemed with all-but-doomed youth living it large in a small world, wheeling and dealing, fighting and romancing, chasing a dream of nobody-knew-but-what-the-hell. And it was the last album like that Springsteen ever made.

As a songwriter and musician he moved on into the big world. The broad picture is that, while he never invented a genre nor even experimented much within the idiom, he did bring the whole history of rock’n’roll together with love and verve and imagination and a protean attention to detail. The music was kind of taken care of in the blood, and the soul was right there – anyone who heard what he did when a wordless howl or holler was called for knew what he had inside. But, chiefly, he pulled off his translation from excitable boy to rock’n’roller for the ages by becoming a great storyteller.

In fact, that process of development started on Born To Run with Meeting Across The River, the one slow track, murky with melancholy piano and lonesome trumpet. The stroke that hinted at Springsteen’s narrative gift was that he chose to write the lyric as just one side of a conversation. “Hey Eddie, can you lend me a few bucks / And tonight can you get us a ride,” asks first-person unnamed. From those opening lines all his fears, failures and serial delusions of grandeur hang out there in the empty air, unanswered and exposed, until this poor dope who’s “planning” a stick-up without a car or a gun has finished his fantasy about impressing his wife – “I’m just gonna throw that money on the bed / She’ll see this time I wasn’t just talking.”

By the following album, Darkness On The Edge Of Town (1978), he was committed to developing this craft. It included a crucial stepping-stone in Racing In The Street. Perhaps deliberately confronting the “cars-and-girls” line of criticism that dogged his early years, it started out with a car-obsessed hotrodder in barroom braggadocio mode: “I got a ’69 Chevy with a 396 / Fuelie heads and a Hurst on the floor.” After a bit of boasting about all the races he’s won, he suddenly finds himself thinking about his girl, her love, her ageing, her loneliness, the ways his neglect has worn her down until “She stares off alone into the night / With the eyes of one who hates for just being born.”

The stories operate in a political landscape – working-class people struggling to make ends meet, financially and morally – against a backdrop of religious language that rarely suggests true belief. And some of them absolutely rut with sex, from I’m On Fire (Born In The USA), through Highway 29 (The Ghost Of Tom Joad) to Reno (Devils & Dust). Bruce really delivers, somewhere between Aretha Franklin’s version of The Night Time Is The Right Time and the kitchen table in James M. Cain’s The Postman Always Rings Twice.

Backstage is sparsely populated: three or four crew, management and the local promoter pad about a brick and concrete corridor wide enough for army manoeuvres. After a few minutes’ wait, at the appointed time, 6pm, Springsteen appears in the dressing-room doorway and waves MOJO in. He’s smiling, with a note of reserve you might almost call English.

The room is bare except for a scattering of his possessions on a large glass-topped table – more papers, a personal stereo, a paperback copy of Songs, a collection of his lyrics and the stories behind his records. There’s a small electric table clock, Woolworths maybe, which faces away from him as he takes a seat. Nothing at all purports to make the place feel “like home”. He sticks one leg straight out on the table and leans back in the black moquette and chrome chair. The seams at the crotch of his jeans are worn white and about to go. He speaks slowly, carefully, pausing often to gather the exact words he’s seeking. An odd aspect of his presence close-up is that he looks average height, average build when standing, and broad to the point of massive when sitting down. Maybe it’s a trick of the blue plaid shirt which, someone says, was a gift from Tom Hanks.

He sits ready, gazing at MOJO with a small frown.

At your Storytellers show (in April 2005), a fan describing herself as “a person of colour” asked how you “managed to capture the minority experience”. You said, “I think it comes from that feeling of being invisible. For the first 16 or 17 years of my life I had that feeling of not being there.” Was that one of the foundations of Born To Run?

Oh, it’s one of the building blocks of all rock’n’roll music. Or blues or jazz. It’s at the core of songwriting and performance and… almost any creative expression. It all comes from a will and a desire to have some impact – to feel your connection to the world and other people and to experience it. To experience your own vitality and your own life force. Go back through any creative expression and you’re trying to pull something out of thin air and make it tangible and visible. That’s why you’re the magician.

But you also told that woman how painful and unpleasant your experience of invisibility was.

Yeah, uh… (hesitates)

It reminded me of the story about you as an eight-year-old boy in Catholic school; you got your Latin wrong and the nun who taught you stood you in the wastebasket because “that’s what you were worth”.

(Laughs hoarsely and heartily) I suppose that was about as symbolic as you could get. So, yeah, the idea of struggling against the wasted life has always been behind my songwriting. And obviously class and race play an enormous part in that here in the United States. If you saw the shock expressed when, during Hurricane Katrina, suddenly all these people who had been marginalised were on television and visible. And people’s shock… was shocking to me. Those people who had been marginalised – who you’re normally seeing on the nightly news in handcuffs being arrested, that’s basically all you ever see of them – suddenly there they are with their kids, their families, and the country reacted with a sad sort of shock, and that’s just part of the history of class and race and it’s a permanent connection to the heart and the birth of blues and jazz and R&B and rock’n’roll music.

That music is one of the tools by which the invisible, the people who were born on the margins, have made themselves visible. It’s crucial and critical to making that kind of music. And I wanted to make a big noise. You want to let people know that you’re here and you’re alive.

Did coming from New Jersey play a part in the sense of being disregarded that fuelled Born To Run?

Maybe the thing that was different back then was I’d never met anybody who’d made an album. You were much further out of the mainstream, particularly before localism in pop music became accepted. I mean, one hour out of New York City and you were in the netherworld. Nobody came to New Jersey looking for bands to sign. That didn’t happen and the sense of being further away from those things was very pronounced.

I did shows in my late teens and early twenties when I was playing to thousands of kids, but nobody really knew about that. We were acting independently of the record business and the concert business; they were just local events. And we were guys who had never been on an airplane until the record company flew us to Los Angeles.

Today I hardly know a band without a CD. The machinery, the technology, to make records was not in your hands. So when I got a record contract I was the only person I had ever known who had been signed, that was the big change, and then we made a couple of records and they didn’t sell that well but still it was miraculous. And then Born To Run came along and… (he breaks off, with a tilt of the head at everything that followed)

In terms of your standing then, something unprecedented happened: you got the covers of Time and Newsweek in the same week (October 1975). But then you seemed to hate it when they came out. Why?

That was the big decision I made. A moment came along when I said, “Gee, I’m not going to do these interviews.” So I wouldn’t have been on those covers. But then I was like, “Why wouldn’t I do that?!” This is my… (halts a rush of words to consider). I had tremendous apprehension and a good deal of ambivalence about success and fame – although it was for something that I had pursued very intensely. But it was: “I’m never gonna know unless I do this.” You know? You’re never gonna know what you’re worth or what your music is worth or what you had to say or what kind of a position you could play in the music community… er, unless you did it. So I said, “Well, this is my shot and I’m gonna take this.”

I was pursuing a cathartic, almost orgasmic experience...

Bruce Springsteen

You were talking about rock’n’roll springing from political and social issues. How was your political consciousness when you recorded Born To Run?

It didn’t exist. That was the last thing in the world that I was…

Even though you grew up in the ’60s?

No, you’re right, I don’t mean it to that degree. In the ’60s, the United States felt more like South America or Central America when I went on the Amnesty tour there [1988, with Sting, Peter Gabriel and Tracy Chapman]. At the press conferences it was all very intense political questions and everybody was involved in these tumultuous events in Argentina and then we played right next to Chile where they’d just gotten Pinochet tottering and so everybody was imbued with political consciousness. In the States in the late ’60s, if you weren’t involved in protesting against the Vietnam War and what the government was doing and the way the culture was changing, people thought there was something wrong with you.

So that was bred into you, and I carried that along with me and at times it came forth and at other times it would recede, I wasn’t particularly aware of it. After the end of the Vietnam War people felt at loose ends and there was a lot of… instability. Look at Born To Run and it would be one of my least political records, certainly on its surface. I was motivated by records that I loved, by the sound I wanted to make and the feeling that I wanted to bring forth. A feeling of enormous exhilaration and aliveness. That was what I was pursuing. A cathartic, almost orgasmic experience.

But then, in 1978, you made Darkness On The Edge Of Town and that “darkness” became a prevailing metaphor in your lyrics.

Mmm. With Born To Run there was a certain degree of your-dream-came-true. You’d found an audience and you’ve had that impact. So it was just part of my nature for better and for worse to go, “Well, what does this mean? What is its personal meaning? What is its political meaning? What does this mean not just to me but to other people?” There’s the concern about the fame, which is interesting because it makes you very present and you have a lot of impact and you have force, but it also separates you and makes you very, uh, singular.

You’re now having an experience that not many other people you know are having. Its irony is that it carries its own type of loneliness. And a whole series of new questions. So I said, for me, really the rest of my work life will be to pursue those answers. Born To Run was a pivotal album in that, after that, my writing took a turn that it might not have in other circumstances. Darkness On The Edge Of Town was an immediate and very natural response to, uh, “How do I stay connected to all these things?”

It was during the Darkness… period that you started your campaign of self-education and particularly studying American history.

Well, Born To Run did have those big themes on it. I was interested in who I was and where I came from, the things I thought gave my music value and meaning, so I pursued that information. Also, I was just naturally inquisitive. High school was just so boring and I never went to college so I missed out on a moment when I may have been – and I say “may have been” – more susceptible to learning things.

So in my mid-twenties I pursued a lot of things that I found inspired me. History inspired me. I guess I was aware of wanting to write about the place where I lived, the people I knew. You wanna get everything you can get out of it and you wanna give all that you can give. You wanna explore the self, you know.

The Grapes Of Wrath became very important to you – the John Ford film, the novel and Woody Guthrie’s Dust Bowl Ballads songs. What got to you about America in the 1930s and 1940s?

A lot of the blessings and the curses were closer to the surface. Look at the movies. From the John Ford film of Grapes Of Wrath, I got that elegiac view of history – warmth, fidelity, duty – the good soldier’s qualities. But film noir came out of those periods too and they were popular films. I think you see that again through the early ’70s, big films like Taxi Driver. People had interest in the undercurrents, the underbelly, an interest in peering behind the veil of what you’re shown every day. There was a sense that there was more than what you are seeing and what was being presented to you, and that was pervasive in the country at large, I think, not just in the progressive elements of society.

I mean, the Vietnam War didn’t end with the hippies being against it or the progressives being against it, it ended when the truck drivers were against it. The ’30s and ’40s, the early ’70s again, those were times when things were in great relief. People were willing to look past society’s mask. That was compelling to me.

Looking past that mask, what did you see?

Just that people were… I do kind of touch on it in some of my early things – Lost In The Flood [from 1973’s Greetings From Asbury Park, N.J]. I was trying to get a feeling for what was actually going on, what were the forces that affected my parents’ lives. I suppose you would have to say it all goes back to your immediate personal experience. Those are the things that shape you. The whole thing of the wasted life, it was very powerful to me.

Did you go on to read political books like the Communist Manifesto?

No, I didn’t read that. But I went through a lot of what was out there it seemed, bits and pieces of a lot of different philosophers. But a book that had an enormous effect on me was America by Henry Steele Commager [and Allan Nevins], a very powerful history of the USA. It went back to that core set of democratic values that the country guided itself by sometimes and sometimes not. It was the first thing I read that made me feel part of a historic continuum – feel our daily participation and collusion in the chain of events. As if this was my historical moment. In the course of your lifetime, how your country steers itself is under your stewardship.

So what did you do? That was an interesting idea to me in terms of how to look at your life, your work and your place. That was very tangible for the first time and it directed some of my writing – along with you want to rock and have fun. You see the effects in Darkness…, The River and Nebraska. It’s certainly in the song Born In The USA; that’s a Vietnam veteran who’s on fire because he’s colliding with the forces of history. But this guy has accepted that personal and historical weight – it’s angry, there’s a social element, there’s a lot less innocence.

With Born In The USA were you deliberately commenting on Reagan’s America – with him in the middle of his first term when you wrote it – or was it post-Vietnam issues that stirred you up, the problems the veterans were having 10 years on?

I was moved a lot by the veterans I’d met. I’d become close to some of them. Vietnam wasn’t written about almost at all until a decade after it stopped – earlier, all I remember is The Deer Hunter and a great Nick Nolte movie which hardly got shown called Who’ll Stop The Rain [both 1978].

But in the early ’80s there was the birth of the Vietnam Veterans Of America. My friend Bob Muller was heading it up and we did a benefit for them on The River tour [1981]. I remember going to see The Deer Hunter with Ron Kovic, who wrote Born On The 4th Of July, and he was looking for things that reflected his experience. The song came out of all that. Bob Muller was the first guy I played it to. That was something.

Apart from reading American literature, you also explored America far more literally by just driving around the country.

Well, I travelled a lot from the time I was 18 or 19. My parents were gone [factory worker Doug and legal secretary Adele moved from Freehold, New Jersey, to California in 1969] and they didn’t have any money to buy me a bus ticket much less an airplane ticket, so I’d drive out to the West Coast maybe once a year to see them. We’d take these big country trips, three or four or five of us – and a dog – jammed into the cab of a truck and you’re driving three days straight without stopping. Just the stuff you did when you were a kid.

As Born To Run’s anniversary approaches, having worked so much on the re-release material, how do you see the album now?

I look back with a lot of amusement on the band at that particular moment, the audacity and insecurity that was all right above the surface. When I came back off The Rising tour [2002] I was excited about the band and I both reflected on the present and took a look in the rear-view mirror, kind of saying, “Where do I go now?” And I’ll tell you what, the finiteness of your experience is real once you’re in your late fifties. This (he gestures at his life, pointing both hands hard at the ground) is finite.

There’s x amount of years left in what we’re doing. I don’t know how many. I hope there’s a lot. I feel like there’s plenty to do, plenty of songs to write, I feel about that the same as I did when I was 24 years old. But part of taking your place in the world is letting that clock tick. Letting that clock tick and being willing to listen to it tick and understand that your mortal self is present and walking alongside of you all the time now.

Meet The New Boss...

This article is taken from MOJO’s brand-new bookazine - MOJO The Collectors’ Series: Bruce Springsteen Essentials. Presenting the definitive guide to Springsteen’s albums, songs, films and books, unearthed interviews, his 50 greatest songs as picked by MOJO’s team of Bruce experts, plus rare and iconic photographs. More info and order your copy HERE!

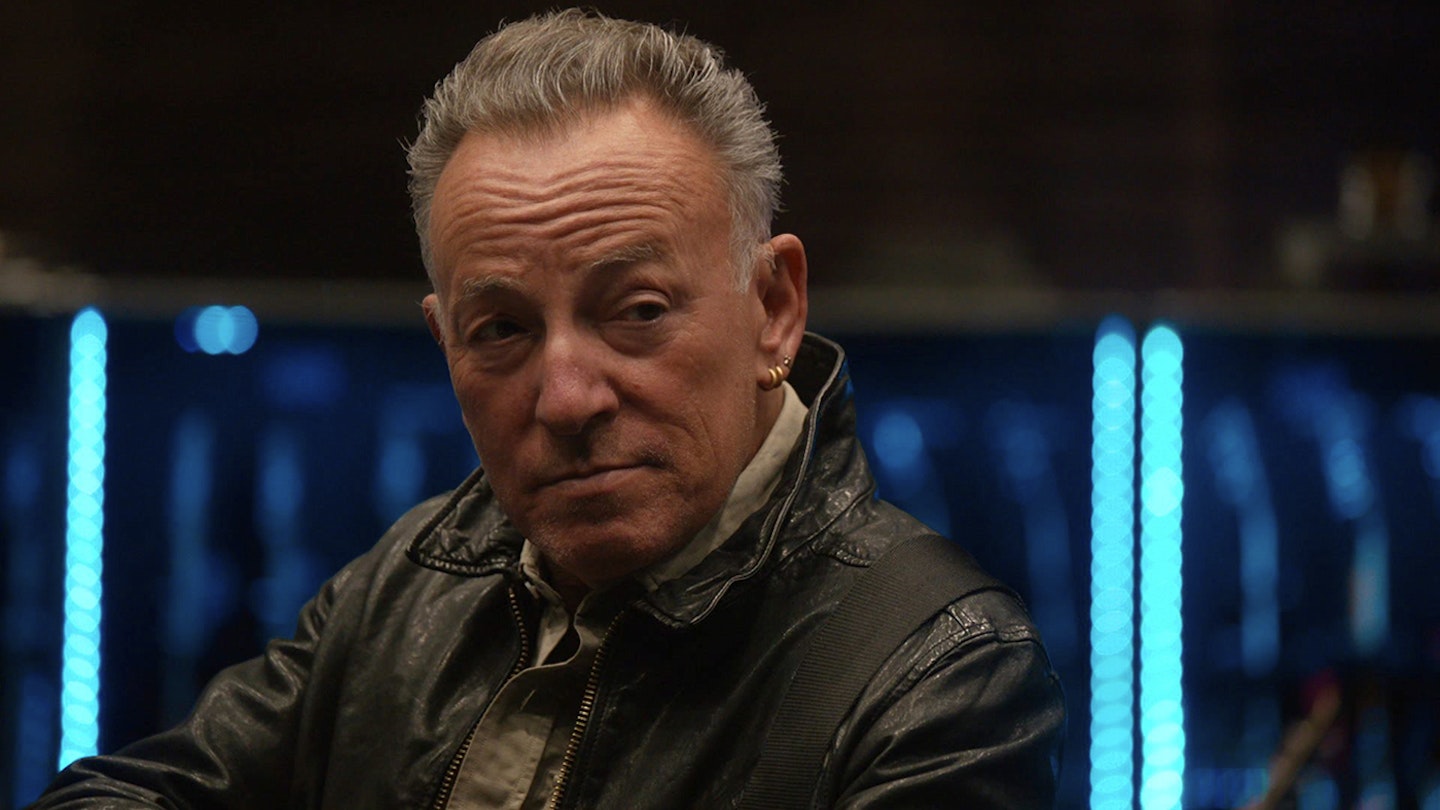

Main picture: Bruce Springsteen in Road Diary: Bruce Springsteen & The E Street Band, directed by Thom Zimny, available to stream on Disney+ now. Read MOJO's review HERE.