THE WHO AS WE KNOW THEM could have been two-hit wonders. Months before December ’65’s debut album My Generation, singer Roger Daltrey was dismissed for beating up drummer Keith Moon. He was soon reinstated, promising pacifism, but violence, resentment and intra-band rivalry would remain at The Who’s heart. And thankfully so, since music as powerful as theirs was unlikely ever to be created in an atmosphere of calm.

Starting life as R&B-playing Mods, they quickly transformed into rule-breaking pioneers, perverting, distorting or ignoring the accepted rock tenets. John Entwistle’s bass and Moon’s drums became lead instruments, vying for attention with Pete Townshend’s guitar, which he’d bash and trash to create an unholy wall of noise, citing Gustav Metzger’s auto-destructive art as inspiration. Daltrey’s role as straight man kept the ship from capsizing – handy considering the group’s early management team of flamboyant visionary Kit Lambert and East End tough-nut Chris Stamp was often as out of control as the group.

“Violence, resentment and intra-band rivalry remained at their heart.”

Contractual and financial problems dogged them throughout their early days, and two years after their debut 45 I Can’t Explain charted, hit singles were drying up. But this was really the start: wowing America at the Monterey Pop festival in June 1967, the group elected to refine and elevate the album as an artform, a path which reached an apotheosis in 1969 with the ‘rock opera’ Tommy. Success as a stadium rock act followed, but Townshend’s impulse to eclipse Tommy led the group into another troubled phase, which saw concept album Lifehouse aborted (it was trimmed into the majestic Who’s Next) and the appearance of their final magnum opus Quadrophenia. The wheels came off in 1978 with Moon’s death, and fallow periods meant virtually no new material until 2006’s Endless Wire, released four years after Entwistle’s death. But their recorded legacy remains vast, deep, and ripe for exploration. Here, MOJO have selected the ten best albums and compilations to head to...

{#h-}

10.

BBC Sessions

BBC/Polydor, 2000

As with The Beatles, The Kinks and others among their 1960s contemporaries, The Who were regularly invited to tape live tracks for BBC radio pop programmes, recording to audiences or ‘as live’ in the studio. Although not as polished as official releases, the Beeb’s engineers and superlative equipment helped to create chunky, alternative recitals of familiar perennials (My Generation, Pictures Of Lily, The Seeker), plus priceless snapshots of the band’s early soul and R&B stage favourites such as Leaving Home and Dancing In The Street. The 26 tracks here end with crunching Old Grey Whistle Test performances of Relay and Long Live Rock from 1973, with an organic magic arguably lacking in the ‘proper’ studio versions.

9.

Endless Wire

Polydor, 2006

Two bandmates gone, Townshend and Daltrey courageously essayed another album as The Who – 24 years after the band’s previous album It’s Hard. The incarnation they revisited was the mid-’70s rock behemoth of Quadrophenia, with tracks such as Black Widow’s Eyes and Mike Post Theme showing Daltrey’s lungs to be intact and that Townshend could still turn his hand to bombast and mighty crash chords. The real surprises were Townshend’s cracked, burnished voice on the Dylan-esque title track, and the mini-concept piece Wire & Glass, a new Lifehouse tributary which saw Townshend’s best songs in decades in We Got A Hit and the elegiac Tea & Theatre.

8.

A Quick One

Track, 1966

The Who’s early years were dominated by the legal wrangling to oust Shel Talmy as producer following My Generation. In late 1966, the group raised much-needed cash by negotiating song publishing deals for Daltrey, Entwistle and Moon, on the understanding that the entire group would come up with material for the subsequent album. Consequently A Quick One took something of a turn for the weird, as three untested songwriters expressed themselves via the creepy and surreal Boris The Spider (Entwistle), Cobwebs And Strange (Moon) and See My Way (Daltrey). But it was inevitably Townshend who stole the show with the baleful So Sad About Us and the magnificent title track’s groundbreaking ‘mini-opera’ of adultery.

"Don't fuck with me, you little shit..." The Who vs Jimi Hendrix, backstage at Monterey.

7.

30 Years Of Maximum R&B

Polydor 1994

Appearing in 1994, this box set remains the most satisfying Who overview, with a judicious collection of 79 studio, live and (then) unreleased tracks, seasoned with tasty snippets of on-stage banter, jingles and TV show dialogue. Beginning with all four High Numbers recordings from 1964, it includes such rare and lost jewels as the group’s cover of The Rolling Stones’ The Last Time (with Townshend on bass) and psychedelic space odyssey Melancholia, a wiggy 1968 outtake. But its genius mainly resides in the way it effortlessly unfolds The Who’s epic journey from R&B-obsessed teenage Mods to the Moon-less, confused rock anachronisms of the 1980s.

6.

Meaty, Beaty, Big & Bouncy

Track, 1971

Though they struggled with the LP format until Tommy, few could deny The Who’s ability to fashion extraordinary, rule-breaking singles. Released in 1971, Meaty… compiled their key 45s so far, and moreover created instant nostalgia for their Pop Art-Mod beginnings, from the ridiculously brilliant bass solo on My Generation to I Can See For Miles’ fierce harmonic intelligence to Magic Bus’s hypnotic hippy shuffle. Unintentionally, it seems as much a concept album as Quadrophenia, charting Townshend’s personal journey from misunderstood teenage outsider (I Can’t Explain, The Kids Are Alright) to twentysomething spiritual adventurer (The Seeker). Perfect in every way.

READ: The Who Record My Generation

5.

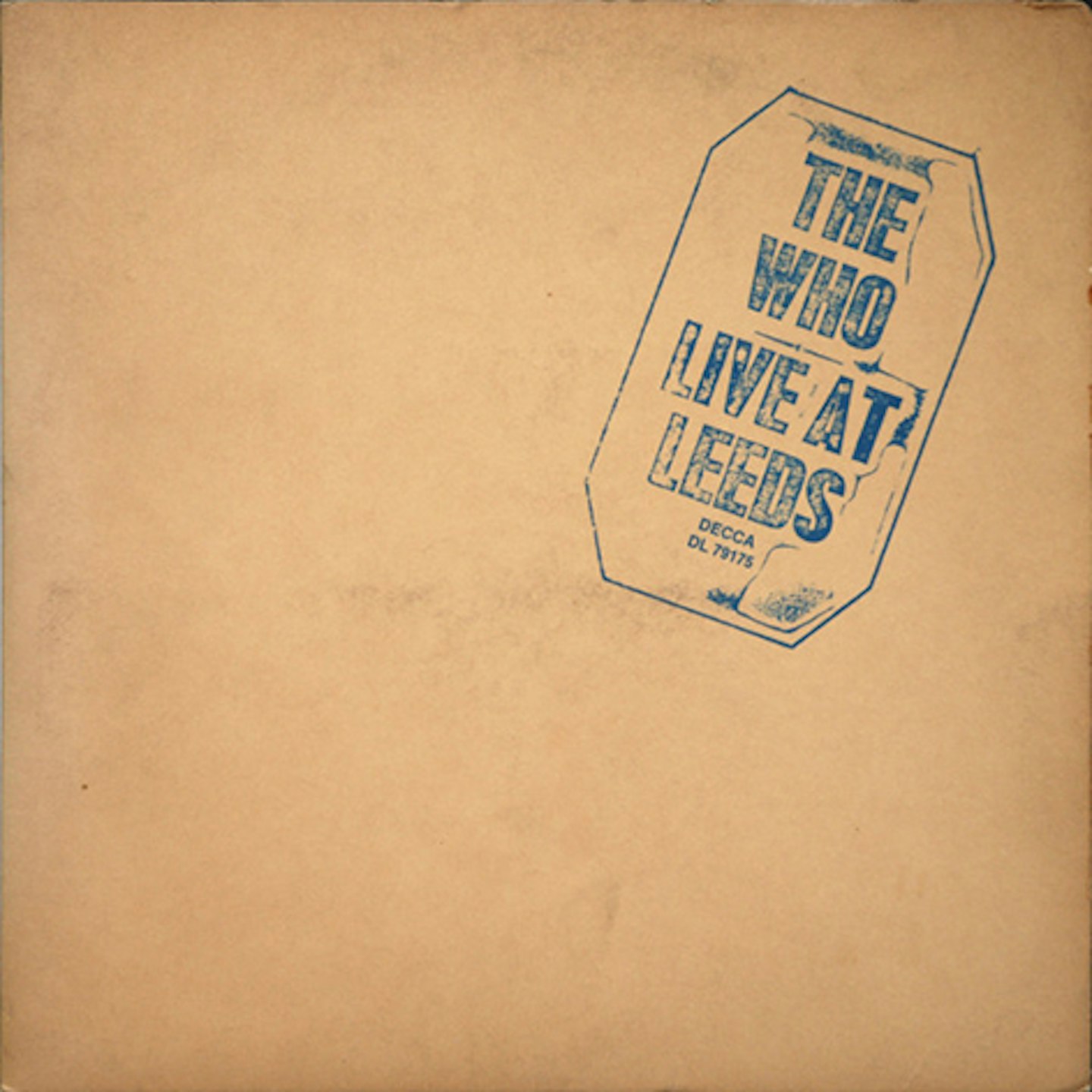

Live At Leeds

Track, 1970

By the time they broke the US market in 1967, The Who were a powerful live act, capable of transcendental performances often capped with gear-smashing finales. The problem was that few of their studio recordings suggested as much. Consequently, after several US tours showcasing Tommy, The Who contrived to capture their thunderous, improv-enhanced live set by taping a February 1970 Leeds University show on the Pye Mobile. Live At Leeds immediately set a lofty benchmark for in-concert rock records – check out the clanging versions of Summertime Blues and Young Man Blues – with subsequent editions adding renditions of Tommy and a spot-the-difference sister date in Hull. Utterly joyful.

4.

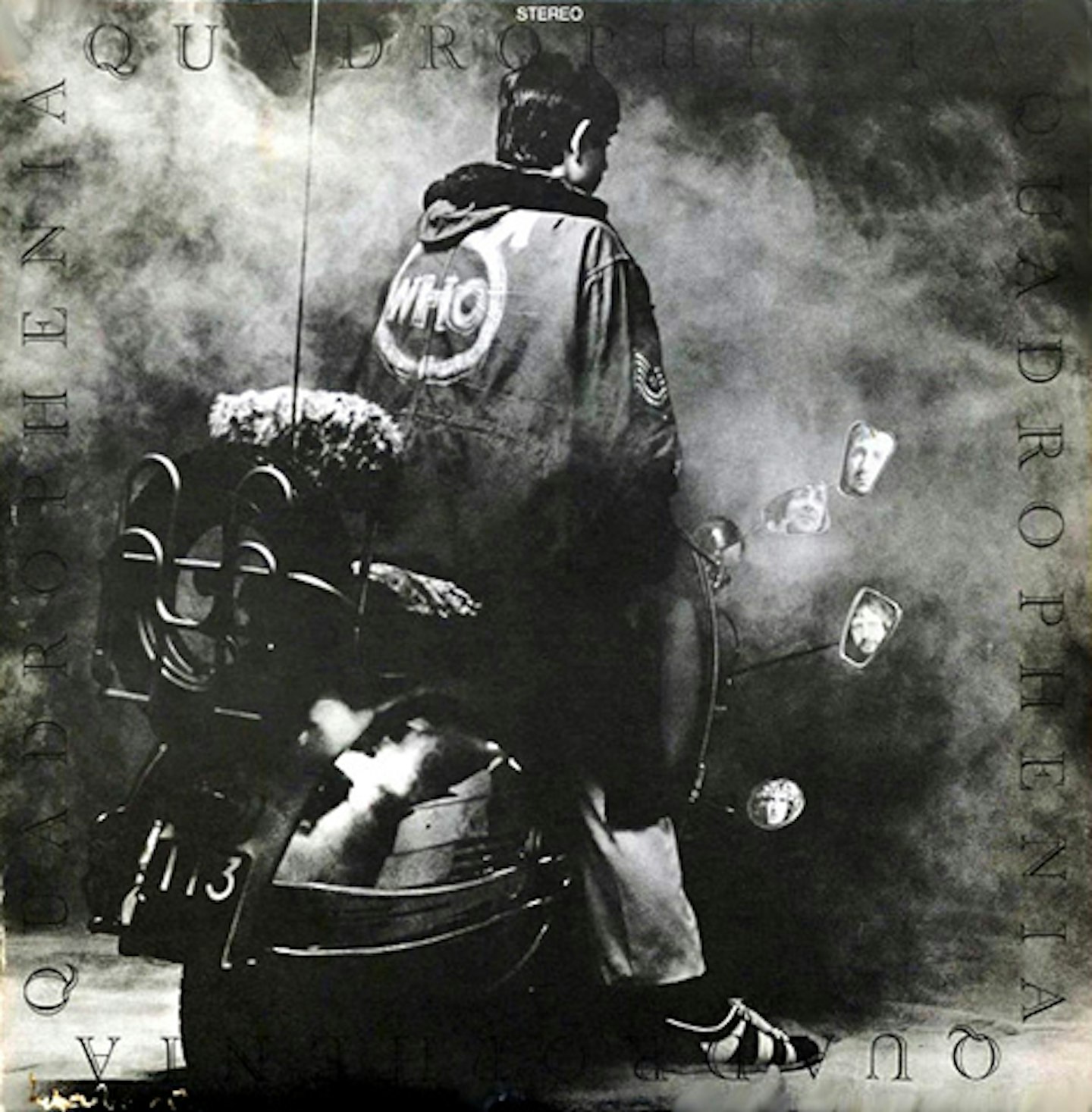

Quadrophenia

Polydor, 1973

Unbowed by the disintegration of Lifehouse, in 1973 Townshend set out to write another, more earthly concept piece. Set in the Mod era, Quadrophenia probed the fractured psyche of troubled pill-popping teenager Jimmy; more, its notion of double schizophrenia enabled a playful examination of The Who’s four-way dynamic, each personality represented by a quasi-operatic leitmotif. Here, music and ideas meshed with breathtaking skill, with every track – from bullish rockers The Real Me and 5:15, through reflective, semi-theatrical fare such as Cut My Hair and the hymnal closer, Love Reign O’er Me – essential to the mood and storyline of the whole. Clever, powerful, overblown, it proved to be The Who’s greatest concept LP.

3.

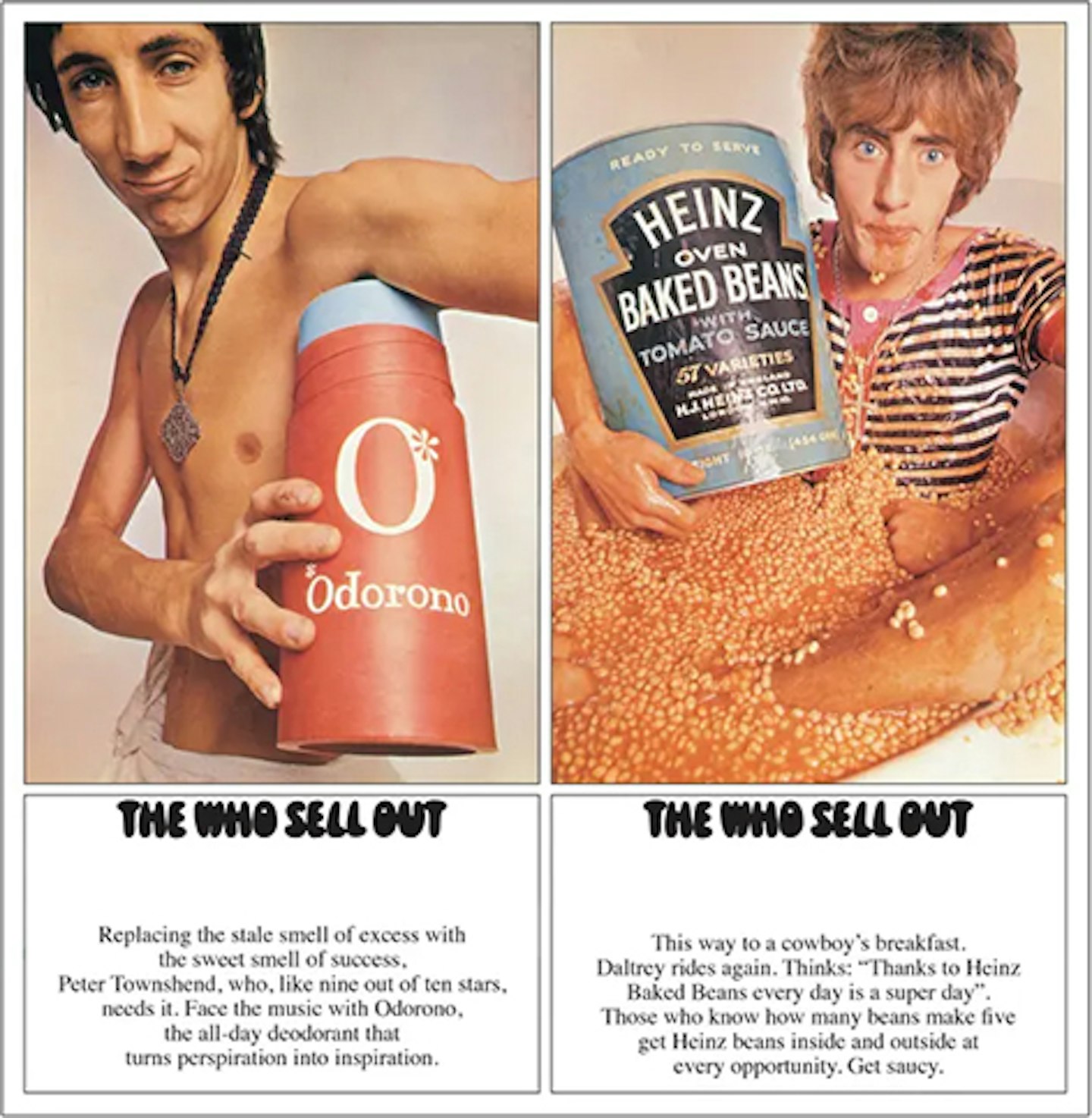

The Who Sell Out

Track 1967

The Summer of Love wrong-footed many acts, and The Who, steeped in street-fightin’ Shepherd’s Bush, found the hippy world difficult to embrace. Stylistically, in 1967 the group were still in an explorative phase, caught in a no-man’s-land between the past (the straight pop of I Can’t Reach You), the present (the quaint folk-psych of Mary Anne With The Shaky Hand) and the future (the powerful, kaleidoscopic I Can See For Miles; the Tommy-predicting story-song Tattoo). Strangely, the overall effect was The Who’s most accessible and undemanding album, melodically rich and full of unexpected twist and turns, all glued together with made-up advertising jingles.

2.

Tommy

Track, 1969

With the assistance of Kit Lambert, throughout 1968 Townshend began sketching what would become the ‘rock opera’ of a deaf, dumb and blind kid who is cured by pinball and becomes a spiritual leader. The concept was rooted in Townshend’s fascination with the teachings of guru Meher Baba, and themes of universal love, all of which crucially chimed with the counterculture generation. The peerless Pinball Wizard, The Acid Queen, I’m Free and See Me Feel Me injected a new vector into rock music, exploring psychic elevation and personal redemption; rock grew-up in one fell swoop, and Pete Townshend obsessively strove for years to come to find another concept as powerful. And with Ken Russell’s film of the LP, rock movies moved into a new era.

Pete Townshend interviewed: The Who guitarist on his Lifehouse ‘plans’, Pearl Jam's Eddie Vedder, neotericism, ‘telematics’ and more!

1.

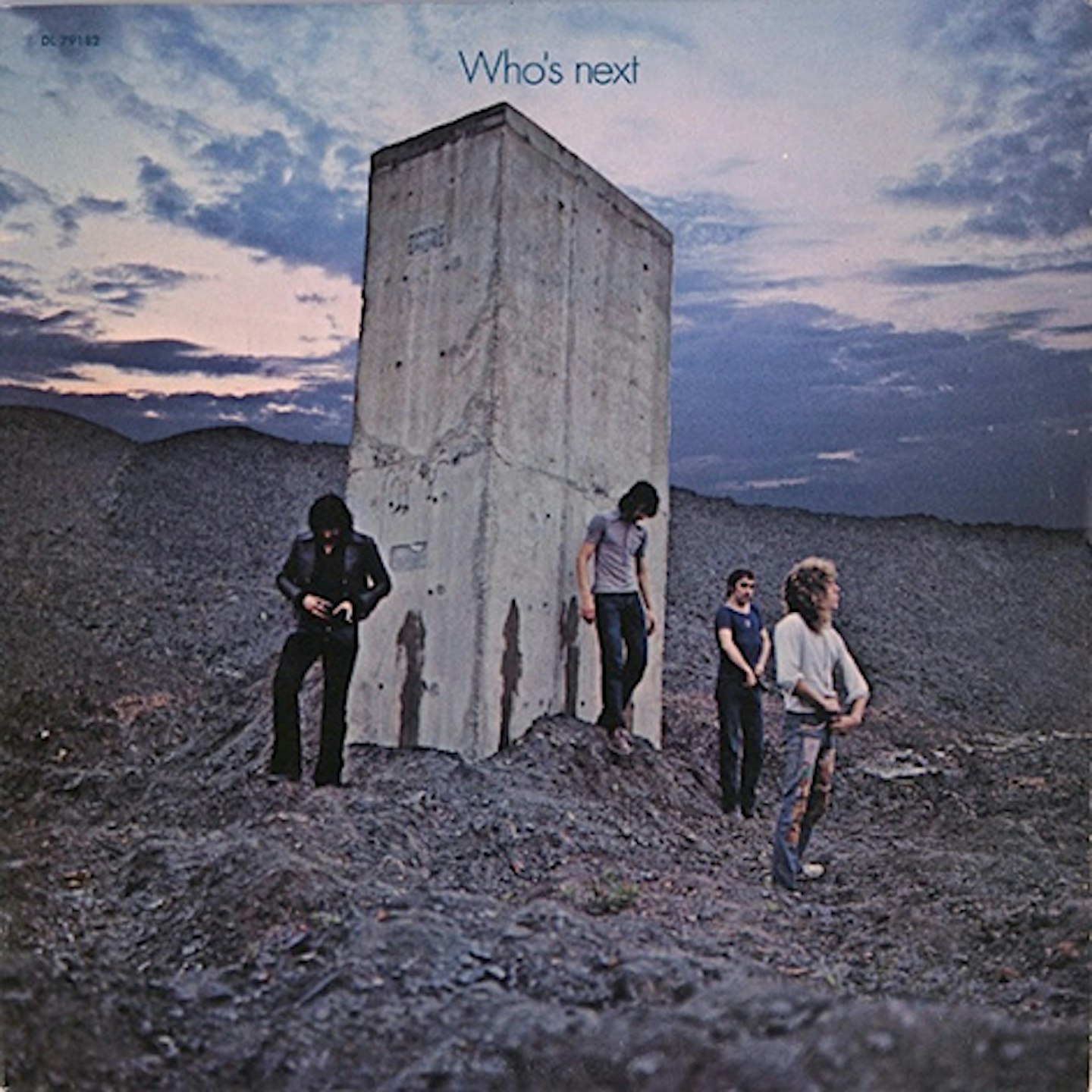

Who’s Next

Track, 1971

It was originally conceived as Lifehouse, a project that came to baffle Townshend’s bandmates with its sci-fi and quasi-religious elements including “experience suits”, a proto-internet set-up called The Grid, a single note binding all beings. Abandoned amid larger worries about Lambert and Stamp’s growing drug problems, producer Glyn Johns was drafted in to rescue the project, taking the strongest songs and shaping them into one of the roughest, meanest rock albums ever made, from the synth-skittering Baba O’Riley and politico sledgehammer Won’t Get Fooled Again, to the sunny Going Mobile and haunting Behind Blue Eyes. Townshend’s dented price was rock’s gain.