Various

Why Don’t You Smile Now: Lou Reed At Pickwick Records 1964-1965

★★★★

LIGHT IN THE ATTIC

In the fall of 1964, Lou Reed was as far from the action in that wild, crucial pop year – the British Invasion, Bob Dylan’s rise to godhead, the soul explosions at Stax and Motown – as an aspiring provocateur could get and still be in the music business. Fresh out of Syracuse University with a BA in English and a minor vinyl resumé – a 1958 single with his teenage vocal group, The Jades – the Brooklyn-born singer and songwriter, then 22, was on the assembly line at Pickwick International, a label-and-studio sweatshop in Long Island City specialising in pastiches of the day’s hits for quickie 45s and budget-rack compilations with passé beatnik titles like Out Of Sight! and Soundsville!.

-

READ MORE: Lou Reed Interviewed: “I’m a guitar player who likes feedback, I’m not that complicated!”

It was, in Reed’s own words, “a real hack job,” the 9-to-5 dark night before his revolutionary dawn with The Velvet Underground. Mentored at Syracuse by the poet Delmore Schwartz and charged by the transgressive novels of William Burroughs and Hubert Selby, Jr., Reed had bigger ideas: “To knock the door down on what rock’n’roll songs were,” as he once put it to me. “Drugs, violence, New York, all this stuff.” In fact, while at Pickwick, Reed was quietly making demos of the Velvets’ future songbook: Heroin, Pale Blue Eyes, I’m Waiting For The Man.

But on the company’s clock, “I was an unsuccessful Ellie Greenwich, a poor man’s Carole King,” churning out surf, R&B and girl-group knockoffs with fellow staffers Terry Philips, Jerry Vance and Jimmie Sims. Reed sang and played on some records as well, low-brow productions for footnote acts (Jeannie Larimore, Robertha Williams) and made-up bands: The Primitives, The Surfsiders, The Beachnuts. The general verdict, as that ephemera creeped out on Velvets bootlegs and collectors drove up the prices of original pressings, was summed up by VU scholars M.C. Kostek and Phil Milstein in their pioneering fanzine What Goes On: “No work Lou has done is so trivial, so pre-fabricated, so tossed-off.”

Except when it wasn’t. The latest instalment in Light In The Attic’s Lou Reed Archive Series, Why Don’t You Smile Now is the first, official account of the artist’s brief spell as a paycheque composer and sideman: 25 tracks of faux-Brill Building candy, corn and echo-laden chaos with linernotes by Richie Unterberger worthy of a PhD thesis. It is also an essential, at times wickedly delightful‚ corrective to the habitual dismissals of this era, Reed’s included. The Pickwick gig was, in fact, “a dream job”, Lenny Kaye asserts in his introduction to the set. Reed was “trying on persona, style, songs as if they were clothes” while honing “the restless and relentless work ethic that drove him ever forward.”

Later, in and after the Velvets, Reed routinely cited his favourite 1950s voices and the bonfire records at the heart of his craft: Dion, doo wop icon Nolan Strong and Bronx angels The Chantels; raw Sun rockabilly and the free jazz of Ornette Coleman. That spiritual jukebox is in constant rotation here as Reed leaves his evolving mark on You’re Driving Me Insane, a Soundsville! burner supposedly by The Roughnecks that sounds like a dry run for the Velvets’ rave-up sections in Heroin; The Hi-Lifes’ Soul City, an early hard-driving spin on the party and salvation that Reed delivered with more flair and polish in Loaded’s Rock & Roll; and Oh No Don’t Do It, a plaintive ’64 gem by the female singer Ronnie Dickerson that Reed could have easily slipped onto Coney Island Baby.

Reed landed at Pickwick via Syracuse; the girlfriend of the manager of Reed’s college band recommended him to Terry Philips, a Pickwick artist (his three tracks here are malt-shop love in the key of Gene Pitney) and the head of that writers’ room. “We wrote 33 songs and sang, played and recorded them in two days,” Reed boasted in a letter to Delmore Schwartz a few months into the job, an expediency made all too plain across this miscellany. Cycle Annie by The Beachnuts is a noisy takedown of Jan & Dean hot-rod pop with Reed up front, drawling across the beat like a talking-blues Dylan. Teardrop In The Sand by The Hollywoods is barely arranged, a skeletal rhythm track under a bizarre vocal mash-up of Frankie Valli and The Shangri-Las.

Then there’s The Primitives’ late-’64 single The Ostrich, the most notorious of Reed’s Pickwick artefacts and the improbable spark for his next act. That November, New York fashion columnist Eugenia Sheppard reported that ostrich feathers were all the rage in Paris, inspiring Reed to invent a new dance craze that, in one verse, included stepping on one’s own head. Rushed out the same month, The Ostrich remains an astonishing bedlam. Reed’s hectoring vocal and the brittle minimalism of his guitar (he tuned each string to the same note) are so overrun with deep-sea reverb and frat-party yelling that The Premiers’ classic ’64 racket Farmer John is hi-fi-snob nirvana in comparison.

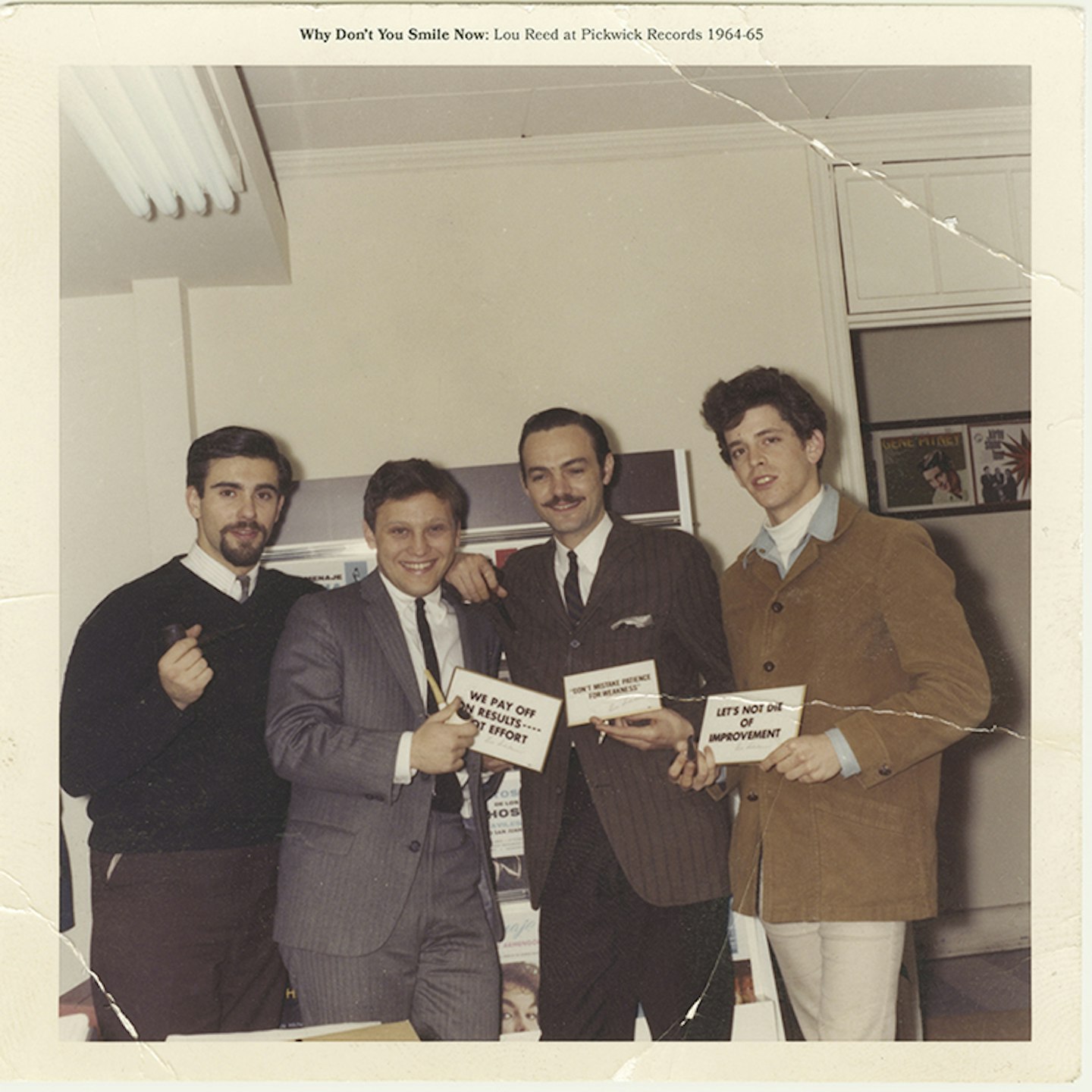

Incredibly, Reed and Philips tried to promote the single with a touring Primitives, hiring two hip-looking guys Philips met at a party: Welsh composer John Cale and experimental artist Tony Conrad along with their friend, sculptor Walter De Maria, on drums. The band folded after a few shows but Cale stuck around, intrigued by Reed’s other body of tunes and earning a co-writing credit on this album’s title track – actually recorded by a real band, the All Night Workers (more Reed pals from Syracuse), and maybe the most Velvets-like moment here with its trance-guitar chord progression and circular chant-like hook. By the summer of 1965, Reed, Cale and guitarist Sterling Morrison were becoming The Velvet Underground.

Sixty years later, Why Don’t You Smile Now definitively addresses and illuminates the weirdest part of that origin story. Nothing here is genius. But much of it is revealing – the hard labour that has to come before legend – and a lot of it is just ragged fun, like a one-man Nuggets from the end of an innocence. “The other guys, I think, wanted to have a future making pop records,” Reed told me in ’86. “Meanwhile, I had my own songs I was writing. And they ended up on the first Velvet Underground album.” This is the best of the madness and minutiae that happened along the way. Dig in with a smile.

Why Don’t You Smile Now: Lou Reed At Pickwick Records 1964-1965 is out now on Light In The Attic.

LISTEN/BUY: Spotify | Apple Music | Amazon | Rough Trade

Main picture: The Primitives, 1965: (from left) Tony Conrad, Walter De Maria, Lou Reed, John Cale. Courtesy of Tyler Hubby.

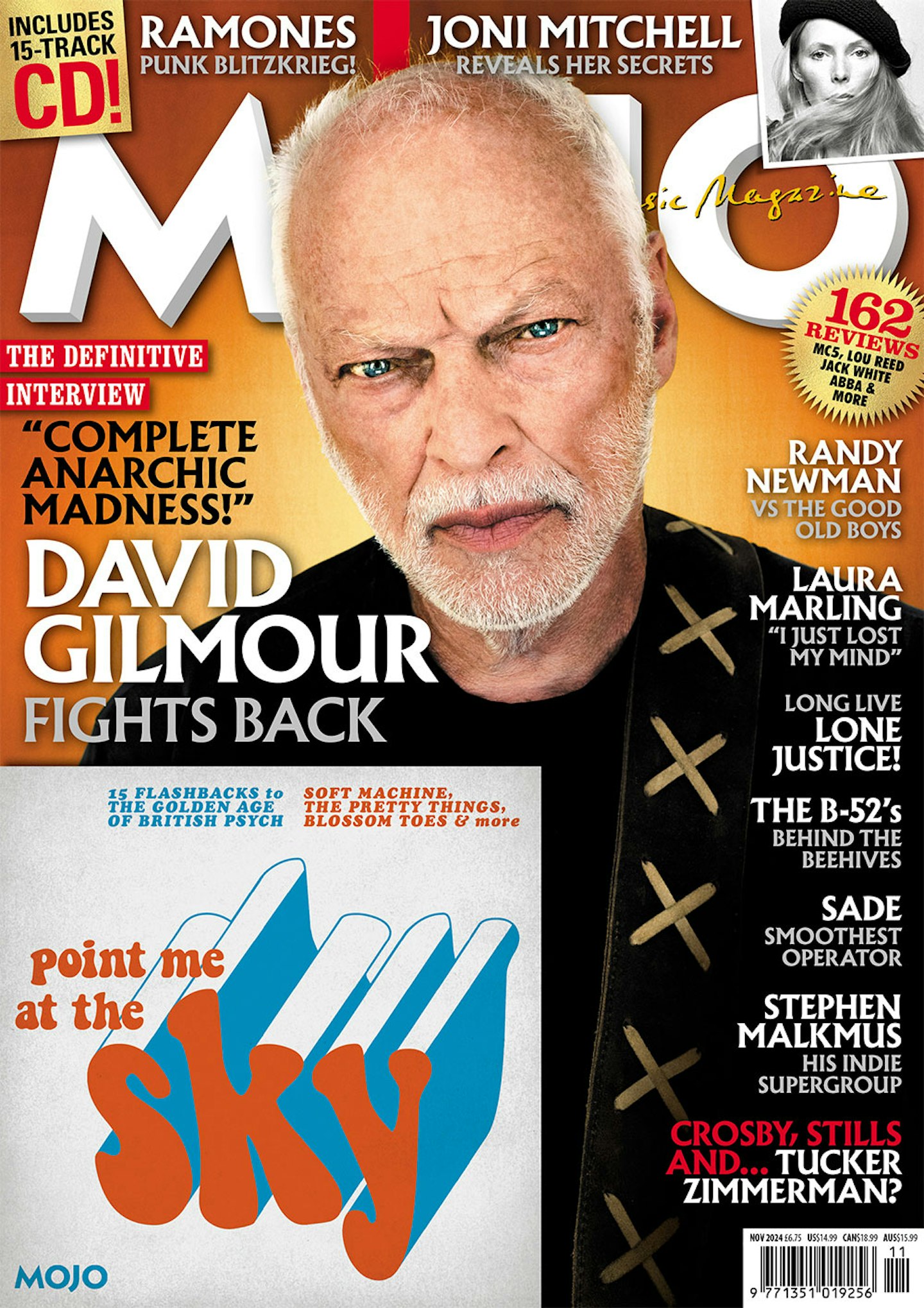

Get the latest issue of MOJO for the definitive verdict on all the month’s best new releases, reissues, music books, films and more. More info and to order a copy HERE!