Describing the beginning of Highway 61 Revisited’s opening salvo, Like A Rolling Stone, Bruce Springsteen ventured “that snare shot sounded like somebody had kicked open the door to your mind”. Dylan contemporary Phil Ochs said of the album, “It’s impossibly good… how can a human mind do this?” Hyperbole aside, Highway 61 Revisited remains one of rock’n’roll’s sacred texts, widely regarded as the base metal from which all subsequent poetic, transcendent rock music has been wrought.

-

READ MORE: Bob Dylan’s 60 Greatest Songs – As picked by Paul McCartney, Nick cave, Patti Smith and more…

With its intoxicating swirl of beat poet hip and biblical allegory, visceral rock’n’roll and cerebral balladry, contemporary wit and old weird America, the album captures a 24-year-old Bob Dylan at the moment of his ascension from needle-sharp folk provocateur to visionary rock deity. It’s an album that simultaneously looks backwards and gallops forwards, dragging popular music into the modern age with it.

Dylan had shunned political folk songs on 1964’s Another Side Of Bob Dylan, and gone even further on the subsequent Bringing It All Back Home by adding electric instruments and Symbolist poetry-inspired lyrics, much to the disdain of Greenwich Village’s puritanical folk intelligentsia. Dylan was consciously stepping into the pop spotlight, but he was taking his literate songwriting with him. If this was pop, it was some way from the sunny love songs still favoured by The Beatles. Indeed, with the August 1965 release of Highway 61 Revisited the competition suddenly began to look distinctly frivolous.

The album was recorded at Columbia’s Studio A in New York, initially with Bringing It All Back Home producer Tom Wilson at the controls, later replaced by Bob Johnston. Many of the musicians who had graced its predecessor were recalled, including bassist Harvey Brooks, pianist Paul Griffin and drummer Bobby Gregg. Key additions were Paul Butterfield Blues Band guitarist Mike Bloomfield and session man Al Kooper, who turned up simply to watch before joining in on Hammond organ – an instrument he’d never touched before.

-

READ MORE: Bob Dylan In The 60s: All The Albums Ranked

Early sessions issued a landmark: Like A Rolling Stone. Musically it may have stolen from Richie Valens’ La Bamba, but lyrically it came from an entirely different universe. A raging, vituperative epic whose venom-spitting lyrics were edited down from pages of what Dylan dubbed “vomitifc” scrawling, its rhetorical chorus (“How does it feel/To be without a home/With no direction home/Like a rolling stone?”) made an anthem of existential angst. The song chimed with the album’s overarching sense of restlessness, substituting logical narratives for surreal juxtapositions, sardonic put-downs and elliptical symbols. In June, Like A Rolling Stone was released as a single, racing to Number 2 on the US chart where it threatened to dislodge Sonny & Cher’s I Got You Babe.

Work continued after July’s Newport Folk Festival at which a leather-jacketed Dylan had fronted the all-electric Butterfield Blues Band, deepening the gulf between him and the folk caucus still further. Emboldened, Dylan and collaborators cut the remainder of Highway 61 Revisited in a whirlwind six days at the beginning of August.

If Like A Rolling Stone signposted Dylan’s conversion to unfettered rock’n’roll, then the amped-up, meta-rockability of tracks such as Tombstone Blues and From A Buick 6 confirmed it in spades, Bloomfield’s wild lead guitar punctuating Dylan’s hipster delivery like a sparkling knife blade. Contrast came by way of Queen Jane Approximately’s stately folk rock – rippling cascades of piano and organ offsetting Dylan’s yearning opaque lyrics.

The ennui of It Takes A Lot To Laugh, It Takes A Train To Cry owes something to the tradition of Dylan heroes Hank Williams and Jimmie Rodgers. Part weary lament, part swaggering country blues, it manages to seem both earthy and esoteric. Ballad Of A Thin Man, led by Dylan at the piano, is musically more sophisticated. An elegantly jazzy ballad, it’s another of Dylan’s withering put-downs – his wounding, anti-critic barbs simultaneously hymning the generation gap: “You know something is happening/But you don’t know what it is/Do you, Mr Jones?”

The album’s title track transplants the biblical story of Abraham and Isaac to the Midwest. Highway 61 runs from Louisiana right up to Dylan’s hometown Duluth, Minnesota and on to the Canadian border. Between the wars it was a major artery taking African Americans – and with them the blues – north in search of industrial employment. It serves Dylan as a resonant metaphor for his own migration from folk piety to electric provocateur and beyond.

Just Like Tom Thumb’s Blues finds Dylan in stoned, road-weary limbo, initially lost south of the Mexican border, then ranging over the landscape from “Rue Morgue Avenue” to “Housing Project Hill”, before heading “back to New York City”. He drops drug references along the way (“I started off on burgundy/But soon hit the harder stuff”), while the band turn a slow 12-bar blues into a thing of heavy-lidded beauty.

On the closing Desolation Row the electricity abates. As if cocking a snook at the naysayers, Dylan returns to the folk form, ably abetted by West Virginian Charlie McCoy’s liquid guitar runs, saving his most outlandish lyrics for this 11-minute digression peopled by an exotic cast of heroic grotesques, from Cain and Abel to Ezra Pound and T.S. Eliot. Desolation Row remains one of Dylan’s signature works, an epic of moral bankruptcy; an apocalyptic troubadour ballad as imagined by surrealistic filmmaker Luis Buñuel.

Dylan would move on again with the following year’s Blonde On Blonde, but by then the folk rock floodgates would be open and his groundbreaking days numbered. It’s easy to overlook just how fast Bob Dylan was moving in the mid-’60s; luckily he lingered long enough to commit Highway 61 Revisited to posterity.

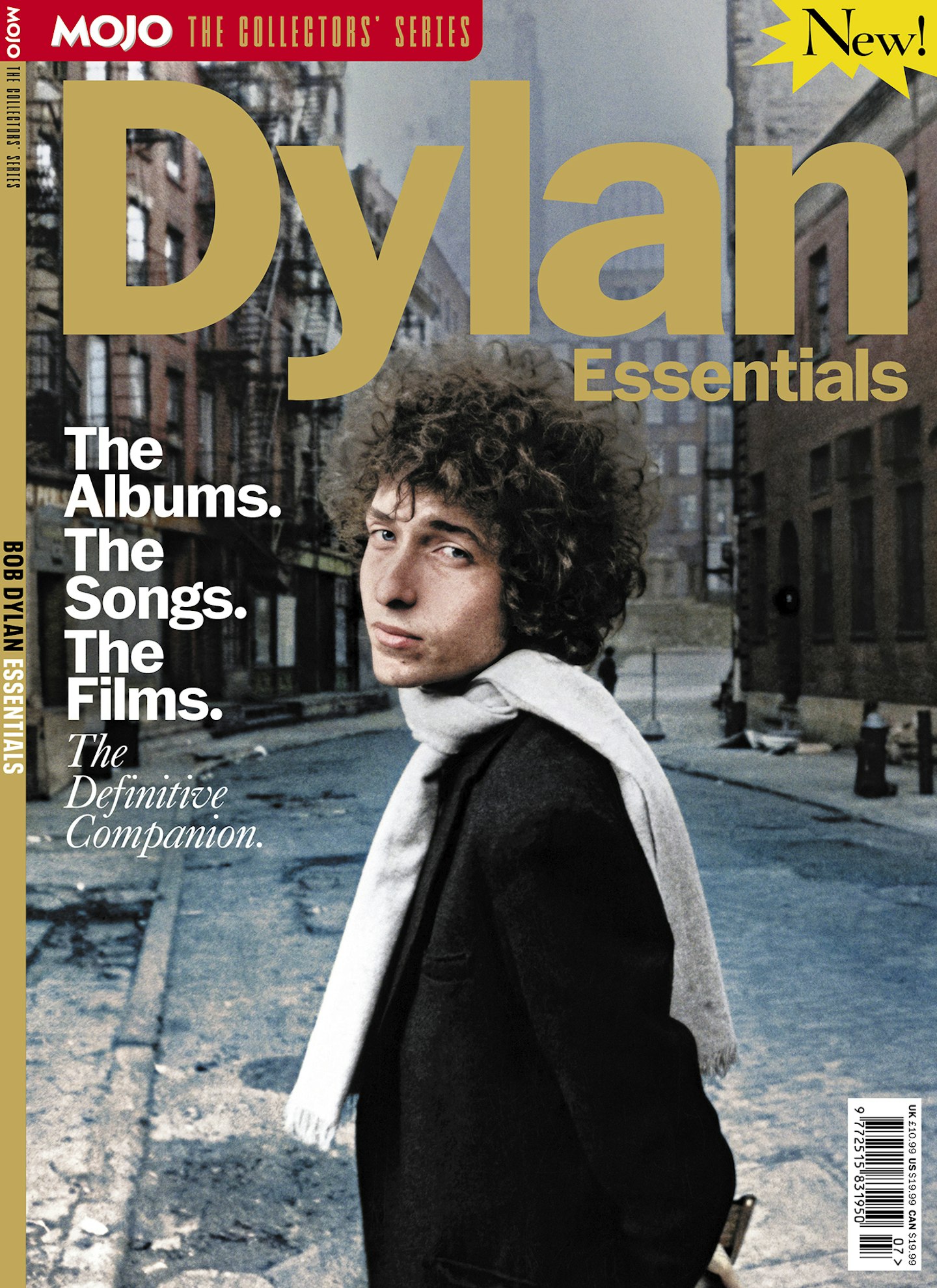

This article originally appeared in MOJO The Collectors Series: Bob Dylan Essentials. Keep an eye on mojo4music.com for news of our next deluxe, special edition bookazine.