When Peter Green named his band Fleetwood Mac back in 1967, no one knew quite how far-seeing his decision would be. The idea was to honour the talents of the group’s rhythm section, drummer Mick Fleetwood and bassist John McVie, who would reward Green’s largesse by remaining the only constant band members throughout the next five decades of Fleetwood Mac’s tempestuous and ever-entertaining history.

Green’s incarnation of the group is still discussed in hushed, reverential tones by fans of the British blues boom of the late ’60s, though it was the guitarist’s acid-induced breakdown in 1970 that grabbed headlines: seeking a more spiritual path, he resolved to give away all his money and encouraged his band members to do the same. His departure from the group soon afterwards marked the beginning of years of mental turmoil for the star, while his old band soldiered on with a shifting line-up and dwindling sales.

But then 50 years ago, in 1975, came the arrival of Lindsey Buckingham and Stevie Nicks, and the transformation of Fleetwood Mac’s fortunes. Their first album together, simply called Fleetwood Mac, sold several million copies, though it’s the follow-up, 1977’s Rumours, that has most enchanted and intrigued music fans ever since. During its gestation, the two couples in the band – Christine/John and Stevie/Lindsey – split up in explosive circumstances, and the drama fed into timeless songs such as Dreams, Don’t Stop and Go Your Own Way.

The drama didn’t stop there, of course. From thereon Mac’s story has been one of emotional departures, dismissals and reunions – with some fabulous music to soundtrack them. The band may have become defunct since Christine McVie’s sad passing in 2022, but one imagines that the bullet-proof rhythm section will be Fleetwood Mac forever.

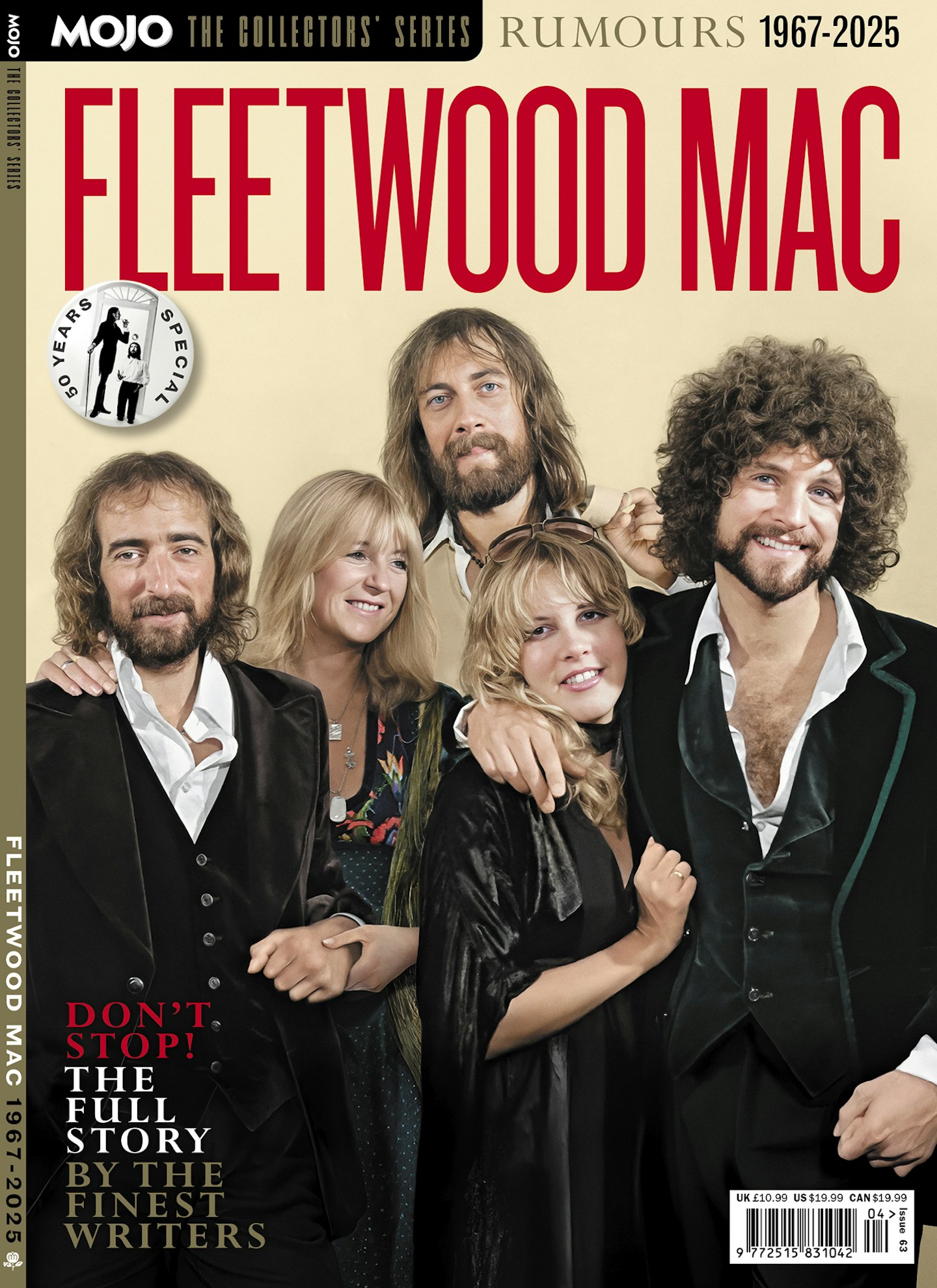

In shops now and available to order HERE, MOJO The Collectors’ Series: Fleetwood Mac Rumours 1967-2025 presents the finest writing on the band and their barely-believable story in one deluxe bookazine. Featuring in-depth features and exclusive interviews with Stevie Nicks, Lindsey Buckingham, Mick Fleetwood, John McVie, and fallen Mac members Christine McVie and Peter Green, it traces the turbulent majesty of rock and roll’s greatest soap opera and celebrates the music the various iterations of Fleetwood Mac have made together over the years. In this extract, we offer a taste of MOJO’s expert selection of the band’s greatest ever songs…

30.

Tango In The Night

(from Tango In The Night, 1987)

Unashamedly mainstream and blatantly bonkers.

With the others indisposed, Christine McVie (subtly) and Buckingham (not so subtly) took control of Tango In The Night, and no more thrillingly than on the unfettered title track. Originally scheduled for a Buckingham solo project, but something of a template for the Buckingham/McVie collaboration of 2017, this was the swaggering offspring of Tusk’s title track: giant drums; McVie wailing appealingly; a blistering guitar solo all the better for its sheer inappropriateness, and what sounds like harp and castanets. JA

29.

Landslide

(from Fleetwood Mac, 1975)

From Stevie and Lindsey’s lowest ebb, a ray of hope.

1974. Lindsey Buckingham is on a demoralising tour backing Don Everly, leaving Stevie Nicks in Aspen, Colorado. After another day’s waitressing, she considers their poverty, their future, their fracturing relationship – and ponders quitting music. Instead, she writes this song, as a redoubling of intent. Within three months, they’re invited to join Fleetwood Mac, and she’s sung Landslide at almost every concert she’s played since. “Landslide’s dear to Lindsey and I,” she says later, “because it’s about us.” Isn’t that what they’re all about? SC

28.

Show-biz Blues

(from Then Play On, 1969)

Green inherits the absent Spencer’s bottleneck and makes it sing.

The post-’67 backlash against pop glitz and psych shimmer was exemplified by the Mac, who dressed like tramps and were keen to state their everyman qualities in song. Here, Peter Green stops time with his 20-second slide intro before revving into the body of this touring muso’s complaint, Fleetwood’s tambourine riding shotgun. The lyric – especially “You’re sitting there so green / Believe me, man, I’m just the same as you” – presages his soon-to-be more jaundiced, perhaps psychotic, takes on fame and wealth. DE

27.

Never Going Back Again

(from Rumours, 1977)

A little folk song holds its own.

At root Buckingham giving solo mode a dry-run, the finished Never Going Back Again dispensed with Fleetwood’s early brushes-work, leaving a pretty exoskeleton of taut, Travis-picked guitars. Buckingham’s vocals (even the massed “mmms” are all him) channel an economical lyric full of resolve, the song reportedly inspired by an on-the-road dalliance while on the rebound from Stevie. A courtly little dance made from love’s missteps, it was Rumours’ daintiest moment. JMcN

26.

Songbird

(from Rumours, 1977)

Christine’s shiversome solo turn.

Rumours’ co-producer Ken Caillat heard Christine McVie rehearsing this song one night and suggested they capture it in one of the auditoria at UC Berkeley, settling on the Zellerbach Hall Auditorium. McVie sang and played the song alone on-stage in the empty hall, a dozen red roses on top of her piano. She has described Songbird as: “a little prayer… an anthem for everybody.” For 21 years, from its release until McVie left the band, it closed every Fleetwood Mac show. JI

25.

Love That Burns

(from Mr. Wonderful, 1968)

Ghosts blown in from the Windy City’s sad side.

First thing you hear is the room, aged walls of heartache and thick, energy-sapping air muting and distorting every sound. Then dig the slowness, for this is Green’s riposte to the volume and velocity of “progressive blues” – voice muffled in defeat, tired, brilliant fingers bending and sustaining notes. It’s the blues boom’s anguished equal to Janis Joplin’s Ball And Chain. But when Green answers Christine Perfect’s piano play-out with the most consoling chording of all time, know that restraint is the victor. MP

24.

Sara (3/10/79)

(from Tusk – Deluxe Version, 2015)

Nicks’s most mythos-laden track, the longer the better.

Nicks wrote Sara – named for Sara Recor, her friend who married Fleetwood after his affair with Stevie, or her aborted baby with Don Henley, or her alter ego, or all three – as a 16-minute piano epic. This 8:48 outtake version invokes her pre-fame penury as a cleaning lady, wrestles with the ghosts of lovers lost and paths not taken, struggling to honour “the poet in my heart”. The 6:22 version on the original Tusk, and the 4:41 single edit are, by comparison, acts of sacrilege. SC

23.

Closing My Eyes

(From Then Play On, 1969)

Green is the colour of spiritual wilderness.

With the success of Albatross, and Mac’s growing interest in the US market, came loud accusations of “Sell out!” Yet no one grappled more with their conscience in spring ’69 than Peter Green, whose Closing My Eyes was a rock opera in microcosm, a one-man pilgrimage into the soul, lit with siren-like Spanish guitar and portentous tympani. There’s no blues wailing here, just a lonesome lament set against dolorous guitars, Green’s lovesickness seemingly less for the girl than for God. MP

22.

Little Lies

(from Tango In The Night, 1987)

Of course, he’s lying.

Big-haired, soft-focused and digitally buffed, there’s desolation in this ambient pop-rock ballad’s breathy choral filigrees. Written by Christine and new husband Eddy Quintela, its narrator longs to defer the terminal car crash of the dysfunctional love affair for one more day, but seems guiltily aware of the sweet, masochistic kick of being deceived (those lies could easily be ‘lines’ – does that explain the knowing tone of backing vocalists Nicks and Buckingham?). IH

19.

Gypsy

(from Mirage, 1982)

Nicks pines for pre-Mac simplicity.

From the undervalued Mirage, Gypsy, with its classic Fleetwood thwack, chiming Buckingham guitar hook, misty multiple backing vocals, ascending melody and lyrical theme, adds up to the quintessential Stevie Nicks song: unorthodox yet madly hooky, immediate yet elusive. As Nicks’s songs often do, it just kind of glides by, leaving the listener wondering what they just witnessed. Buckingham’s double-speed steel guitar solo, pealing into the distance, signifies the Gypsy moving on again, “back to the velvet underground”. JI

18.

Shake Your Moneymaker

(from Peter Green’s Fleetwood Mac,1968)

With Jeremy Spencer in the driving seat, bottlenecks expected.

Their debut album’s rampage through Elmore James’s 1961 12-bar blues-boogie classic flung Jeremy Spencer’s bottleneck to the fore. Kicked off by Green’s guitar in the role of the original’s piano, Spencer’s slide and vocal quickly take over, as McVie’s bass urges over the driving pulse of Fleetwood’s drums. Fast and insistent, the track represented the second wave of ’60s British blues interpreters hitting an unrestrained stride, Spencer’s shouts and yelps demanding moneymaker (aka butt, booty) be shook. GB

17.

Big Love

(from Tango In The Night, 1987)

An angsty masterpiece bristling with oddball pop hooks.

One of three songs Lindsey Buckingham donated from his intended third solo album to what would become Tango In The Night, Big Love showcases his combination of twitchy angst and pop catchiness – a synth part on the demo even evokes Hot Butter’s hit Popcorn. A Beach Boys devotee, Buckingham here sounds inspired by Depeche Mode’s Vince Clarke – until the guitar solo screams in support of his lonely, bitter anguish. Contrary to rumour, the boudoir “ahhhs” were a heavily EQ’ed Buckingham and not the lifestyle-impeded Nicks. MS

16.

Tell Me All The Things You Do

(from Kiln House, 1970)

Interregnum boogie from the Mac’s Lost Boy.

Peter Green was lost to LSD and Jeremy Spencer wanted to play rock’n’roll homages. Luckily, 20-year-old guitar firebrand Danny Kirwan had ambitions to keep the dream alive. One was this flanging, choogling rocker with one eye on the bar and the other on the far horizon, stinging like an English Creedence as Kirwan riffs, thrusts and croons an economy omni-mantra of total openness. Sadly, it’s over too soon, not unlike Kirwan’s own troubled, fulgent career. IH

15.

Say You Love Me

(from Fleetwood Mac, 1975)

Christine McVie smashes through the glass ceiling.

On the one hand, Buckingham and Nicks’s arrival in Fleetwood Mac took songwriting pressure off Christine McVie. On the other, the pair were so obviously more skilled, pop-wise, than the departed Bob Welch, she had to up her game. And she did: writing three of Fleetwood Mac’s four singles. This sexually charged tale of willing surrender (not, you suspect, a tale of willing surrender to John McVie) was the pick, and so joyously twangsome it was the closest this most metropolitan of bands came to country. JA

14.

Rattlesnake Shake

(from Then Play On, 1969)

Beat meat manifesto.

Rattlesnake Shake was the model for a new Mac, a loud, guitar-gnashing declaration that the old blues crusader days were truly over. With Cream and Hendrix’s Experience defunct, Mac muscled in on tougher territory with this thinly disguised ode to masturbation, a thunderous eruption of bendy guitars coiled around a writhing groove while maracas hiss and Green outs drummer Fleetwood as shakerman. Even with mid-song handclaps, it failed to excite the (US) singles chart but the busy instrumental playout illustrates the band’s new thirst for improvisation. MP

13.

You Make Loving Fun

(from Rumours, 1977)

The Mac’s tangled webs/inner circle game.

A thoughtful Christine McVie rocker with an R&B stride and Superstition-like clavinet, You Make Loving Fun belies its consequence-free title. Though written in the flowering of her romance with the Mac’s brown-eyed handsome lighting man Curry Grant – everything was so in-house – her eagerness to reassure her lover suggests foreboding, while sardonic Buckingham guitars and her ex-husband John on bass make this the Mac ménage à cinq plus in troubled miniature. Allegedly, Christine told John it was about her dog. IH

12.

Dragonfly

(Single, 1971)

“In three short minutes he had been and gone.”

The serenity of this ode to an insect – written by Danny Kirwan, based on a poem by W.H. Davies, and released as a single a year after its recording – belied the turbulence in the band: Christine McVie in, Peter Green out and Jeremy Spencer about to follow. As airy and diaphanous as its subject – understated vocals (Kirwan and Spencer) and shimmering guitar (Kirwan) – it’s a very English kind of psych: folky, pastoral, nostalgic, lovely. SS

11.

Need Your Love So Bad

(Single, 1968)

Green sings the blues, heartaches ahead.

Mac’s follow-up single to Black Magic Woman, and a slightly bigger UK hit, Need Your Love… revealed Green as not just a stunning guitarist but a believable blues balladeer. In a compelling interpretation of Little Willie John’s 1955 classic, written by his elder brother Mertis, the original’s piano and sax were replaced by strings as, after a typically reflective guitar opening, Green pleads for love in a firm, beautifully understated vocal. “Need someone’s hand to lead me through the night,” seems highly prescient. GB

10.

Rhiannon

(from Fleetwood Mac, 1975)

As Stevie says, “This song’s about an old Welsh witch.”

When Nicks joined Mac as the free gift that came with Buckingham, it’s likely they had no idea what a force of nature they were getting, or the power of her songs and her appeal to women. Because even with Christine, Mac seemed very much a boys’ band. Rhiannon, one of three Nicks songs on Fleetwood Mac, is mystical, spooky, girlie, addictive, intriguing and anthemic. It established the signature Nicks style that helped make the US Mac a totally different animal. SS

9.

Black Magic Woman

(Single, 1968)

Carlos was here.

Mac’s first Green-penned 45 advertised a fascination with dark forces that seemed deeper than the familiar ‘devil woman’ blues trope. A spectral dual-guitar clang introduces the song while pounding toms and a spooked night vibe transport it far from the band’s beloved Chicago. Green’s ex, Sandra Elsdon, later explained that the meaning lay closer to home – sex, or the lack of it. Carlos Santana, who also knew how to wrench tears from a guitar, would make it a rock standard when he covered it in 1970. MP

8.

The Chain

(from Rumours, 1977)

A Frankenstein’s monster that’s Mac at their bloodiest.

The Chain was a cut-and-shut of stray fragments: some repurposed Nicks lyrics, a chord progression lifted from a Christine-penned outtake, a menacing intro borrowed from Buckingham Nicks’ Lola (My Love), and an electrifying coda jammed by the rhythm section. But its simmering slow-build felt organic, the turn from dustbowl dobro to chugging rock-out – signalled by John McVie’s signature bass line – a triumph, while Buckingham’s needling guitar – minimal and violent, a post-punk precog – whipped the snarled, breathy betrayals into a perfect storm. SC

7.

Oh Well (Part I)

(Single, 1969)

The defiant self-doubter’s blazing self-defence.

Had not the record company overruled Peter Green, Oh Well (Part II) would have been the third melancholy Mac single on the spin. But his doubt-laden flamenco-flavoured instrumental was swapped for its intended B-side, Oh Well (Part I), a driving rock masterpiece of half-jokey existential pessimism of the same title. Recorded within weeks of the Stones’ smash hit Honky Tonk Women, its similarly bathetic cowbell heralds blazing Les Paul and acoustic guitar resolving into the intro of what was now the flip. MS

6.

Albatross

(Single, 1968)

Transcendental levitation.

Peter Green, the man who felt too much. And never more so than on this, the first hit on a spliff made flesh. Fleetwood and McVie’s languorous pedal is masterfully restrained, like two men gently beating gold-dust out of a carpet, but it’s Green and Danny Kirwan’s beatific bends and molten slide motifs that make Albatross the absolute zenith of instrumental bliss, its slow-gliding trajectory seemingly as effortless and far-reaching as that of the wandering seabird it’s named for. JMcN

5.

Don’t Stop

(from Rumours, 1977)

Bill Clinton’s campaign song flips the divorce script.

As bright and urgent as an affirmation stuck to a mirror, Christine McVie’s blast of post-marriage positivity is a masterclass in moving on. The heads-down tack piano roll, wind-in-hair drums and supportive vocal relay between McVie and Lindsey Buckingham make bridge-burning fun, but there remains a sense that not everyone is on board with McVie’s motivational mind-over-matter optimism: “I know you don’t believe that it’s true / I never meant any harm to you,” suggests yesterday hasn’t quite gone, after all. VS

4.

Man Of The World

(Single, 1969)

Peter Green’s exquisite, unheeded cry for help.

Slow and pensive, it rivals Albatross for beauty – but a terrible beauty. Green’s lyrics describe life on the road: girls, money, and the unexpected “How I wish that I had never been born.” This confessional masterpiece, with its evocative guitar solo, stood out in a year when Led Zeppelin released Whole Lotta Love. Mac had been more used to the I-Believe-My-Time-Ain’t-Long macho kind of blues misery; Mick Fleetwood has apologised more than once for failing to heed its message. SS

3.

Go Your Own Way

(from Rumours, 1977)

Buckingham-Nicks: The Reality Show’s Season 1 finale.

A straight-up rocker dragged gloriously off-kilter by cross-rhythms Buckingham dictated to Fleetwood on Kleenex boxes, Go Your Own Way holds simmering, pent-up verses in check until three-part harmonies provide glorious release on each chorus. Nicks wanted to censor Buckingham’s “packing up, shacking up is all you want to do” cheap shot, but it stayed and the song became the Mac’s first US Top 10 hit. Buckingham’s initial inspiration? The Stones’ Street Fighting Man. JMcN

2.

The Green Manalishi (With The Two Prong Crown)

(Reprise single, 1970)

Beware the green-eyed monster...

After Albatross (Number 1 in the UK), Man Of The World and Oh Well (both UK Number 2s), and an excellent album for Reprise, Then Play On (Number 10), Fleetwood Mac were the most fascinating chart band in Britain, each new release keenly anticipated. But The Green Manalishi was not obvious chart fodder. Opening with ominous chugging guitars, and set on a night “so black that the darkness cooks”, it was a minor-key maelstrom of paranoia and dread that you’d have been ill-advised to dance, get high or make out to.

The title creature was “Sneaking around trying to drive me mad / Busting in on my dreams / Making me see things I don’t want to see”. Green composed the music to sound tribal and ancient. It spirals away while he wails like a banshee.

Anyone closely following Green’s trajectory in song might have seen it coming: Man Of The World’s desperation and the sad, spiritual yearning of Closing My Eyes (on Then Play On) were hefty clues he was dealing with demons, but this song, muddy water drawn from a poisoned well, made that explicit.

The Manalishi was green not because it was Green’s personal devil but because it represented money. Further upset by TV images of children starving in Africa, Green attempted to give all his earnings to War On Want and encouraged the rest of the band to join him. Written the day after his dream and recorded at Reprise Studios in Hollywood early in 1970, the band were playing a lengthy live version on their US tour at the time. In the weeks between its recording and release in May 1970, Green had the encounter with LSD, in Germany, that many think broke his mind; though it may simply have expedited something that was coming anyway.

Green, who recalled the German experience fondly, rationalised his subsequent breakdown by blaming this song. “It took me two years to recover from that song. When I listened to it afterwards there was so much power there… it exhausted me.” For Green, it represented some kind of ending, and he left the band. For us, one of the most nerve-tingling 45s ever pressed. JI

1.

Dreams

(Single, 1977)

Here's Stevie with the weather...

Had your ear been to the radio in America in 1977 years ago, you might have guessed that Fleetwood Mac’s new single – destined to be their first US Number 1; regal confirmation of their newfound ascendancy – was an answer song to the same band’s Go Your Own Way, their first US Top 10 hit just a few months before. Though Side 1 of parent album Rumours reverses the order in which you hear the two songs – which might make sense for other reasons – it’s in their sequence as singles, soundtracking the USA during the honeymoon period of Jimmy Carter’s presidency, that they tell a compelling story.

The dong in a ding-dong battle, Dreams is a thing of beauty where the one more loved than loving in an unbalanced relationship responds to her wounded partner’s message of recrimination, self-absolution and go-if-you-must-but-you’ll-miss-me defiance with a matching communiqué. But it’s one whose resigned, wistful tone is its own reproach to her soon-to-be-ex’s emotionalism, as if to say there’s only one adult in the room and it’s not you.

For all the banter about Fleetwood Mac’s public soap opera, the songs, especially on Rumours and especially Go Your Own Way and Dreams, acutely, even painfully, lay out the emotional damage of a love gone sour, but in music close to rapture. Their titanic and lasting popular success testifies not merely to their pop brilliance but to how utterly relatable they are. Who, after all, hasn’t been there?

Lindsey Buckingham and Stevie Nicks’ eight-year-relationship was already foundering when, at the end of 1974, the Californian golden couple were invited to bring fresh songwriting and singing blood to Fleetwood Mac; seizing the chance, they put their personal issues on hold so as not to waste this big break. For everyone the gamble paid off as the resulting self-titled album was a huge hit, creating both commercial and creative momentum which no one wanted to lose. “We were doing something important, we had the tiger by the tail,” Buckingham told me in 1992. “You had to categorise your emotions to make that work.”

Where Buckingham was a methodical musical craftsman who worshipped The Beach Boys' Brian Wilson, Nicks would channel the mood of the moment, sketching songs quickly but seldom seeing them through to the end. Dreams was one such. The band were recording in ocean-side Sausalito just north of San Francisco’s Golden Gate Bridge at the Record Plant, which offered not just state-of-the-art recording technology but a congenial creative environment with “Indian drapes, little hippy girls making hash cookies, and everybody having dinner round a big kitchen table,” Nicks recalled.

At a loose end one evening when not required in Studio A, where the engineers and producers Richard Dashut and Ken Caillat had finally nailed the right kick drum sound, Nicks settled down in the black-and-red decor of Studio B. It housed a central pit – said to have been sunk at the behest of Sly Stone, where folks would retire to chop out a restorative line – and a big black velvet bed with Victorian drapes. It was here that Nicks planted herself cross-legged in front of a Fender Rhodes electric piano, and, unusually for her, programmed a drum beat and “wrote Dreams in about 10 minutes”.

Songbird in flight: Stevie Nicks in the studio (Credit: Costello/Redferns/Getty Images)

The drumbeat is important because, as implied in her demo, a smouldering dance groove lay at the song’s heart from the beginning. On a harmonic bed oscillating back and forth from F to G, the finished article would run on two parallel tracks. Despite a brisk 120bpm in the rhythm section, with John McVie’s pulse-like bass line – virtually confined to F and G – syncing with Mick Fleetwood’s crisp drum pattern and against-the-grain fills, Nicks sings sinuous, wistful melody lines as if from a lovelorn folk ballad.

The combination is both regretfully languid and an irresistible invitation to tap your fingers on the wheel as you cruise down the Pacific Coast Highway. But what Nicks brought to Studio A the day after writing it was a harmonically undernourished song which her fellow songwriter Christine McVie, for one, thought “really boring”. Which is where, in a gesture blending the consummate professional’s commitment to the cause with the emotional self-flagellation of a man assisting at his own whipping, and an implied rebuke to Nicks that she couldn’t even finish her kiss-off song without his help, Buckingham took over.

A band version was recorded in Studio A, but in the end only the lead vocal and drums (an eight-bar phrase looped with its hi-hat phased and mixed high to stress the beat) were retained when they transferred to LA for months of layering. This involved guitars – Buckingham’s dreamily sustained Les Paul licks the most telling colouration – keyboards, conga, vibraphone and doubled three-part harmonies, all shading the song through each of its sections to foster the sense of a changing musical landscape as if seen through a car window. And just for haunting emphasis, the girls alone harmonised on key words interlacing the pre-chorus: “heartbeat”, “stillness” and “lonely”.

Even before the recording was completed, Nicks was in the arms of Don Henley. The golden couple’s relationship was over, but every night they appeared together on-stage, Stevie brought it all back, singing that song. And Lindsey played along. MS

Words: John Aizlewood, Geoff Brown, Stevie Chick, Danny Eccleston, Pat Gilbert, Ian Harrison, Jim Irvin, James McNair, Mark Paytress, Victoria Segal, Sylvie Simmons, Mat Snow.

What? No Silver Springs?!? Get your hands on a copy of MOJO The Collectors' Series: Fleetwood Mac Rumours 1967-2025 to read the full list of Fleetwood Mac's 50 Greatest Songs. Plus, in-depth features and exclusive interviews with Stevie Nicks, Lindsey Buckingham, Mick Fleetwood, John McVie, Christine McVie and Peter Green - ORDER HERE!

Main photo: CBS/Getty