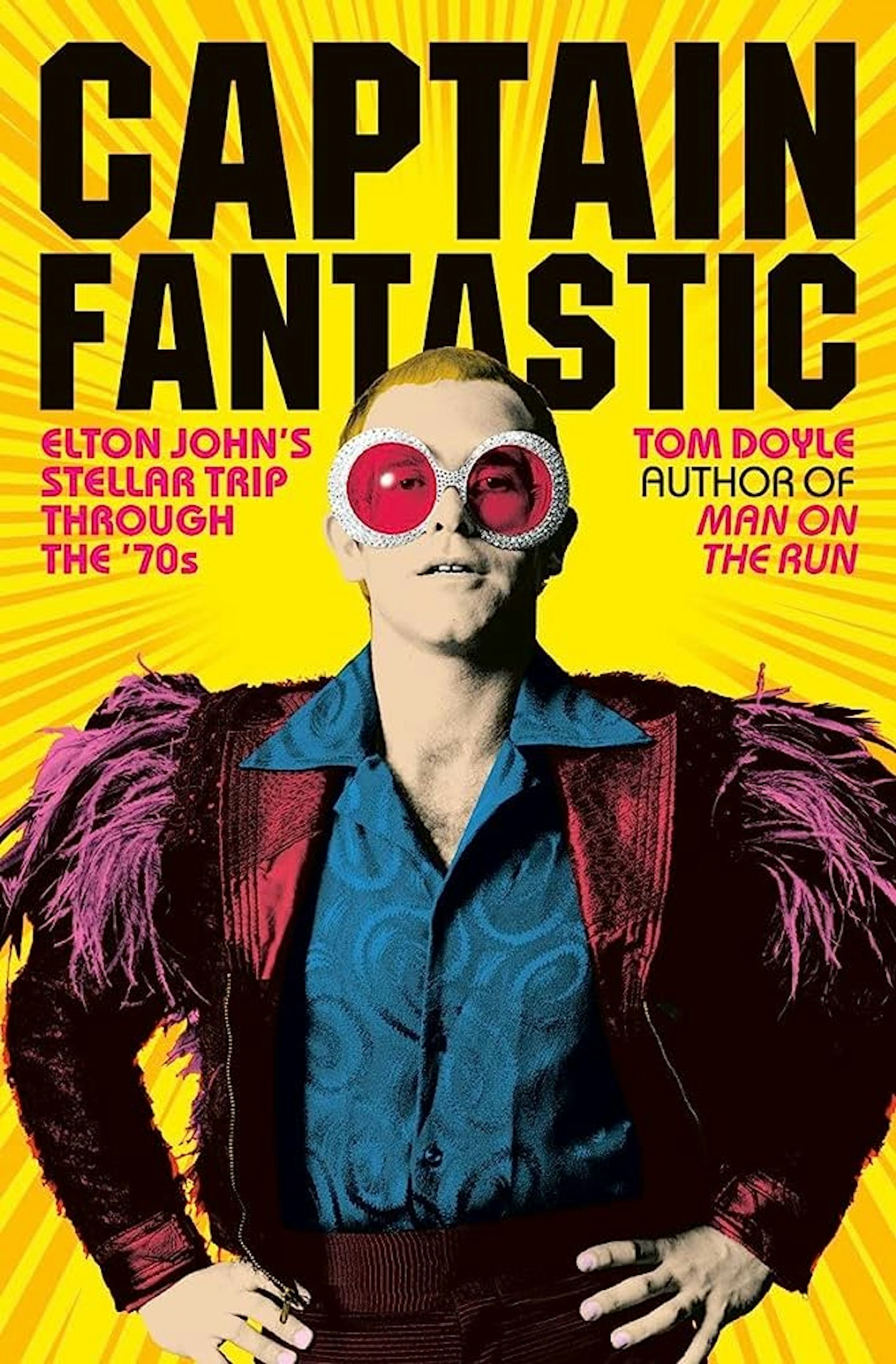

In 1970, after years of jobbing Joanna-bashing and contract songwriting, Elton John was ready for fame. Or was he? In this extract from his book Captain Fantastic: Elton John’s Stella Trip Through The ‘70s, MOJO’s Tom Doyle revisits the US debut performance that turned a chubby troubadour into the future of rock – and now Brian Wilson damn near scared the life out of him.

Captain Fantastic: Elton John’s Stellar Trip Through The ’70s by Tom Doyle is out now on Polygon.

It was the 21st day of the eighth month of the new decade. The second year of Nixon’s doomed presidency and the fourth week at Number 1 for Close To You by The Carpenters. The temperature in Los Angeles was hovering around 75 degrees.

Up and down Sunset Strip, past the Continental Hyatt where Elton John, his band and entourage were checking in, moved the everyday parade of the supercool, the misfits and the bums, while here and there hippies on the sidewalks hawked copies of the Free Press for 25 cents to cruising drivers: “Don’t be a creep, buy a Freep.”

Nine miles southeast of the Hyatt, at the Hall Of Justice, the Manson trial was into its second month. Weirding out those forced to attend it, glazed female members of Manson’s Family hung around outside the building, wearing sheathed hunting knives, Xs burned with a soldering iron onto their foreheads in imitation of the facial carvings of their dark-eyed leader. By night, they slept in bushes or a parked van.

As edgy and dangerous as it was, the atmosphere in LA didn’t affect Elton John in his music-headed bubble, his eyes filled with stars and stripes. Eight of them had flown over from London, lining up in front of a red London bus for a cheesy photo opportunity. Elton stood in the foreground, smiling sheepishly in his beard and dungarees. Down the line ran a procession of faces whose expressions ranged from sunny grins to mild bemusement or insouciance: lyricist Bernie Taupin, bassist Dee Murray, drummer Nigel Olsson, and the London-chic and slightly dandified trio of David Larkham (sleeve designer and photographer at Elton’s UK label, DJM), producer Steve Brown and Elton’s manager Ray Williams, over whose left shoulder road manager Bob Stacey peeked at the camera.

It was four months since Elton’s eponymous second album had emerged to indifference and poor sales in the UK, and for weeks the people at his new US label – unfashionable MCA imprint Uni – had been forcefully pumping up expectation in the city ahead of the artist’s appearance. Publicist Norman Winter had adopted a bold strategy: let’s treat him as if he’s Elvis opening in Vegas rather than an unknown hitting town for the first time. Amazingly, it had worked, and as a result, Elton was all over local radio, with posters in every record store.

That night, Elton went to the Troubadour, the 500-capacity hipster hangout on Santa Monica Boulevard, to check out The Dillards, the Missouri bluegrass group who’d recently gone electric. Forever the fanboy, he was “knocked out” by them, but shocked to learn that his support act at the club the following week was to be David Ackles, the former child actor-turned-purveyor of intense theatrical songs delivered in moody baritone. Elton, a huge admirer, immediately tried to have the bill inverted, to no avail. “We could not believe we were playing over David Ackles,” he told me in 2006. “He was one of our heroes.”

With a few days to kill before the opening Troubadour show on Tuesday, the first of a mind-boggling six-night residency, Elton rented a Mustang convertible to get around. His main priority was to visit record stores and stock up on American discs actually bought in the United States. Meanwhile back at the hotel, more mundane matters prevailed. Nigel Olsson, lacking a hair dryer to blow-dry his long and carefully-tended locks, had Ray Williams call a friend, Joanna Malouf, to ask to borrow one. She wasn’t at home, but her flatmate Janis Feibelman was. Soon after, Janis arrived at the Hyatt with her sister Maxine in tow, who instantly caught Bernie Taupin’s eye.

The next day, everyone, apart from an increasingly nervous Elton, went on a road trip to Palm Springs. Alone and stewing in his hotel room, his anxiety pulling his mood downwards into an almighty huff, he called DJM boss Dick James, and moaned that Ray Williams had abandoned him.

He didn’t have long to fret, however. As a Uni Records artist, Elton now shared the roster with Neil Diamond, and so the company arranged for him to go and visit his new labelmate at his house off Coldwater Canyon for some encouragement before the first Troubadour show. Upon arrival, Elton’s nervousness began to get the better of him and he seemed painfully shy and socially awkward. Diamond thought: This kid is never going to make it.

Day by day, the pressure in Elton’s mind had been building. The night before the show, he suddenly blew, standing up in the middle of a packed restaurant and saying that was it, he was going home. The scale of what he’d let himself in for was throwing his head into turmoil.

Not that he really needed to worry. Soundchecking at the Troubadour the next day, his mood changed. He instantly felt at home. The band was clearly polished and more than ready for the show. “We were like a new engine,” he said. “We’d done our mileage. We were run in.”

Here he was, on-stage at the venue where Lenny Bruce had been arrested for obscenity in ’62, where The Byrds had found one another in ’64, where Joni Mitchelland Neil Young had made their starmaking debuts, and where he was now playing a piano that Laura Nyro had touched only two weeks before.

Everything around him seemed to blur his twin realities as fan and performer and serve to both unnerve and empower him. Reg may have been feeling jumpy and wired about the whole affair, but Elton was now supremely confident.

Walking into the venue mid-afternoon, Uni marketing man Rick Frio was taken aback: “The three guys were on-stage and the first thing I thought was that they were playing the record behind them. There was so much music coming out of those three fellas that it was incredible.” He immediately called Russ Regan back at the office. “I said, We’re home free, it’s gonna work. ’Cos up ’til that point, we were doubtful. I mean, we had never seen them, had never even met them, and all we had was the record. It was gangbusters from then on.”

"Right place, right time. You seize those opportunities."

Elton John

The night of the show, the Troubadour was packed. Uni’s determined push ensured a respectable smattering of celebrities seated around tables in the club, including Quincy Jones, Mike Love of The Beach Boys, Gordon Lightfoot, Danny Hutton of Three Dog Night, and the formidable folk blues singer Odetta, all waiting for the appearance of this 23-year-old nobody, Elton John. “It was very hot and smoky and a great vibe,” he recalled. “I honestly think they weren’t expecting what they were gonna see.”

Come 10 o’clock, Neil Diamond walked out onto the stage to say a few introductory, if oddly noncommittal, words. “Folks,” he began, “I’ve never done this before, so please be kind to me. I’m like the rest of you – I’m here because of having listened to Elton John’s album. So I’m going to take my seat with you now and enjoy the show.”

Then Elton stepped into the light, colourful and alive and a startling contrast to the half-lit and glum-looking individual on the cover of his eponymous LP. He sat down at the piano in an outfit designed by Tommy Roberts of London’s Mr Freedom boutique: yellow bell-bottomed dungarees with a grand piano appliquéd on the back, a long-sleeved black T-shirt bearing white stars, and, to complete this outlandish look, white boots affixed with green bird wings.

At first, the crowd didn’t appear to be particularly impressed, as he launched solo into Your Song before Dee and Nigel slid in to join him on the third verse. But as early as the second number, he began to transform amid a pummelling and gutsy-voiced Bad Side Of The Moon. He was up and away. In his mind, he was competing with The Rolling Stones, not mild-mannered singer-songwriters trapped behind a piano. By song three, Sixty Years On, which dramatically built from delicate piano arpeggios to thunderous instrumental passages, a far cry from their more introspective stylings on vinyl, he knew he had them.

“With a three-piece band,” he pointed out, “there’s no way you can just sit there and interpret those songs à la record, because it was an orchestral album. So we went out and did the songs in a completely different way and extended them and extemporised and just blew everyone away.”

As the show rolled on, he fuelled the intensity, through Border Song, Country Comfort, Take Me To The Pilot, and then, to make the point explicit that inside this apparently meek character beat a rock’n’roll heart, Honky Tonk Women. Firing into the set closer, the as yet-unreleased Burn Down The Mission, he kicked the stool away and lunged into the vamping sections, launching his heels into the air for a series of handstands as he stretched the song over the 10-minute mark with detours into Elvis’s My Baby Left Me and The Beatles’ Get Back. A shocked Neil Diamond was cheering so loudly that he spilled his drink.

“I was leaping on the piano,” remembered Elton, still thrilled by the memory. “People were going, ‘Oh my God.’ Right place, right time, and you seize those opportunities.”

It was the performance that made him. Russ Regan was amazed to discover that within the space of 45 minutes, he’d landed himself a star: “I knew we were going all the way. I just knew it.” The Troubadour’s owner, Doug Weston, was similarly astonished. Having witnessed scores of landmark debut performances at his club, he reckoned “no one had captured the town as completely and thoroughly”.

But still, afterwards in the dressing room, Elton fell to earth and some of Reg’s awkwardness returned. Uni publicist Norman Winter brought Quincy Jones backstage and introduced Elton to him as “a genius”. Elton was horrified. Later he angrily tore a strip off Winter: “Never do that to me again.” People were telling him he was the greatest. But inside, he didn’t feel like the greatest. “I don’t think I ever believed the hype,” he reasoned.

The day after the show, he was interviewed by Rolling Stone magazine for the first time and came across as self-effacing and “oddly subdued… almost fragile” to writer David Felton. “I don’t want the big star bit,” he declared. “I can’t bear that bit. What I want is just to do a few gigs a week and really get away from everything and just write, and have people say, ‘Oh, Elton John? He writes good music.’”

Of course, he protested too much. But the admission revealed the schism that was to widen as his career progressed: the desire for musical credibility versus the bright lure of the showbiz spotlight.

The second night, he looked up from the piano halfway through Burn Down The Mission and there in the second row sat the long-silver-haired figure of Leon Russell, staring back. “I nearly fucking shit myself,” Elton laughed. “Leon was such a striking-looking man and my biggest influence at the time, without question.”

Meeting him in the dressing room after the show, Elton was relieved to discover that instead of being annoyed that he’d cribbed some of his eccentric rock’n’roll piano player act, Russell was friendly and complimentary and even invited Elton to his house the next day. He turned up suffering with a throat that was ragged from two nights of belting it out. Russell gave him a tip: mix one spoonful of honey and one spoonful of cider vinegar with the hottest water you can take, gargle it for a minute, spit it out, then do it again and again. “I’ve done it from that day,” Elton pointed out.

On the morning before the third show, August 27, came the confirmation, on page 22 of the Los Angeles Times, that something vital had happened that first night at the Troubadour. The paper’s highly regarded rock critic, Robert Hilburn, had submitted a review of the show that no one could ignore:

“Rejoice. Rock music, which has been going through a rather uneventful period recently, has a new star. He’s Elton John, a 23-year-old Englishman whose United States debut Tuesday night at the Troubadour was, in almost every way, magnificent.

His music is so staggeringly original that it is obvious he is not merely operating within a given musical field. He has, to be sure, borrowed from country, rock, blues, folk and other influences, but he has mixed them in his own way. The resulting songs are so varied in texture that his work defies classification into any established pattern…

…By the end of the evening there was no question about John’s talent and potential. Tuesday night at the Troubadour was just the beginning. He’s going to be one of rock’s biggest and most important stars.”

Elton was floored. “It was a turbo review,” he enthused. “It spread to New York, Chicago… it really kick-started our career and in a hugely quick way.” Calls started coming in from the promoter Bill Graham, and from the producers at The Ed Sullivan Show.

The review didn’t just cement Elton’s reputation. Its glowing praise bolstered his confidence and reinforced his self-belief. From the third show on, he came further out of his shell, displaying a campiness on-stage that he had previously hidden from view.

That day he’d enjoyed a trip to Disneyland, where Uni had managed to lay on the celebrity treatment for him, ensuring he was whisked to the head of the queue. He left having bought a pair of Mickey Mouse ears. That night at the Troubadour, in combination with a pair of shorts, he wore them to perform Your Song. It was a glimpse of the Elton of the future.

In the days that followed, the Los Angeles music community further embraced Elton and Bernie Taupin. Danny Hutton arranged for them to visit his friend, the drug-damaged Brian Wilson, at the time slowly reconnecting with his music by writing seven of the 12 songs on The Beach Boys’ upcoming LP Sunflower, set to be released on the last day of August. As they

arrived with Hutton and his girlfriend, the actress June Fairchild, at the gated entrance of Wilson’s Bel Air mansion, Elton’s and Bernie’s minds were reeling. Danny pressed the intercom and Brian answered, jokily singing the hook of Your Song maniacally sped up: “I-hope-you-don’t-mind-I-hope-you-don’t-mind-I-hope-you-don’t-mind.”

“He was not well at the time,” says Elton. “His wife, Marilyn, was fabulous: ‘You wanna hamburger, Brian?’ We had dinner and the dining room was filled with sand. He went upstairs to introduce us to the kids, woke them up: ‘This is Elton John, I-hope-you-don’t-mind.’

“Bernie and I were freaking out. I’m from Pinner, he’s from Lincolnshire. We hadn’t taken a drug in our lives.”

After dinner, Brian led them into his home recording studio to play them the master tape of Good Vibrations. Not more than 10 seconds in, he pressed the stop button, confused, saying, “No, that’s not right.” Then he tried to sell Elton his grand piano. At four in the morning, they left, completely disoriented. “I mean, we were absolutely in awe of this man,” Elton marvelled, “but freaking out because we’d never been in such a weird situation.”

Weirdness abounded throughout this eye-opening California trip. Another night, Elton drove in the Mustang up to Hutton’s place high on Lookout Mountain Avenue in Laurel Canyon, the dropout sanctuary of the rock aristocracy. In these jumpy times, though, as the hippies were tipping towards dangerous hedonism, the Canyon had increasingly become a magnet for unsettling freaks and drug-peddling criminals. Worse, the collective drug paranoia of these over-indulging artists had been rendered horrifically real by the brutality of the Manson murders.

Blissfully tuned out from these disturbing frequencies, there at Hutton’s house Elton met Van Dyke Parks, the cerebral, bespectacled lyricist for The Beach Boys’ aborted Smile album. They had dinner and Elton played Hutton’s piano to entertain them. They stayed up all night, and sometime after seven in the morning, he got back in the Mustang.

Driving down the hill on Laurel Canyon Boulevard, heading home to the Hyatt, Elton felt strangely energised. His time spent in Los Angeles had seen him grow up and get wise. He’d met some of his heroes, but he’d also rubbed shoulders with people he considered to be “con men and hipsters”. Elton realised he could see through them. Inside, he pledged never to end up like these sad music-biz hustlers.

He thought to himself: “God, I was so naive a week ago. And you know what? It’s really weird. I’ve never stayed up ’til seven in the morning in my life. I really feel good. I must be excited.”

“Years later,” Elton grinned, “Danny told me that they’d put cocaine in my food. I’d no idea the first time I did cocaine.”

In the space of four months, Elton John went from being a nobody to a star in America, attracting famous fans in Bob Dylan and The Band with the October ’70 release of Tumbleweed Connection. Over the next few years, he would become the biggest rock phenomenon in the US since The Beatles, outselling The Rolling Stones and Led Zeppelin. But as he came to terms with his success and sexuality, the Elton mask sometimes threatened to eat into the face of Reg Dwight, in a decade characterised by skyscraping highs and plummeting lows.

Captain Fantastic: Elton John’s Stellar Trip Through The ’70s by Tom Doyle is out now on Polygon.