Smokey Robinson’s exquisitely crafted songs and singing of infinite style helped create Motown. Then death and divorce pushed him to the edge, but music pulled him back. In 2014 MOJO's Geoff Brown sat down to hear his story...

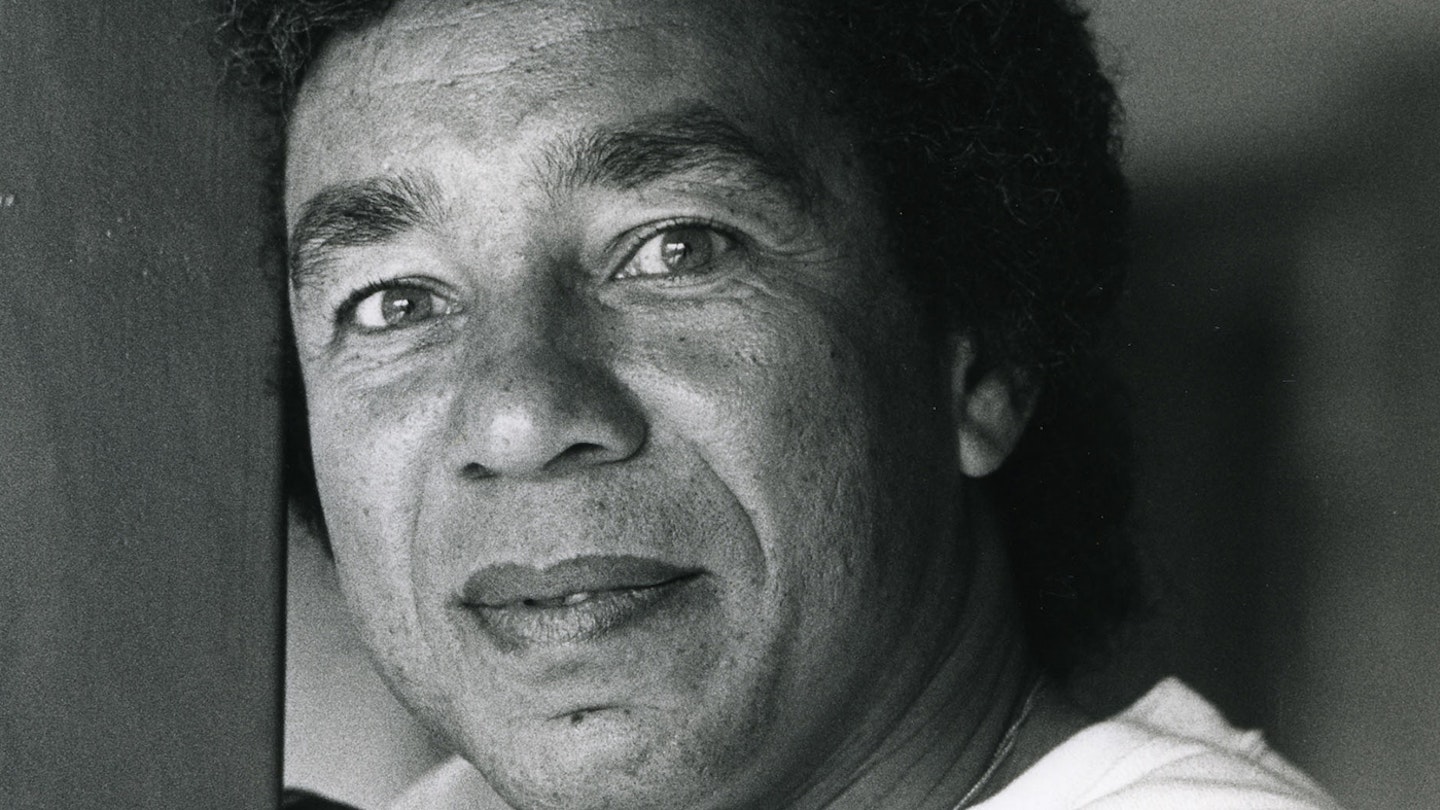

DURING A BRIEF LONDON STOP-OVER, en route to perform at Edinburgh Castle in celebration of the start of the Commonwealth Games, Smokey Robinson is taking time out to promote his new album of duets. He’s looking fit, dressed in black sweater, black slacks, black slip-on shoes. The head of tight black curls remains, a gold chain hangs around his neck, but most striking are the eyes – large, opaque, pale green irises that seem to both look inside you and disguise what he might be thinking.

Down the decades this writer has interviewed Robinson four or five times from the mid ’70s to late last year for the MOJO 20th anniversary. He’s always been a friendly and open talker, despite some facts seeming to change over the years for reasons, one surmises, of natural diplomacy.

Born in 1940 into a preposterously febrile hotbed of Detroit musical talent, William Robinson exemplified the artistic excellence of Motown, the most totemic black-owned company of the 20th century. Joining founder Berry Gordy virtually from the start, Robinson was a hit songwriter, producer and artist whose ear for a phrase enabled him to spin lyrics of gold, and with his beautifully delicate high tenor gave the melodies wings, be it investing conversational turns of phrase like, “I’m just about, at the end of my rope,” with a real emotional ache in Ooo Baby, Baby, this writer’s favourite Smokey confection – well, today, anyway – or writing any number of perfect songs for The Temptations, Marvin Gaye, Mary Wells, The Marvelettes, pretty much the entire Motown roster. Many of those classics have been covered by white pop and rock acts from You’ve Really Got A Hold On Me on 1963’s With The Beatles onwards

Given such a starry history, a brief straw poll in the MOJO office ascertained that, the writer aside, no one knew how William Robinson came by his nickname – that warm, floaty voice perhaps?

How did you become Smokey?

My uncle Claude, he gave it to me. He was also my godfather. He started taking me from when I was two or three years old to see cowboy movies. I loved cowboys, especially the ones who sang. And he had a cowboy name for me, Smokey Joe. Whenever anybody else asked me what my name was I used to tell them it was Smokey Joe (laughs). It was better than William. And when I got to the age of about 12 they just dropped the Joe off and I’ve been Smokey ever since.

Singing cowboys aside, who were the first singers you listened to?

Oh gosh, I’ve loved singers all my life. The first voice I ever really remember hearing was Sarah Vaughan’s, and I heard people like Billy Eckstine, Frank Sinatra, Patti Page, Sammy Davis and people like that. There was singing in my house at all times. When I got to be older my number one singing idol was Jackie Wilson. And then there was Sam Cooke and Clyde McPhatter, Frankie Lymon and Nolan Strong. I don’t know who influenced me the most. But I know probably somebody did (laughs).

Your parents separated when you were just three. Seven years later your mother, Flossie, died. That’s a lot of pain and heartache for a child to handle.

I was 10 years old and the world stopped. I felt absolutely frightened, alone really. Even though I had a lot of people around me. My mother was what I call a profound speaker. She always spoke to me in proverbs and things like that, and tried to give me wisdom through conversational nuggets.

Your father was less profound?

He was a different character. My father was a really good man. He was not, uh (long pause), he was not a boisterous kind of person unless he’d had a drink. But other than that he was pretty mild-mannered, and he was a good man. He lived to 89.

You started writing poetry and lyrics at a precociously young age. In your room?

No, no, no, no, no. Wherever it hit me that’s where I wrote. I always loved words. I’ve never been that kind of writer that has to go away in a room somewhere, I don’t have to isolate myself from the world and go somewhere private. You could say something during this interview and I’ll say, Oh! That’s a great idea. I might give you credit (laughs).

In Detroit, you meet Miracles Ronnie White at 10, Pete Moore at 13, Bobby and Claudette Rogers at 14 and you’re friends with Aretha Franklin and Diana Ross, all from a relatively small neighbourhood.

I grew up with Aretha and Diane. Diane lived four doors down the street and Aretha lived right around the corner. I’ve known Diane since she was probably eight years old and Aretha since she was probably five.

Did you sing in church with them?

No, no. Aretha’s father [C.L. Franklin] was one of the biggest preachers in the country and occasionally I would go to church there because her brother [Vaughn] was one of my best friends. So occasionally I’d go there, but very seldom.

A little later you met the most significant local in your career, Berry Gordy. We explored that first meeting in MOJO 242. You started as a writer mentored by Gordy, and became a man whose work was vital to Motown’s early growth. Did the relationship between you change?

I don’t know (long pause). Our relationship changed before he even started Motown. When I met him he was a young songwriter in Detroit writing all the hit records, basically, for Jackie Wilson, who like I said was my number one singing idol and I always, even now, when I buy records I want to know who wrote that music. So I knew his name from Jackie Wilson’s records ’cos I had all of them. And when I met him at the audition with Jackie Wilson’s managers we sang songs that I had written rather than currently popular stuff. Shortly after that we just struck up a great relationship and we’ve been best friends forever, before he even started Motown.

As a fellow writer and producer were you competitive with Gordy?

Absolutely. We’re still competitive. We compete against each other for everything now! (Laughs) That was his idea for everything at Motown. He had a saying, “Competition breeds success.” So he wanted us all to compete against each other, which we did. But we were always there for each other, we always helped each other even though we were competing, because everybody wanted the best for everybody else. So if you could do something that would enhance what this person was doing you would do it because we were all brothers and sisters, we were a family growing up there at Motown.

A small cheque made you urge Berry to start distributing Motown nationally.

For [1959’s] Got A Job. I suggested after we’d had a few records that we go national. Because before to get national distribution he would put the release out with other record companies. And so after getting so little back [the cheque for Got A Job was $3.19] I just suggested that we go national. Why not? Nobody was paying anyway, so if we lose money we’re still in the same boat.

Gordy had previously run his construction, decorating and painting business. Did that help in the physical building of the Hitsville studio at 2648 West Grand Boulevard?

Well, Berry bought the house that had a garage attached to it. You could go out of the kitchen through a door and into the garage. So he tore the wall out of the kitchen that was adjacent to the garage and made a control room in there and made a window so you could see down into the garage which became the studio. So Hitsville was a house with a garage attached to it.

“Berry used to have a saying, ‘If we don’t get a hit on them it’s not their fault, it’s our fault.’ Because we wouldn’t have signed them if they weren’t talented.”

There were a lot of meetings, Monday morning production meetings, Friday quality control meetings, song contests.

It built a flow to the work… if you wanted to get a record out you better be on it because there was so much competition and so many wonderful writers and producers.

Did writing to assignment – a Mary Wells record, or a Temptations record or a Miracles record – come easily to you?

We grew up together, so I knew everybody intimately, we didn’t just have a musical relationship, we went to each others’ homes, we went on picnics together, we had parties, every year we had a Motown Christmas party, so we all knew each other socially and intimately rather than just as musical cohorts.

As well as writing and recording you were touring. Did you enjoy that aspect?

I still do, that’s why I still do it. Out of all my work, that’s my favourite thing. You don’t get that anywhere else, you don’t get the chance to have a one-on-one with the fans like that.

Playing live, your first experience at the Apollo in Harlem in 1958 was a tough baptism, wasn’t it?

Oh absolutely! (Laughs) ’Cos the Apollo was the landmark place. It still is. I always hope that if they tear everything down on 125th Street in New York that they leave the Apollo standing because it is the training ground and proving ground for so many wonderful black artists who came before – Ella Fitzgerald, Count Basie, Duke Ellington, Sarah Vaughan, those people got their breaks there and you better be on it when you come there because the audience is used to the best. The first time was horrible for us, they didn’t boo us but we were terrible. We were the first act on. It was our first real professional performance and we hadn’t seen people working like that, so it was definitely a lesson. Ray Charles, he was The Man in my life, he was incredible, because the first day we went there, his orchestra was playing for the entire show. The rehearsals happened at 7 o’clock on a Wednesday morning ’cos the show opened on Wednesday afternoon and ran until [the next] Tuesday. So everybody went to the basement of the Apollo and rehearsed but we didn’t have any arrangements [written out]. The guy who was running the Apollo at the time was bitchin’ about it and Ray came in. He didn’t have to be there, 7 o’clock in the morning, it was his band’s place, but he happened to be there. It was a godsend. He came in, sat down and [wrote] them for us, right then and there off the top of his head. Incredible.

Several of your most special songs, like Tracks Of My Tears, have started with a Marv Tarplin guitar lick or passage.

Well, Marv, he was my most fantastic writing partner ever. He passed on a couple of years ago, of course. But he was very great for me, his music inspired me tremendously and I could always write well to him.

Were the other great musicians you worked with at Motown, like bassist James Jamerson and drummer Benny Benjamin, as easy?

You don’t really realise how awesome it was until it’s over, until you look back, ’cos while it’s happening it’s just happening and it’s every day, it’s just there, it’s what’s going on. You’re working with these guys and they’re playing and you’re having a great time and you’re not really realising the impact of it. If I had known what it was gonna be I’d have saved every scrap of tape and every little piece of paper, every thing, because we didn’t realise we weren’t just making music, we were making history.

What about specific songs – the early Mary Wells hit Two Lovers, for instance, what inspired that?

I was watching an old movie on TV one night, and this woman had these two men that she loved. And see, people think that love is exclusive, “How can you love somebody else if you love this person?” That’s just the way love is. Love doesn’t have no boundaries, no formulas, and no rules, love doesn’t know that. So I thought, OK she’s got these two lovers, she loved them both, and in the movie I think one guy died or something, but I thought about it, What if she has two lovers but they’re the same person? So I wrote that song.

You’ve mentioned that you can write anywhere. You came up with Ain’t That Peculiar in London.

That was Marv Tarplin. We were on tour and he came to me because he had that guitar riff which I thought was awesome. And we wrote the song right here. It was specifically for him. We wanted to get something to follow up I’ll Be Doggone.

You were expert at finding something new in The Temptations’ sound. Your song My Girl switched the Temps’ lead vocal focus from Eddie Kendricks to David Ruffin’s tougher tenor. You’d already moved that focus from Paul Williams to Kendricks.

Yeah. The first record I ever recorded on them, in fact, was a song called I Want A Love I Can See and I used Paul as lead singer ’cos when they first came over Paul was actually like the basic lead singer. This was before David Ruffin got with them. But Eddie Kendricks could sing lead, so we did The Way You Do The Things You Do. The inspiration for me for The Way You Do The Things You Do was Curtis Mayfield. He had a song out with The Impressions called It’s Alright and they sang with this great harmony and I knew The Temptations could sing like that because they had a great harmony sound, and Curtis had this high voice like Eddie Kendricks and I wanted to simulate that if possible.

As a writer and producer you also had a strong affinity with women artists – Mary Wells and The Marvelettes, The Supremes early single Breathtaking Guy – what did you like about women singers?

They were women! (Laughs at stupid question) No, they were my sisters and they were there and if I could get a hit on them I wanted to if at all possible. That was the goal of all the writers.

Were you angry when Mary Wells, who you’d nurtured from 1962’s The One Who Really Loves You and beyond her ’64 Number 1 My Guy, upped and left?

I was disappointed, I wasn’t annoyed. You’ve got to live your life. I tried to talk her out of it because she was making a mistake, as far as I was concerned, but all the vipers are coming after the artists, whispering these sweet nothings in their ears and how much money they can make and how much they’re gonna pay them, so she went for that and that was a mistake. She left, never had another hit.

As an A&R man and producer at Motown was there anyone who never fulfilled their potential to your mind?

Well, yeah, there was a lot of people ’cos when we signed somebody there we thought they were gonna be big! And so a lot of them never were. Berry used to have a saying, “If we don’t get a hit on them it’s not their fault, it’s our fault.” Because these people were talented, we wouldn’t have signed them if they weren’t.

Towards the end of the ’60s you had your first two children, Berry (1968) and Tamla (1970), with your first wife Claudette. How did that affect you?

Oh it was tremendous (smiles). Joy! An incredible feeling. In fact it was one of the main things that inspired me to retire from The Miracles. Because I had been on the road since I was about 16 with them. Claudette, my then-wife, and I had had seven miscarriages, ’cos she was in the group, she was on the road travelling and it was hard. So we wanted children and when they were born it was a whole other feeling, and it was the inspiration for me to say, OK, I want to be home.

And the farewell tour went on for ever.

Well, yeah, (laughs) it went on for about a year. Tears Of A Clown was the reason the tour took place in the first place. I had said I was gonna retire before then and Tears Of A Clown came out [the unregarded track on 1967’s Make It Happen was released in the UK as a single in 1970; became a US Number 1 hit too] and it was the biggest record we ever had. So a lot of wonderful things started to happen for the group and I was told I could not retire from the group at that point. So I went on for another year. They started to audition [for a replacement] and came up with this guy, Bill Griffin, from Baltimore, Maryland, and he went with us on the tour. Every night he was there, watching the show, so when I stepped down he’d be ready.

Did you help with the choice?

Not at all. I knew I wasn’t gonna have to deal with whoever they picked, I wasn’t gonna be around, it was their choice, I had nothing to do with it.

For one of the last Smokey Robinson And The Miracles albums, 1968’s Special Occasion, you recorded the first version of Norman Whitfield’s I Heard It Through The Grapevine, later a hit for Marvin Gaye and Gladys Knight & The Pips. Whitfield had a reputation as a dictatorial producer: ‘Sing it this way.’ Was he like that with you?

No, not with me, he wasn’t quite, but he was definitely that way (laughs). But, yeah, The Miracles and I were the first ones to ever record that but the company thought it was too bluesy for us, which was a drag because apparently it’s just a hit song. Anybody that ever had it out, it was a hit!

Are you as certain, as dogmatic, about how you want your songs sung?

No, because me being a singer I knew that everybody has their own interpretation of a song and once I teach it to you, hey, I want you to be you. I want you to act yourself to it. I want you to feel it, I don’t want you to feel me. So no, I wasn’t like that.

In your different ways, you both got very fine performances out of Marvin Gaye.

Marvin was one of my favourite people ever to work with. When I was producing him we’d be together all day, every day. He’d always be late, but he’d come in and I’d show him a song and he would ‘Marvinise’ it. I couldn’t ask for more than that.

You called him ‘Dad’. Why?

It was because he had bad feet, and he used to walk like an old man, and so all the guys, we called him ‘Dad’. Then he decided he wanted to play American football. He was gonna go out for the Detroit Lions and so he went and had foot surgery to get rid of all the bunions and stuff so he could walk and run properly.

Holland-Dozier-Holland were more big songwriter/producer competition for you.

Oh yeah, they were the guys, they probably had more hits than anybody at Motown. They get a star on Hollywood Boulevard in February, but I’m out of town at that time, I’d love to be there.

When did you get yours?

Oh gosh, I don’t remember. I have two. I have one with the songwriters and one with The Miracles also.

The Farewell tour ended in June ’72 and by August Motown had moved you from Detroit to their new offices in Los Angeles. Without your family.

[It was] traumatic because I really didn’t want to move to Los Angeles but Berry insisted because he was moving everything there. So me being an officer of the company I had to move. I’m very happy that he made [the decision] because LA’s a great place, I’m very happy living there.

But Detroit suffered.

Because of that and the auto industry moving out. It‘s kinda like in a devastated state

right now. I hope something happens to turn it around.

There seems to be some inward investment, Chinese and South Americans buying large plots for redevelopment.

Well, so what? Buy up all they want to buy up, but if they don’t create jobs it’s not gonna mean anything.

In those first months in Los Angeles, did the solitude help you write?

At first I was just concerned with my vice-presidential duties. In Detroit my office was designed to bring in and sign new talent. When we went to Los Angeles [Berry] said, “Well I really trust you more than anyone so I want you to do the financial, you’re going to sign all the payroll cheques.” So at first I’m saying, “Oh, this is great. I can do this,” (mimes signing cheque with a flourish). After you’d signed about a thousand cheques you’re gonna find

a shortcut. My signature now is a scribble – I used to write my name out in long-hand. I enjoyed it very much at first, but after a while you discover it’s not really you. It became misery for me, not doing showbusiness. So I was totally deskbound. I was composing some songs, thinking about writing some stuff for some other people but nothing really seriously. But after about three years Berry came to me and said, “You’re miserable, I want you to get out of here.” So I did and I wrote a song called A Quiet Storm [1975].

Even before that, on your 1973 debut solo album Smokey with songs like Sweet Harmony, Baby Come Close and Just My Soul Responding, you seemed to be developing a new style for male singing, songwriting and production counter to the prevailing winds of disco and funk.

Yeah, Quiet Storm is now a radio format in the United States. I was surprised totally, never expected that. I wasn’t thinking about disco, wasn’t thinking about any of that, I was just thinking about trying to get me some hits and come back into showbusiness.

You weren’t tempted to write something like a Mickey’s Monkey or a Going To A Go-Go for the disco age?

No, no. I wasn’t a disco singer so why should I try to be somebody I’m not?

After massive success in the ’60s as a group singer and songwriter/producer and similar ’70s success as a solo artist, you hit a brick wall in the ’80s when your father died, your marriage to Claudette ended in a messy divorce and drugs got a hold on you. You’d never seemed a candidate to go that route.

Yes. Horrible. Horrible. It goes to show you about when you start to dibble and dabble into heavy drugs, they don’t care what you do, they don’t care who you are, what you’ve accomplished, what position in life you are in, whether you’re rich or poor, black or white. Drugs just overtake you. I wrote a book [Inside My Life, 1989] as a result of that. People had been trying to get me to write a book for a long time but as a result of that, as a result of my healing from that, I wrote a book to explain that to people, in the hope that I could help some people to know that once you let them in, they’re in until you kick them out. And so that was a rough time.

You didn’t go down any accepted route to kick drugs out either.

No, no, no, no no. Personally I’m very blessed and I realise that. I am not a religious man, but I have a wonderful relationship with God. I talk to God every day of my life. And so God stepped in and brought me back from the edge of the cliff, and here I am.

Then in the 21st century you’ve done varied, interesting, mature albums. Like Timeless Love, an album of standards, which took you back to the start, really.

Absolutely, the music I grew up with. I love those songs – that was back in the days when song was king. It turned around, somehow, in the late ’60s and the ’70s and the song was no longer king, the artist was the focal point. But when the Gershwins wrote something like Our Love Is Here To Stay, all the artists recorded it. Everybody. Song was king.

Time Flies When You’re Having Fun celebrated your 50th anniversary in the business…

Yeah, that’s how I feel about life. Because I look back on my life and gosh, you know, 1958, that’s a long time ago but it seems like (snaps fingers) that. (Laughs) My kids are growing and I got grandbabies! I have three of my own and then my wife, Frances, she has five so we have eight altogether. So we been married going on 13 years.

On your latest record, Smokey & Friends, you duet with singers from Elton Johnand Steven Tyler to John Legend and Mary J Blige.

Randy Jackson [The Jacksons, American Idol] is the producer and he contacted the people and asked them what their favourite Smokey Robinson song was and that’s the song I recorded with that artist. And we basically let them put their own flavour into it – we talked before about an artist putting their own touch on a song. So that’s how the album was made and I’m very excited. I’m happy and joyful they picked a song at all (MOJO laughs). I really mean that ’cos as a songwriter that’s my dream come true. I want people to want to sing my songs, from now on, for ever. And when I know these people listen to my music, most of them are songwriters themselves. That’s a really flattering and wonderful thing.

This article originally appeared in MOJO 251.