Radiohead have just announced their first shows in seven years. Taking place in Spain, Italy, the UK, Denmark and Germany, the concerts mark a regrouping of the band after a prolonged hiatus during which time many fans had feared Thom Yorke and Jonny Greenwood were now content to focus instead on The Smile, their group with drummer Tom Skinner. It's been almost ten years since Radiohead's last album, 2016's A Moon Shaped Pool. Whether these shows will be a bellwether for a tenth Radiohead album remains to be seen (you can catch up with their work to date with our complete rundown of every Radiohead album HERE). For now, though, enjoy this classic Radiohead interview from the MOJO vaults.

In May 1997, MOJO's Jim Irvin travelled to Barcelona for the European unveiling of Radiohead’s third album, the eagerly anticipated OK Computer. After a long day of promotional engagements, frontman Thom Yorke finally settled on the roof garden of the group’s hotel to discuss the fascinating creative processes and strange internal band equilibrium that marked the making of perhaps their finest record. “It’s basically chaos a lot of the time,” the singer revealed...

It’s Thursday May 22, 1997, a searing summer’s day in the Catalonian capital. Three things are creating a buzz in Barcelona this morning: the pavements are sprouting strange kiosks for some Spanish business festival, students are marching in protest down Las Ramblas, and a top pop group are in town for the launch of their third album. Radiohead have been here since Monday, following warm-up shows in Lisbon, Portugal. They spent yesterday talking to the press and TV swarming here from all over the globe and tonight, at the modest Zeleste Club, they’ll perform for the official European unveiling of the masterful OK Computer.

Thom Yorke is in the foyer of the Hotel Condes des Barcelona. He’s dressed as an affluent tourist from Ursa Major: shiny slate-coloured zip-up top, rucksack, baggy trouserings in some unnameable man-made fabric and huge hi-tech trainers that look as if he’s stepped into a couple of hovercrafts. He’s with his close friend Dan Rickwood, aka Stanley Donwood, the man responsible for all Radiohead’s artwork, and is due any minute at an internet press conference linking Australasia, South America and Dubai.

In the meantime, MOJO asks a stupid question: Why Barcelona? A single Yorke eyebrow is raised above his yellow shades, “Why do you fucking think?” it says, though its owner remains silent.

The virtual chinwag is a wash-out. The system crashes within minutes. All the band except Thom are ushered on to an MTV interview. The Radiohead juggernaut is going gently into overdrive and the world’s media are queuing up to throw themselves in its path.

Recorded over a year, OK Computer was, like The Bends, another extended struggle to perfect the group’s working methods. They liked the simple way they’d recorded Black Star (on The Bends) and Lucky (for the Bosnian charity record The Help Album) with engineer Nigel Godrich, and asked him to build and man a mobile studio for them. Work began at The Fruit Farm, a converted apple store near Oxford the band used as rehearsal space, then moved on to Jane Seymour’s Elizabethan mansion outside Bath (features include terraced gardens, full-sized ballroom and framed photos of Jane in her undies in the bathrooms).

With just the band, Godrich and a cook present in the rambling property, they found it intimidating to begin with. “But,” says Godrich. “we made it our own and developed this real sense of freedom. We could play croquet in the middle of the night if we wanted!”

Having learnt from the The Bends, they decided to break the songs in live before completing the record. “Radiohead have displayed a dogged determination to come and tour America and tour America and tour America,” says Pablo Honey co-producer Paul Q. Kolderie. “And not only that, but do all the stuff you have to do, go to those retail dinners and so on. Thom would sometimes make a bit of a scene, and he wouldn’t always be there, but they’ve really made the effort to make friends in the industry. And that reflects a conscious strategy on the part of Chris Hufford and Bryce Edge.”

Between the release of The Bends in March 1995 and the completion of OK Computer earlier this year, Radiohead toured America no less than five times. Hufford and Edge followed the approach of Miles Copeland with The Police and Paul McGuiness with U2: keep coming back, slogging your way through the boondocks and college towns, and America will be yours. Says Ed O’Brien: “Because they became so huge in Britain very quickly, bands like Happy Mondays and Stone Roses came to America with completely the wrong attitude. You have to keep touring.”

Jonny Greenwood agrees: “There are lots of double standards with British bands when they talk about America. They like to talk badly about it, yet they want to conquer it. We’re in awe of America.”

Radiohead’s new material was premiered on a 13-date American tour supporting Alanis Morrissette. Capitol was delighted with what they were hearing. In those surroundings, new songs like Electioneering sounded like anthemic US radio hits. They began to pump up the idea of Radiohead as saviours of stadium rock. “[Capitol] thought, This album is going to be chock-a-block with radio-tastic singles and we’ll just have it away majorly,” laughs manager Chris Hufford. “But when the record was finished, Electioneering ended up being this very abrasive, garagey thing and the other songs [the label] had liked didn’t even make it to the album.

“There was lots of ‘Ooh dear, this isn’t quite what we thought the record was going to be, I have to say we’re a bit disappointed.’ But by that time the UK had grabbed it and said, ‘This is fucking awesome!’ So we steamed in and said to America, Get your industry heads off, forget the bloody singles, just listen to it like a punter for a few weeks and you’ll realise what an amazing piece of work it is. Thankfully, that’s what happened. They started saying, ‘You’re right, this is amazing, but now what the fuck do we do with it?!’”

Friday May 23, 1997, Barcelona. Another day of promotion. The band assemble in a large suite at the Meridian Hotel to face today’s five-page itinerary of tasks. At 11am Thom is talking to French magazine Rock & Folk while Jonny meets Christian Fuchs from Austrian radio, Phil’s doing a Belgian newspaper, Ed and Colin are being interviewed by Austrian magazines. After lunch, while the others record a bunch of TV slots, Ed will be chatting to someone from the German station amusingly known as Radio Fritz.

In the afternoon, a cluster of German journalists arrive to find that celebrations for Phil Selway’s 30th birthday are taking place. The EMI posse have purchased a cake and Phil personally hands a slice to each of the patiently queuing media-folk. A TV crew is filming another TV crew filming a press interview. A photographer is taking pictures of all the photographers taking pictures.

By the time MOJO’s turn comes (we’re booked in at 18.45) everyone’s looking a bit frazzled. In the suite that acts as the Radiohead HQ, Chris Hufford is rolling a restorative spliff and fielding calls on his mobile, making plans with partner Bryce Edge – in another part of town – to dine with some very senior EMI mandarins the following week. As soon as the call is over, Hufford’s mobile goes again.

Carol Baxter, from EMI’s international office, nursing a large gin and tonic, tells me about the Japanese “Phil Is Great” fan club, a curious clique of female EMI Japan employees entirely devoted to being nice to Radiohead’s drummer. At their meetings they serve Phil his favourite foods, then play bingo. Worried about offending the rest of the band, the club has elected to close itself.

The schedule is running almost an hour late. Thom’s still in with a Swede. Chris is concerned that his charge may be fried. “What time are you leaving tomorrow?” he asks MOJO ominously. Yorke emerges just before 8pm with a thousand-yard stare. Chris gets him into a huddle to discuss what he’d like to do about the MOJO interview. There’s an intriguing frisson to their conflab, the coming together of mentor and meal-ticket. Yorke’s shattered, he’d like to talk to MOJO but would also like to go off-duty some time before midnight. He needs to freshen up, he says. I suggest a quick turn on the bidet. Yorke has a short, explosive laugh. His manager decides to finish their discussions out of earshot. We’ll repair to the band’s hotel while Chris and Thom confer in a separate cab.

The Claris is the Starship Enterprise with ensuite bathrooms. Its plush, space-age ambience seems entirely apt for Radiohead. As we climb the walls in an external elevator pod, Thom points out the absurd phallic symbols languishing in a modernistic pond below. In the rooms, he says, are crazy Bang & Olufsen TVs that come out of the wall and look at you when you turn them on. We gate-crash some sort of reception in the roof-garden and Thom settles himself on a pine lounger by the tiny pool.

Considering the kind of day he’s had at the rock face he’s in good spirits. He laughs easily and his voice shows little sign of fatigue.

**So, Thom, were you happy with last night’s show?

**Yeah! Fuck.

You said on-stage that you were really nervous.

All the way through, yeah, every note. It’s been a long time and all the stuff going on around us is really, really frightening and just trying to keep your head… I’m glad we did. All I know is the feeling afterwards of calm for the first time in months… Which of course has been completely fucked over today.” He rolls his eyes and laughs.

We talk at length about the making of OK Computer and its themes.

Have you worked out how to make this promotional stuff bearable? “Could be much worse because last time we were flying to different countries every day, going in and out of X-ray machines, getting on and off planes, there’s nothing going to fuck you up quicker than that. So this time we’ve used our position.

**How long do you think the campaign for this record is going to go on?

**Campaign… pfff (laughs).

It’s best not to know, I suppose.

Yeah, fucking right. I’m just thinking about tomorrow Because I get really hysterical otherwise.

Ever castigate yourself “This is what you get for writing some songs, you bastard. This is the price…”

Yeah. It’s nothing… I’m not really here and this is not really happening, so that’s fine.

Do you have a Thom Yorke promo persona, here we go, promo head on?

(Long pause) Yeah. (Laughs) Er yep. Yeah.

How does it manifest.

Er, the ability not to give a toss.

What’s the silliest question you’ve fielded today?

I had one French guy who I spent three-quarters of an hour with, who just went on about Creep, and I couldn’t bother to argue with him I was so fucked and he was saying, “So how was your childhood?” I sort of answered it but I’ve no idea what I said, I was just going, “La la la la.”

Pablo Honey – you were searching for a voice. Every song’s different. Did you work on that on The Bends?

No, it was just a confidence thing. The thing about Pablo Honey is that it was done like a demo. OK, let’s do it in three weeks, don’t worry about it, no one will hear it anyway, it’s our first album, whatever… and then so many people bought it. Ed always goes on about not judging bands on their first album, we were still forming and didn’t have any idea what we were doing.

Can you remember a moment when you thought, “This is my voice, I’ve got something here that I like”?

Fake Plastic Trees. I spent a lot of time and effort on this album getting to the point where I was not doing voices like mine at all. Obviously using the computer and the voice on Karma Police and the voice on Paranoid Android and the voice on Climbing Up The Walls – they are all different personas. It was a really liberating thing. The one reservation I had at the end of The Bends was that it didn’t matter what I was singing, I could be singing “fish and chips” and it still sounded melancholic and it was getting very frustrating because I didn’t feel I could write things because they didn’t fit with this voice – the one that I’d ended up with.

So a lot of time and effort for me was spent trying to change that. Though it’s not blatantly obvious. But it was something I was acutely aware of. The thing about OK Computer, it wasn’t this need to exorcise things within myself, it wasn’t digging deep inside, it was very much a journey outside and assuming the characters and personalities of the voices of other people. Obviously, I’m restricted, but like Lucky, the lyric and the way it’s sung I think is really positive, really exciting. No Surprises is someone who’s really trying to keep it together, but can’t. Electioneering is a preacher ranting in front of a bank of microphones. It’s like taking Polaroids of things that are happening at high speed in front of you…

What was the chief imperative when you want in to make this album?

The chief imperative was to have complete and utter freedom. And that included producing it with Nigel Godrich, who we’d done Talk Show Host and Lucky with, and he was sort of our age and the same headset… I mean mindset. And we spent a ridiculous amount of money buying gear [Parlophone reportedly gave the group £100,00 to spend on equipment] because we wanted to set up our own studio and take it wherever we wanted. It was all about freedom. We spent months and months getting to the point where all this other stuff around us was irrelevant. We had this sort of nostalgia for the time when me and Jonny used to do four-track stuff. We’d just do it when we felt like it, go round his house, write a song, tape it, fuck off home and that’s what we were trying to do, sort of make it our own, learn how to use all the gear, take it on good and bad. It was a way of trying to maintain freedom and a way of dealing with the fact that everyone was interested.

The Bends was like a huge confidence thing for a me, a great eye and ear opening: “Great, I’m not going to write about myself because there all these amazing things all around me and I want to write about those. And we’re just going to do what we want and make mistakes and just put that energy into it.” Great. Liberating. But also terrifying, because you’re taking on the responsibility. I can’t blame anybody for any aspect of what’s going on at the moment. Because we’ve been maniacally controlling as much of it as we possibly can. I get faxes and shit, adverts for American magazines to approve and schedules and blah blah blah.

But you must have had a sense that you could do it, because you recorded Lucky in five hours.

Yeah, and it was constantly trying to get to that… we get incredibly bored incredibly fast, but also we respond to a moment really well and then can’t ever do it again, forever after that it’s a cover version. That’s what we discovered with No Surprises. It was the first thing we recorded. We’d bought all this gear, literally the first time, everything was plugged in, pressed the red lights and… that was No Surprises, and the take on the album is exactly how we did it bar a few fixings. But we did six different versions of it afterwards going, “Ooh but that bassline’s not quite right and, ooh this that and the other.” Fucking anal. But we went back to the first one because we discovered in the recording process that the whole thing’s about the moment and fuck whether there’s mistakes on it or not.

What gear did you buy in?

We just said to Nigel, write out a wish list of everything you could possibly want and we’ll go and buy it. And we did. It’s all in flight cases. Lights go on and shit. Lots of old stuff, lots of new stuff. It cost the price of a large house in the countryside. Which would have come in handy to put it all in. I think he thought we were fucking mad. You know [Stop The Cavalry singer] Jona Lewie? We bought this incredible old plate reverb off him, this huge old box that broke every time we moved it. That cost a fortune, but everything went through it.

They’re very atmospheric songs, though, aren’t they? They rely on the spaces as much as the structure.

Yeah. We were listening to Morricone and Can and lots of stuff where they were really abusing the recording process, and we wanted to be involved with it but it was always at the point of complete ignorance. Like we’d be standing in front of some beautiful digital delay and going (makes manic knob-twiddling motion and accompanying noise) and Nigel’s going, “Oh fucking hell”, and suddenly everyone goes, “Yeah, that sounds great.” It’s children with toys. You don’t really know what the fuck’s going on but you’re digging all the lights…

How do you write? Do you come in with complete songs or are they worked on by the group?

They’re worked on. I’ll come along with something or Jonny will come along with something but it’s basically chaos a lot of the time.

Is it more democratic than it used to be?

Yeah, absolutely. Well, it’s always been like that to some extent. We did lots of rehearsals and changing things around, only because we had time. We had too much time, I’m sure we could have got it together earlier.

How long did it take altogether?

A year.

How are people going to consume this record. It’s not something you’d put on for a laugh is it?

Well, no. When we started I really wanted to make a record that you could sit down and eat to in a nice restaurant, a record that would go on and be cool and be part of the furniture. But I think there’s no way you can eat to this record! You have to sit down and stop doing whatever you’re doing.

What can you do to this record?

You can travel. You can sit on a plane. You can probably drive to it. I don’t think you can really do the housework to it.

The Tourist is a great song. It seems to be about fear of, or yearning for, solitude. It reminded me of a space walk.

Really? Wow, cool. You can make the video! To me it was… I have days where my mind is going so fast, it’s going as fast as the microwave or the car or the television waves, and it’s going so fast you just can’t control it and it’s in a lock and it’s just going to go forever. And The Tourist was like a sort of prayer to stop it happening. [MOJO discovered subsequently that The Tourist was mostly written by Jonny Greenwood.]

Is there a key song on the record, one that when you’d written it formed the mood of the record?

Exit Music. Lucky as well. That was like, “Fucking hell, woah, what was that?”

You did that in a hurry, didn’t you?

Yeah, we did it in five hours and I took it home and played it and cried. I thought, “Woah,” and I think it was because we’d been on the road for a while and we were really comfortable with each other and it just really expressed an excitement and happiness that we felt. It was written around the time that we first met R.E.M. and everything was changing shape and it was really exciting and terrifying. Exit Music was the first performance that we recorded that I thought every note of it makes my head spin, makes me really happy.

That was done for a commission, too [for Bax Lurhmann’s film Rome + Juliet].

And that was great it forced me to get my arse in gear and forced us to finish it because they were holding back the film for us to finish. It was, “Fuck, we’ve got to do it now, right now.”

Do you ever get that feeling. Fuck, I’m in this great band, doing what I want. The dream came true!?

Yeah. (Laughs) That’s why I wrote Lucky. It really was. We’re in this band, fuck everybody else and this is amazing. You pay for it, though.

What sort of fame is it at the moment?

It’s cool. I changed my haircut at home and nobody bothers me and I haven’t been anywhere else yet.

Someone recognised you over there just now. They’re all having a look.

Really? Oh well.

Now you know people like R.E.M. do you get fame lessons from them?

Yeah, they give us fame tutorials. No, while we were making this record I was having a love/hate relationship with the thought of fame and it was good that we knew people like R.E.M., I think we’d always been convinced that basically, that thing [of being in a band] lasts a couple of years and then it’s over. That was always a source of extreme depression to us, that’s the British tradition, that’s what British bands do. Over the period of a month we met R.E.M. and Elvis Costello and just to meet him – he was really nice, just to stand in front of him and talk to him was enough for me, it was like a major step, a closure of a certain thing. I can’t explain it properly, but it was empowering and then to go on tour with R.E.M. and see people who were really into music still after all this time and after all this bullshit and it chokes you.

Do you ever worry about the limits of the form, wish you could do something other than songs?

During The Bends I think I did. I felt I had to be like a tortured artist and I don’t feel like that anymore and it’s fantastic. Also I got into other things and not just being 100 per cent a tortured musician blah blah blah and being part of what’s going on.

I get really nervous when… Pop songs to me will always be the most powerful way of saying anything. I’ve got no intention of doing fucking aural soundscapes or whatever, it’s not gonna happen.

What are your touchstone songs? The ones that do it for you every time?

I’ll Wear It Proudly, Elvis Costello; Fall On Me, R.E.M.; Dress, PJ Harvey. On and on. . .

What do you always look for in a song?

(Huge pause) You have to stop listening to other people’s music when you’re making a record because you get really confused. You have to limit it. So when you finish it, everything you pick up you just fall in love with. You fall in love with music again in the most amazing way. We come off the stage to Prince Buster at the moment because that’s pop music, mindless but great. A Day In The Life, actually. I always find myself referring to that, at odd moments.

There’s an element of that song’s atmosphere about your stuff… Things changing fast, quite violent mood swings. And the line about “he blew his brains out in a car”, and the way that Lennon reported like a witness in that song. Is that the way you feel you’ve been writing on this record?

Yeah. Stuff like “I read the news today”. A lot of it was that approach. I’m standing here and I’m watching it but I’m going to write it down, that’s the only way I can deal with it. I’m not even going to say anything about it, I’m just going to write it down.Electioneering, for example, what can you say about the IMF, what can you say about politicians? You just don’t, you just Write It Down.

When do you tend to write? What state are you in?

Agitation or panic. Paranoia or…

Two in the morning?

On trains, walking around, on home it’s been everywhere. The Bends was less like that, it was some guy on the back of a bus getting drunk and feeling really quite upset! This is much more simply absorbing what’s around when it has been most potent. Two in the morning on trains, whatever.

Who are the singers you look out for?

Scott Walker, Michael Stipe and Elvis Costello. He’ll go for singing in a completely neutral, detached way to being really violent and you can’t tell if he’s into it, and then he is into it and it’s really alarming. PJ Harvey’s the same. She’ll deliver a song and then switch.

How much acting do you do on-stage? It’s part of a singer’s job to act, isn’t it?

Yeah. I’m not that good an actor. That’s why it’s quite good when, say, Jonny’s flailing around, ’cos I just stand there and wait until something happens. Some nights you think, “I can’t sing this ’cos I can’t act tonight.” It’s the same with recording, that’s just part of performing. You’re not going to feel it all the time. That’s why I wrote Bones.

Are you all getting on well now?

Yeah. It’s cool. We argue all the time, as people do when they have to spend a lot of time together, but it’s fine.

There was a lot of strain during The Bends?

Yeah, but it’s not like that now. We all dealt with all this bullshit in different ways and then resolved it and we’re a little bit wiser now.

I think audiences are ready again now for non-mosh music.

(Animatedly) It’s about fucking time, really! I think when Offspring came out the bubble had burst for me. Seeing that video with all those macho guys, all these incredible pecs and stuff, banging into each other in slow motion, this so-called aesthetic, and to me it was fucking disturbing and mindless and really horrible.

What was sweet about last night’s crowd they were prepared to go with whatever you played. How are you going to manage that at Glastonbury?

Aargh. We’re just providing the music. “Hi everyone! We’re here to play you some music for an hour and a half and that’s it.” It’s a festival and we’re one of the bands on.

Are you are control freak?

Yep.

Are the rest of the band control freaks as well?

Yeah (laughs).

Are you the control freakiest?

Yeah. Most of the time it’s fine but occasionally it gets to you and it’s fucking horrible. But I want to do it like this. I don’t care what anybody says, I don’t care about worrying about burning myself out because I just feel like I have to do it, it’s too important.

Do you know what you want the next record to be yet.

I’ve no idea. It’s good, actually, because I’m not thinking about it. With The Bends we immediately went off and started doing new stuff but with this I think there’s just going to be a time where we breathe a few sighs of relief.

-

READ MORE: Thom Yorke’s Tour Diary: “All I want to do is run around waving my hands up and down like Björk.”

Three weeks after Barcelona, OK Computer received its UK release and shot straight to Number 1. In America, the story was slightly different; the album entered the Billboard 200 at Number 21, then dropped down the chart. It was a disappointing showing when you consider that The Prodigy’s Fat Of The Land crashed straight in at Number 1 in the Billboard chart that same week. It was, however, an improvement on The Bends, which stalled at Number 88, but not quite what Capitol had hoped for. Let Down, released as a promotional single in the US, also proved to be an, er, let-down.

“To be perfectly honest, I think the jury’s still out on this record in terms of radio,” said Nic Harcourt, programming director at radio station WDST in Woodstock. Indeed, Lisa Worden, at the hugely influential KROQ in LA, says the station loves Radiohead but confesses, “I don’t know yet if I hear any radio smashes.”

“When I first heard the album I thought it was a little self-indulgent, but then, as the complexity of it revealed itself to me, I realised that it’s really well put together,” says Paul Q. Kolderie. “I think this music has a lot of beauty in it, a spiritual quality, and that’s what people are grabbing on to. In terms of the band’s commercial future, the negative factor is that Thom is going to shoot himself in the foot, although none of the others will. The positive factor is what they’ve got up their sleeves in terms of music – they have three or four smashes that they’re waiting for the next record to put out. The real breakthrough will come with the next one, and I think it’ll come out a lot quicker than you think.”

“There’s nothing I’ve seen in any country in the world that’s excited me as much live,” says Capitol’s president Gary Gersh. “There isn’t a better singer than Thom Yorke. Jonny is as exciting a guitar player as anyone alive. Our job is just to take them as a left-of-centre band and bring the centre to them. That’s our focus, and we won’t let up until they are the biggest band in the world.”

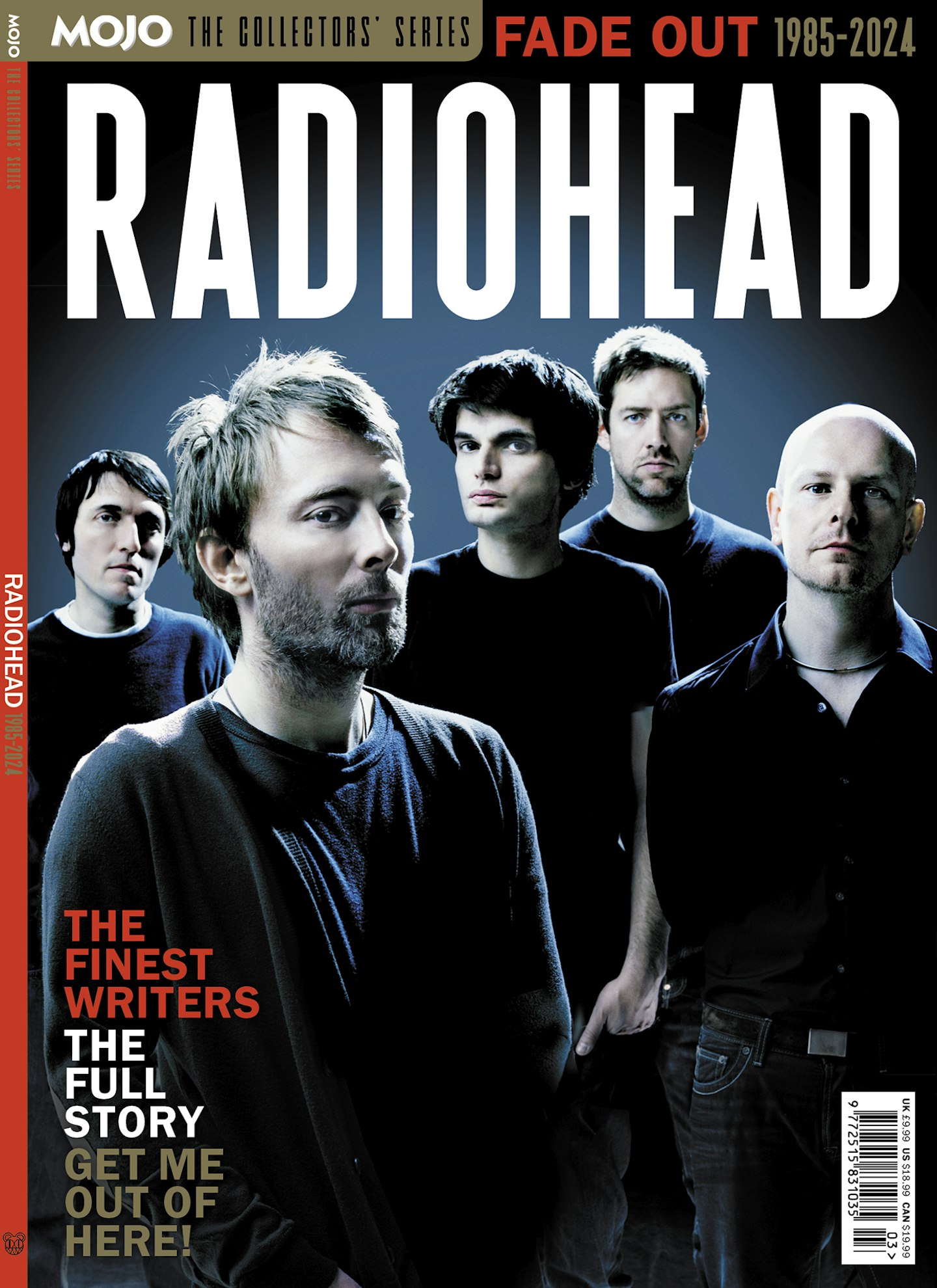

This feature appears in MOJO’s recent Radiohead special, MOJO The Collectors’ Series: Radiohead Fade Out 1985-2024. More info and to order a copy HERE.

Radiohead 2025 European Tour Dates:

11/04 – Madrid, Spain, Movistar Arena

11/05 – Madrid, Spain, Movistar Arena

11/07 – Madrid, Spain, Movistar Arena

11/08 – Madrid, Spain, Movistar Arena

11/14 – Bologna, Italy,Unipol Arena

11/15 – Bologna, Italy, Unipol Arena

11/17 – Bologna, Italy, Unipol Arena

11/18 – Bologna, Italy, Unipol Arena

11/21 – London, UK, The O2

11/22 – London, UK, The O2

11/24 – London, UK, The O2

11/25 – London, UK, The O2

12/01 – Copenhagen, Denmark, Royal Arena

12/02 – Copenhagen, Denmark, Royal Arena

12/04 – Copenhagen, Denmark, Royal Arena

12/05 – Copenhagen, Denmark, Royal Arena

12/08 – Berlin, Germany, Uber Arena

Photo: Jim Steinfeldt/Michael Ochs Archives/Getty