After almost 40 years, 15 albums and a small library’s worth of column inches, the Manic Street Preachers are an established feature of British rock landscape. Indeed, it’s easy to mistake their presence as an inevitability. Long before their narrative’s traumatic fissure – the disappearance of Richey Edwards in February 1995 – the Manics seemed predestined for ephemeral glory at best: their early gigs were 20-minute exercises in “hate-noise”, while initial singles scrambled pop art and politics with punk’s Situationist rhetoric into barely coherent blasts, culminating in the self-immolatory brilliance of Motown Junk. They promised to make a million-selling debut album and then break up. Inevitably, real life got in the way.

Coming of age in the ’80s amid south Wales’ embattled mining communities, the original quartet were bonded by shared experience and family ties: cousins James Dean Bradfield (guitar, vocals) and Sean Moore (drums) drove the music, while Edwards (brain, notional guitar) and Nicky Wire (bass) wrote lyrics and manifestoes, initially much inspired by Wire’s brother Patrick, who inculcated appreciation of poetry and heavy metal in his younger sibling. The challenge for Bradfield and Moore was to sweeten their friends’ voracious intelligence for mainstream consumption. This they achieved fitfully across 1992’s debut Generation Terrorists, but it wasn’t until 1996’s million-selling Everything Must Go that the masses finally submitted. Vindication would be tempered, of course, for by then Edwards was gone – though not before his molten visions had dictated The Holy Bible, the band’s enduring masterpiece.

Reconciling commercial success with iconoclastic instincts has proved fraught at times, and the ’00s were characterised by self-doubt, assuaged somewhat by 2011’s landmark singles compilation National Treasures, which featured pivotal non-album tracks Motown Junk and The Masses Against The Classes. Yet however much their past defines them, 2014’s brilliant Futurology proved the Manics Street Preachers’ history also shapes their ongoing fascination with the art of rock’n’roll. With yet another career high point arriving earlier this year in the shape of 15th LP, Critical Thinking, to paraphrase their original catalytic blueprint The Clash: this future remains unwritten. Here for now, though, is their past laid out in all its glory…

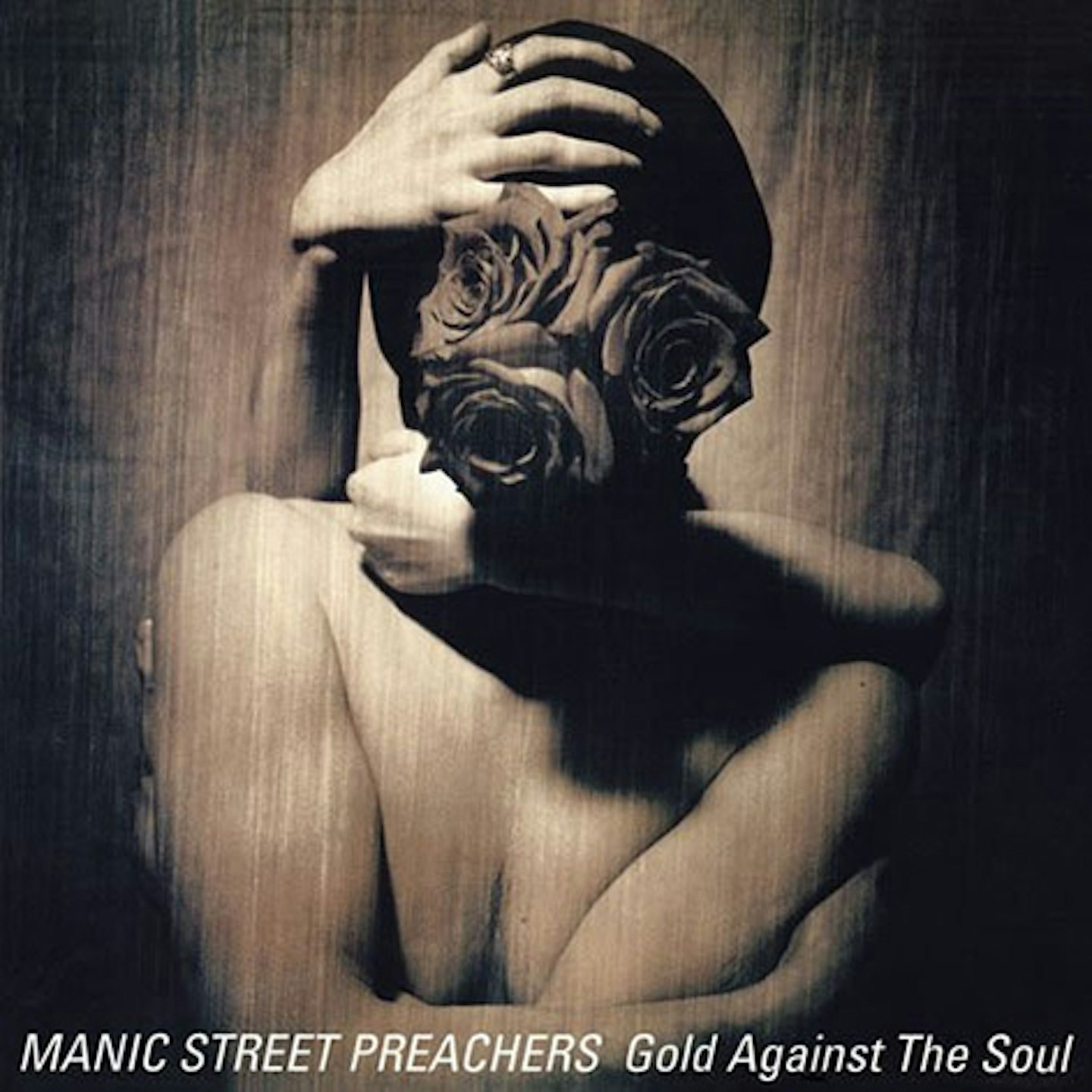

15.

Gold Against The Soul

Columbia, 1993

The Manics’ second album was the muddled response to the conceptual misfire of Generation Terrorists. A shallow reservoir of material compounded the questionable logic of spending months with rookie producer Dave Eringa at Hook End Manor, an expensive residential studio formerly owned by David Gilmour that Nicky Wire would subsequently describe as “a hollow arena to make arena rock”. Yet the chastened mood and arid sonics couldn’t entirely quash the power of the band’s maverick instincts: brilliant instances of alchemising glory out of gloom, From Despair To Where and La Tristesse Durera (Scream To A Sigh) are setlist fixtures 30 years on, while Eringa remains the go-to MSP producer.

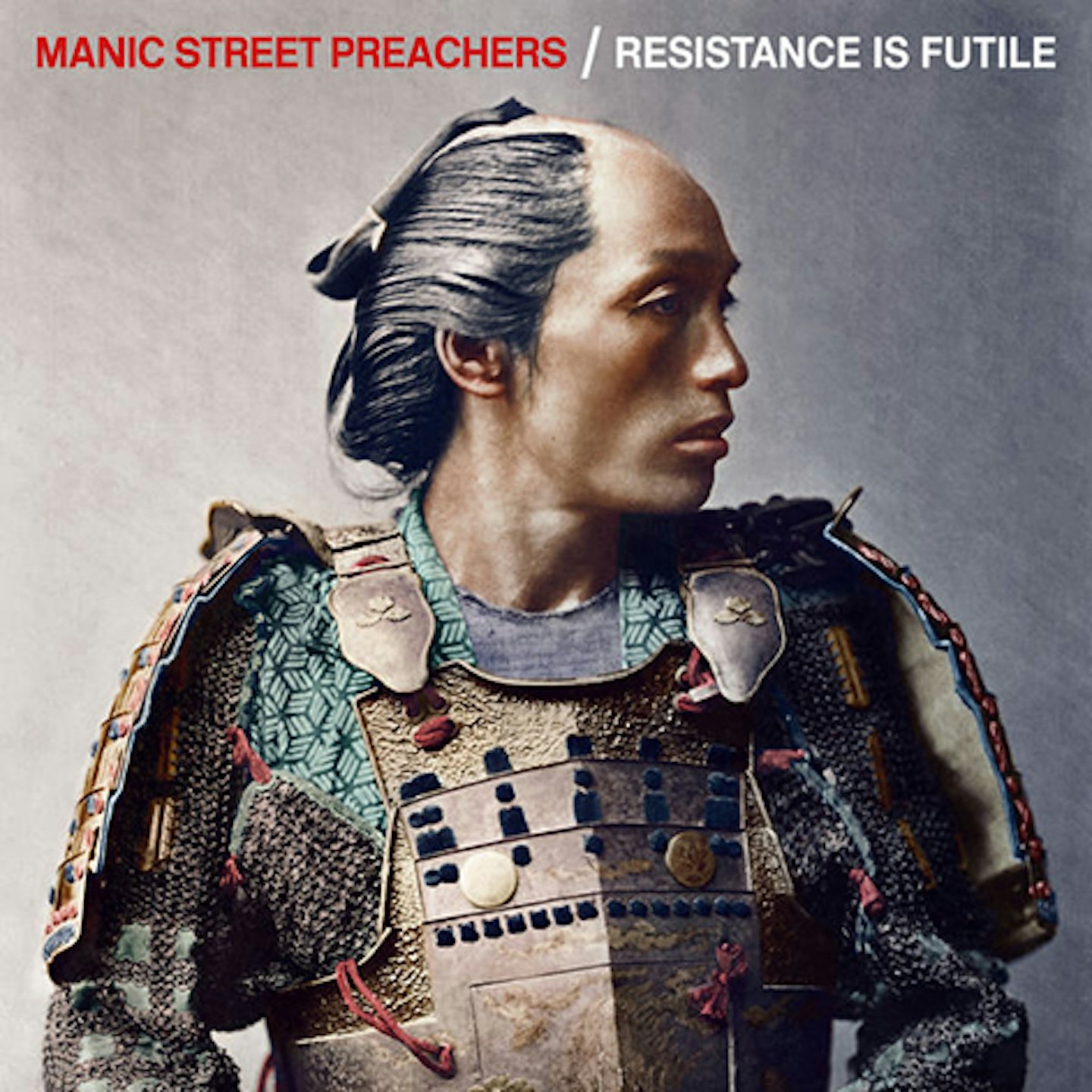

14.

Resistance Is Futile

Columbia, 2018

The title of a B-side from the period, Holding Patterns, could apply to the 13th Manics album as a whole. Creatively distracted by real life family concerns, the band’s musical engine compensated like a cyclist furiously shuffling gears through rocky terrain, finding relief in familiarity. Jewels lay amid the broad brush strings and big choruses: International Blue’s propulsive hymn to artist Yves Klein; Distant Colours’ regretful allegorising of political malaise as mid-life crisis; Dylan and Caitlin Thomas’s tempestuous marriage adapted into a Fleetwood Mac-style duet between Bradfield and The Anchoress. The poignant Nicky Wire-sung The Left Behind, meanwhile, was a dignified finale.

13.

Rewind The Film

Columbia 2013

The Manics closed 2011 by playing all 38 of their singles at London's O2 Arena, amid reports that this marathon act of retrospection would preface a radical overhaul in modus operandi. Yet beyond the obvious – a predominance of acoustic instrumentation; Bradfield sharing or ceding lead vocals on a couple of songs to Richard Hawley and Cate Le Bon – Rewind The Film sought nourishment in home comforts: Welshness and Wales are specifically invoked on the first two songs and insinuated throughout the band's gentlest, most unaffectedly beautiful record. Essentially an act of retrenchment rather than a revolution; that came with the contemporaneously hatched Futurology.

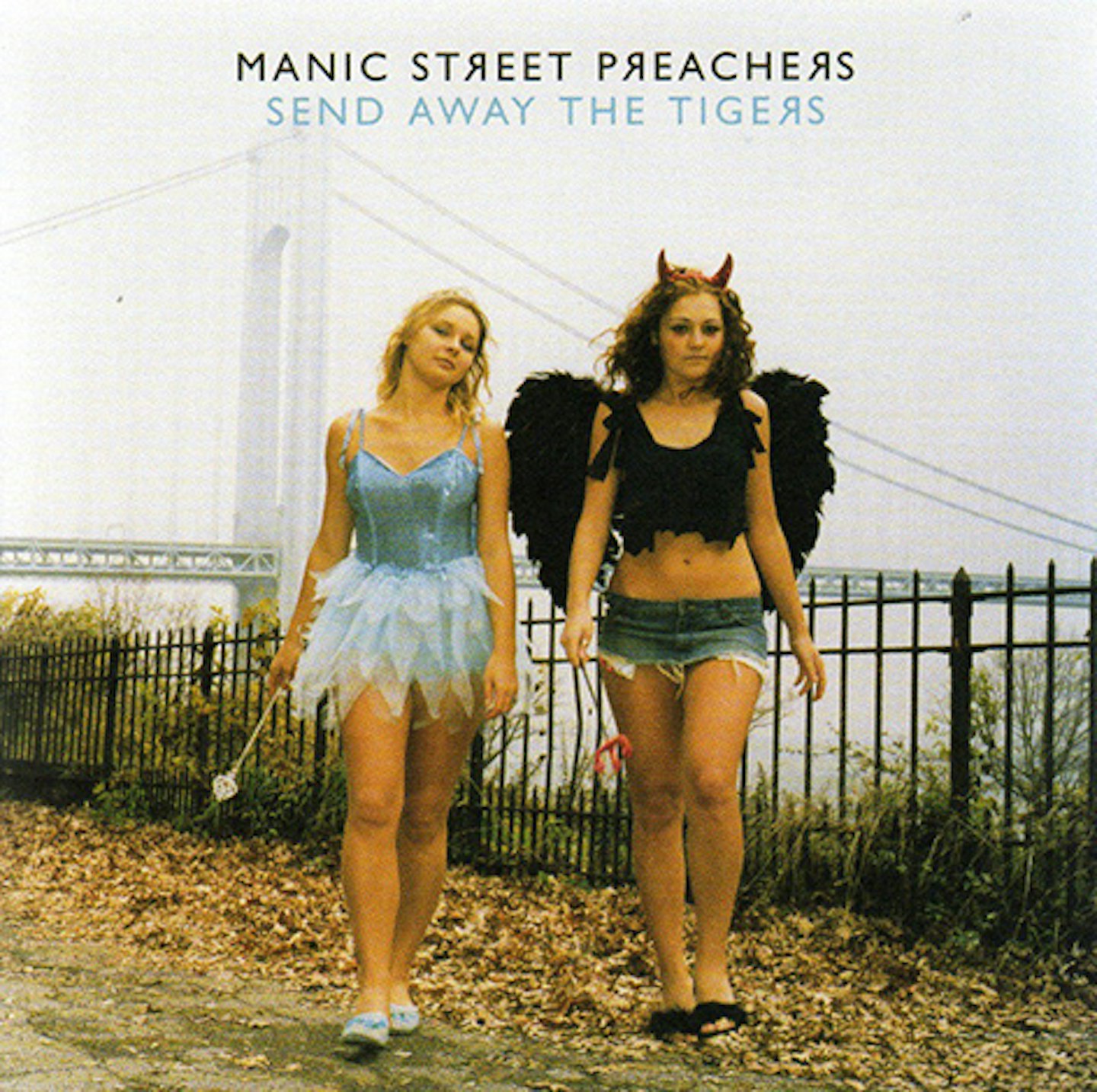

12.

Send Away The Tigers

Columbia, 2007

Shaken by Lifeblood’s weak chart numbers, the Manics effected one of the great tactical retreats, proving that artistry and pragmatism need not be incompatible. The basic premise was Everything Must Go’s anthemic templates given an adrenalin shot, but any sense of calculation was dispelled by the performances’ cavalier intensity. Even its more preposterous moments (Autumnsong nearly becomes Queen) felt valid, while the title track was a restorative declaration of core values (“I was born to underachieve”) and the Nina Persson duet Your Love Alone Is Not Enough soared on the wings of Elysian melody.

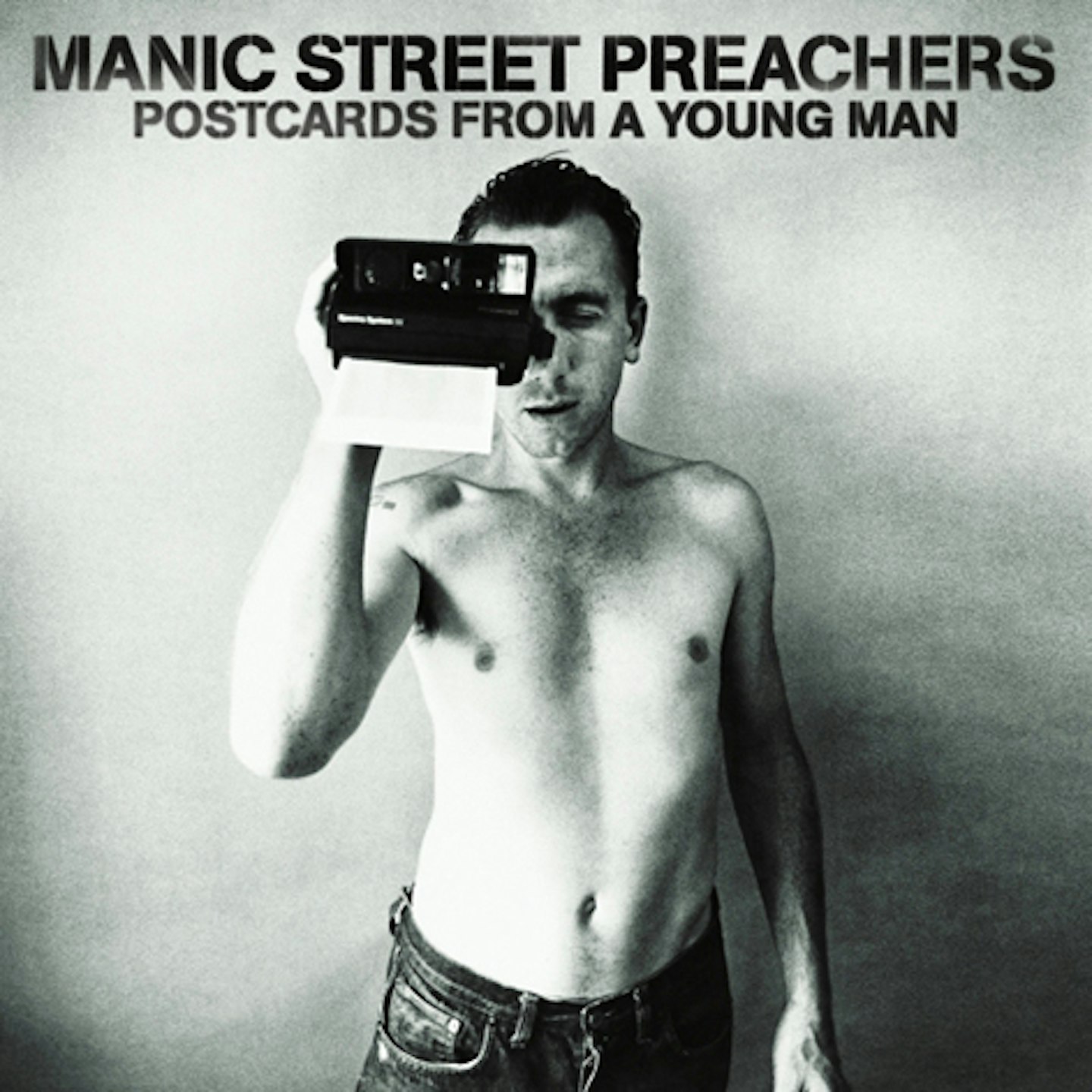

11.

Postcards From A Young Man

Columbia, 2010

Having honoured the departed Richey Edwards with Journal For Plague Lovers, only the churlish could begrudge its successor's rather more luxuriant schemes. An array of Manic heroes – John Cale, Ian McCulloch, Duff McKagan – joined orchestra and gospel choir to deliver the anthemic overload demanded by this self-proclaimed “one last shot at mass communication”. At least the band’s ensemble chops were in almost perfect communion with their commercial antennae. Subversion lurked beneath the super-sleek veneer: A Billion Balconies Facing The Sun quoted JG Ballard’s Cocaine Nights, while Britain’s post-industrial vacuum was righteously skewered on All We Make Is Entertainment.

10.

The Ultra Vivid Lament

Columbia, 2021

Proof that the Manics thrive in winter (“it brings us closer together,” averred Masses From The Classes), The Ultra Vivid Lament’s beautiful hibernal tones created a psychic landscape cloudy with confusion and self-doubt – “My complicated illusions are now no more than faith” – out of which the group drew their most subtly transcendent music. While Orwellian and Don’t Let The Night Divide Us wove insidious political commentary into Abba-esque arrangements big on the ol’ Joanna, opener Still Snowing In Sapporo and Diapause were classic examples of the Manics yet again finding fresh energy in their greatest influence: themselves.

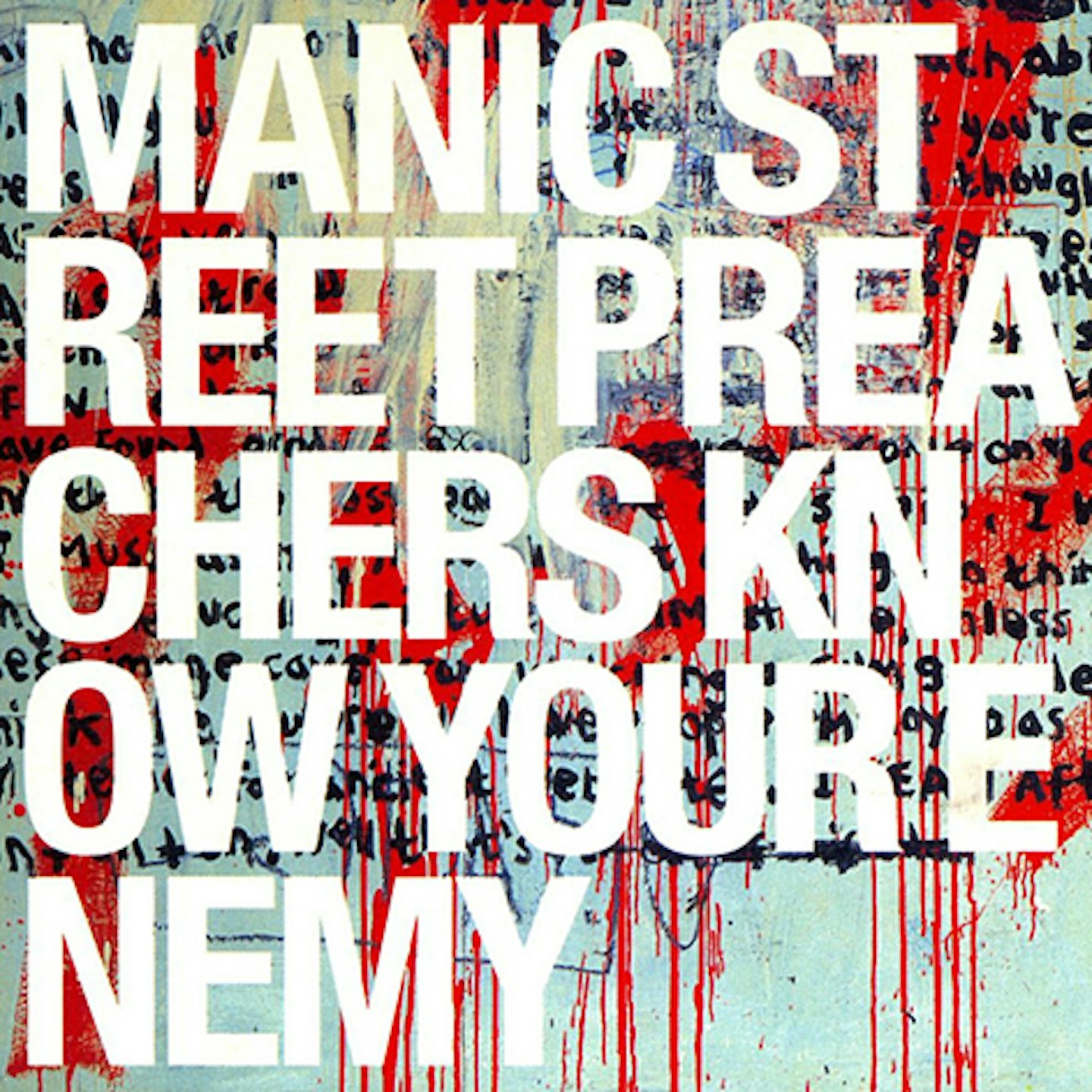

9.

Know Your Enemy

Epic, 2001

The Manics followed up the soft focus anthems of This Is My Truth…, by delivering this sprawling, skewed equivalent of Sandinista (2022’s reissue restored its original concept of thematically distinct twin albums), or In Utero, a record designed to confound its audience and reassert its authors’ contrarian values. Schizophrenically attired – now they’re Spector/The Fall/Stereolab/R.E.M./Sonic Youth – amid its scruffy production values, random noise bursts and Nicky Wire’s debut lead vocal, Know Your Enemy featured a clutch of spectacular compositions, none greater than Epicentre or The Convalescent, a scything motorik navigation of Wire’s pluralist culture map: from Picasso to Payne Stewart, Juantorena to Srebrenica. Uneven but underrated, and consistently rewarding.

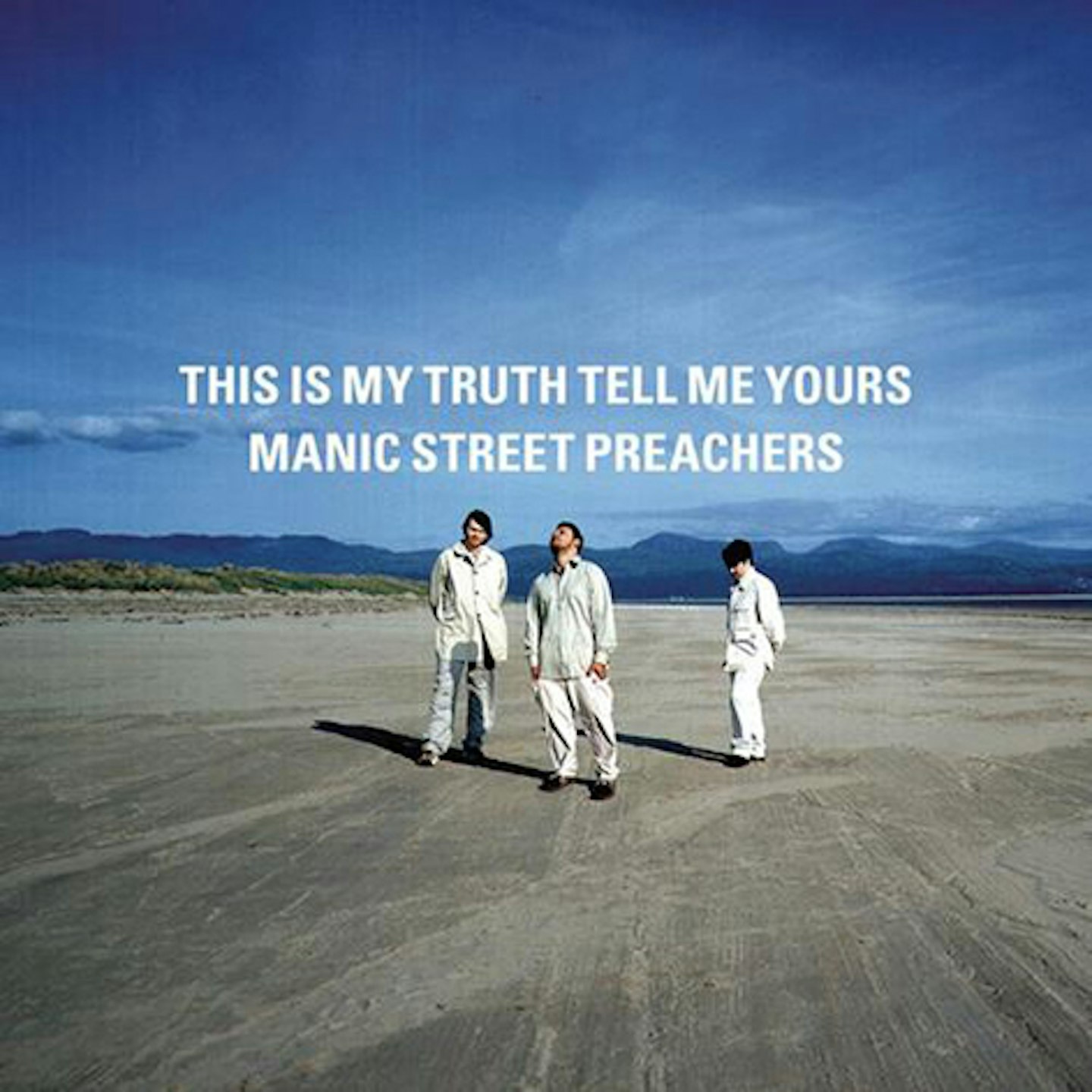

8.

This Is My Truth Tell Me Yours

Epic 1998

At last successful, yet bereft: ambivalence at their new status seemingly bled into the sleeve image of Everything Must Go’s follow-up: while Nicky wearily and Sean suspiciously eye the sands on a Welsh beach, James raises closed eyes to the heavens. The music was likewise passive, overwhelmingly dejected: If You Tolerate This Your Children Will Be Next beautifully hymned the International Brigades from a pacifist’s guilty perspective. The Everlasting yearned for an innocent past “when our smiles were genuine”. Relegating Prologue To History’s uproarious cultural dissertation to a B-side made no sense (it was added to the revised track listing of 2018’s reissue) but This Is My Truth... nonetheless delivered the band’s first Number 1.

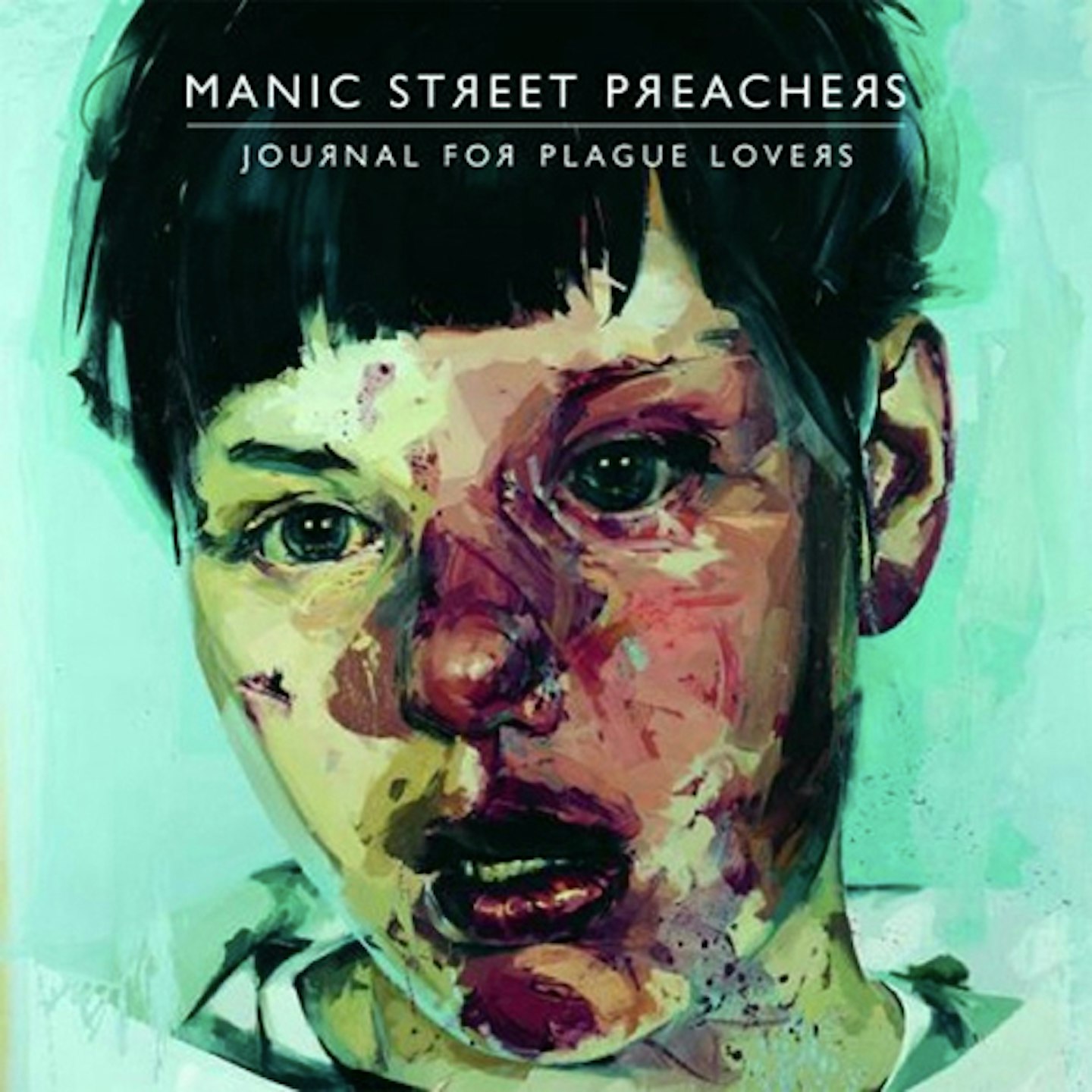

7.

Journal For Plague Lovers

Columbia 2009

Post-millennium blues duly dispelled by 2007’s Send Away The Tigers' heartland holiday, the Manics felt sufficiently resolute to deal with the ideas Richey Edwards had presented them shortly before his exit. Reuniting with their friend brought heightened intensity, amplified by Steve Albini's verité recording ethic, and caustic powerage like nothing since The Holy Bible. But Journal For Plague Lovers was no mere retread: the likes of Me And Stephen Hawking and Virginia State Epileptic Colony evinced humour, two oft-overlooked Richey qualities, while right to the final quavering vocal on William's Last Words, this powerful nuanced exercise was surely what he would have wanted.

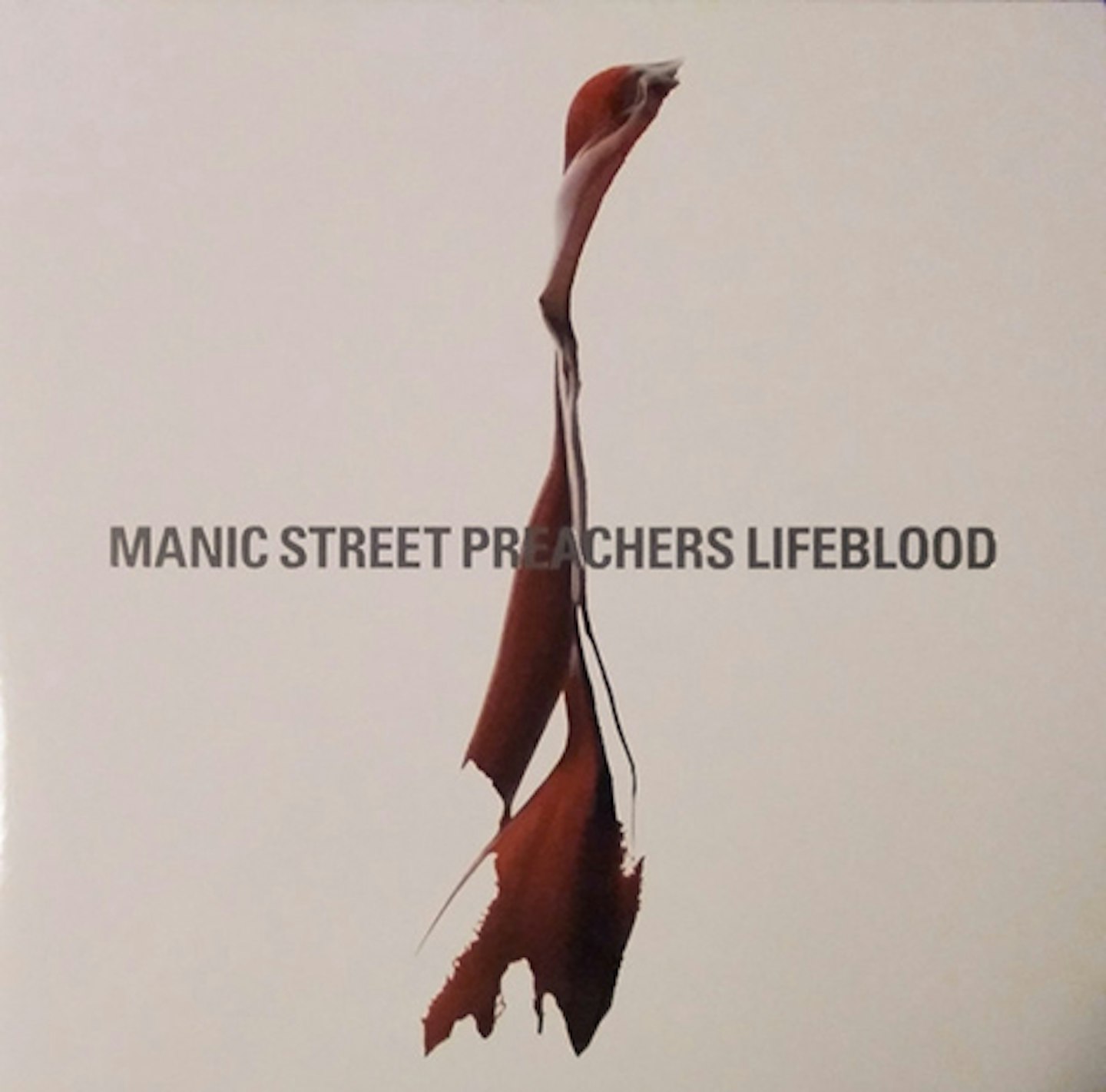

6.

Lifeblood

Columbia, 2004

Equally underrated – not least by the band themselves – Know Your Enemy’s follow-up never quite got over the wall of mystification that greeted its first single The Love Of Richard Nixon, a retro-futurist song of empathy for the disgraced former US President. Yet the messed up 21st century world has caught up with Lifeblood, a record whose glacial textures and contradictory perspectives sound utterly of the now. With ghosts lurking at every turn, here are some of the Manics greatest anthems to doubt and loss – A Song For Departure; Empty Souls – while 1985 and Cardiff Afterlife were euphoric opening and closing soundtracks to this uniquely melancholy story.

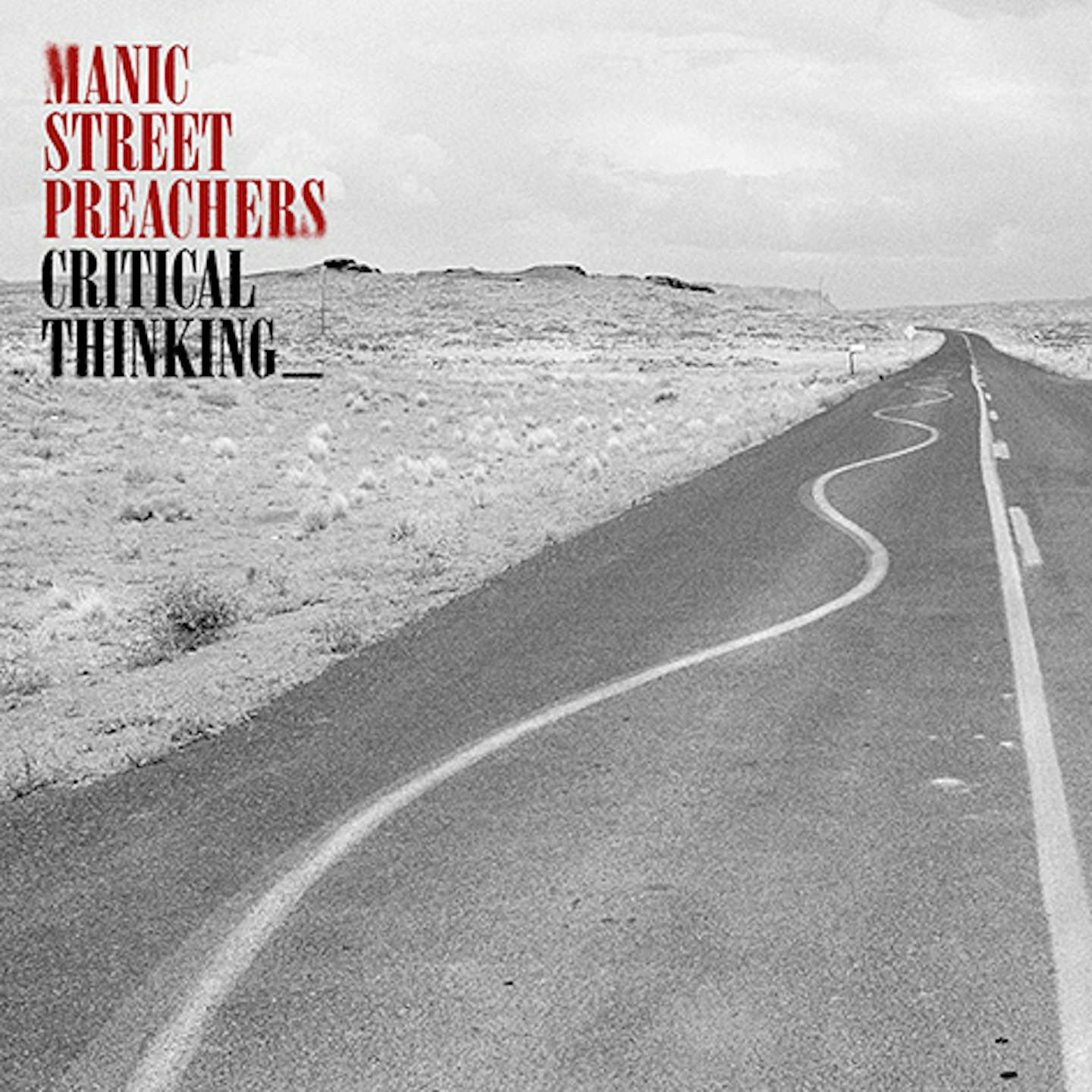

5.

Critical Thinking

Columbia, 2025

On album 15, the Manics found new ways to be different yet still themselves, with typically abrasive vigour. Hallmark misanthropy gets an art-eco twist (People Ruin Paintings); digital utopias are demolished (Deleted Scenes); an admission of mid-life irrelevance is turned into a jubilant vehicle for carrying on regardless (Decline & Fall); while the title track skewers the banality of contemporary discourse via Nicky Wire’s J.G. Ballard-referencing sprechgesang. The band’s ’80s touchstones sparkle and shine so hard, yielding career peaks in Bradfield’s Brushstrokes Of Reunion and Wire’s Hiding In Plain Sight. Behold, a new model Manic big music.

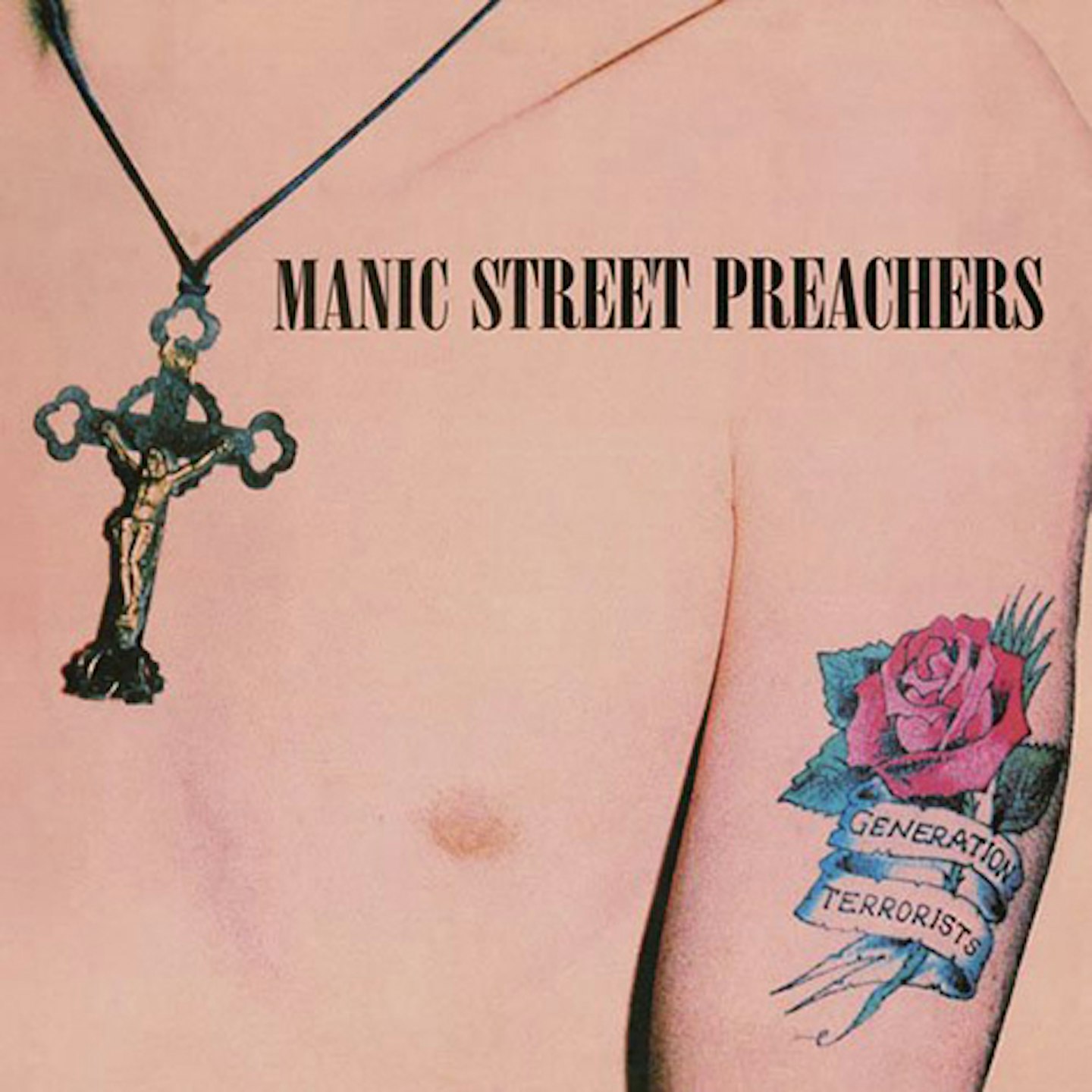

4.

Generation Terrorists

Columbia 1992

Self-ordained to be a 16 million-selling one-off game changer, the mythic status accorded in advance to the Manics’ debut guaranteed it could never possibly deliver. Yet especially now, far from the hubbub of the era’s contentious rhetoric, Generation Terrorists feels surprisingly robust. Steve Brown’s steroidal arena rock production, programmed drums et al, is the perfect conduit for scrawny punk hissy fits (Repeat) and Marxist hair metal (Slash ’N’ Burn) alike, while he believed in his young charges sufficiently to nurture their elegiac gene, revealed to timeless effect with Motorcycle Emptiness. Overlong, but even the excess baggage is necessary in building a complete profile of these beautiful and damned provocateurs.

3.

Futurology

Columbia 2014

It’s quite a feat for a band to effect a reinvention on its twelfth album, and not the least of Futurology’s qualities is how unlike the Manic Street Preachers it often sounds. Essentially succeeding where 2004’s Lifeblood narrowly failed, here was the European art-pop synthesis these admirers of David Bowie and Simple Minds felt they owed to their fanboy selves (Europa Geht Durch Mich; Between The Clock And The Bed), while amid the bleached modernist textures lay a pulsing heartbeat, thanks especially to Bradfield's deep-wrought emotional delivery inhabiting the songs’ meticulous constructs and unerring melodies. Both evocative and unprecedented: a tantalising augury for what might yet come.

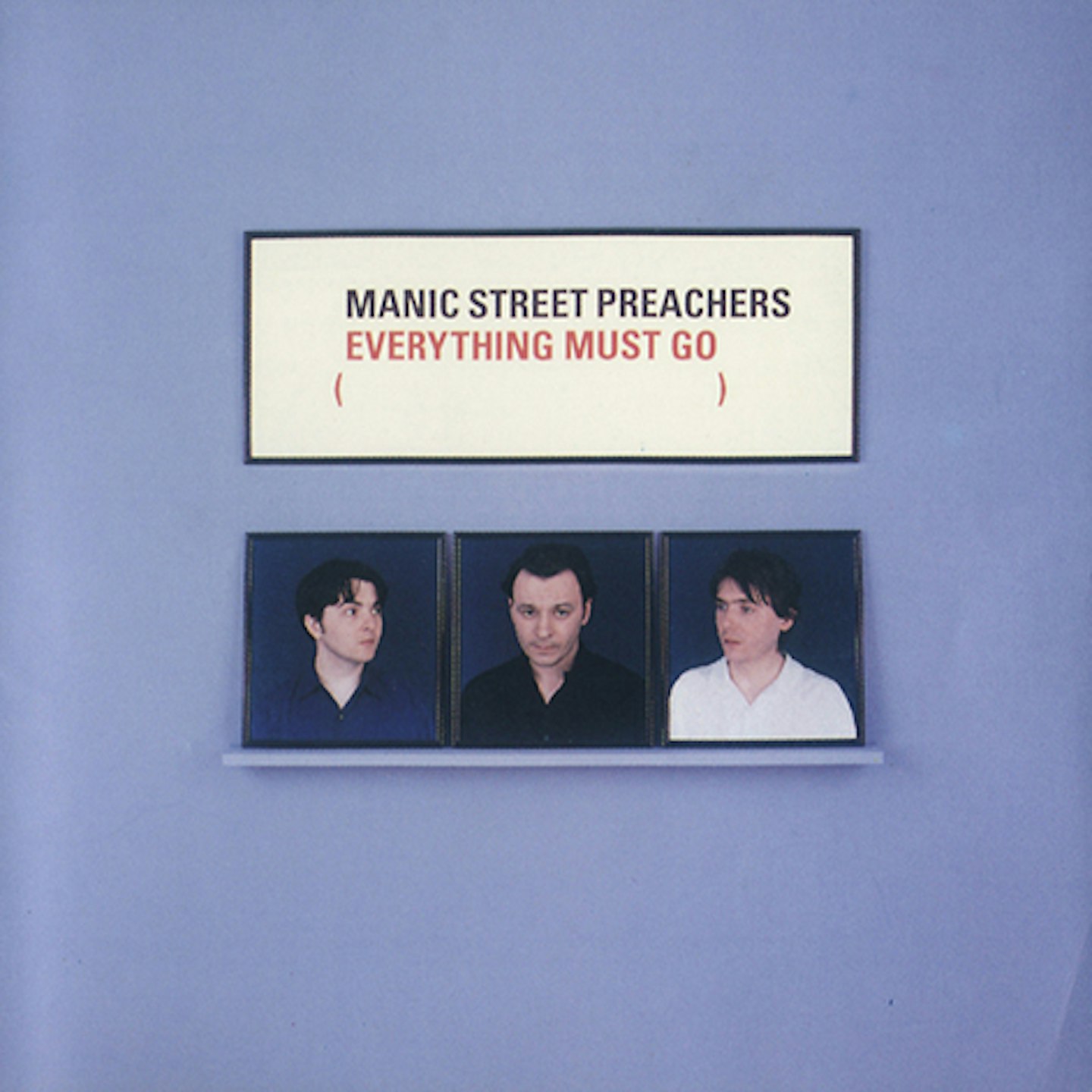

2.

Everything Must Go

Epic 1996

Released at the apex of Britpop, the Manics’s fourth pulled the trick of superficially tuning into the era’s nostalgic gratification while in realty pursuing a very different agenda. “What’s the point in always looking back, when all you see is more and more junk,” noted No Surface All Feeling. That song was one of five featuring lyrics by Richey Edwards, whose absence impelled a stylistic reconfiguration around Nicky Wire’s sparer lyrical style, honing melancholic, string-soaked songs of praise to the lost and alone, none greater than the working-class elegy A Design For Life. Populist yet dignified, Everything Must Go was a remarkable achievement, regardless of context.

1.

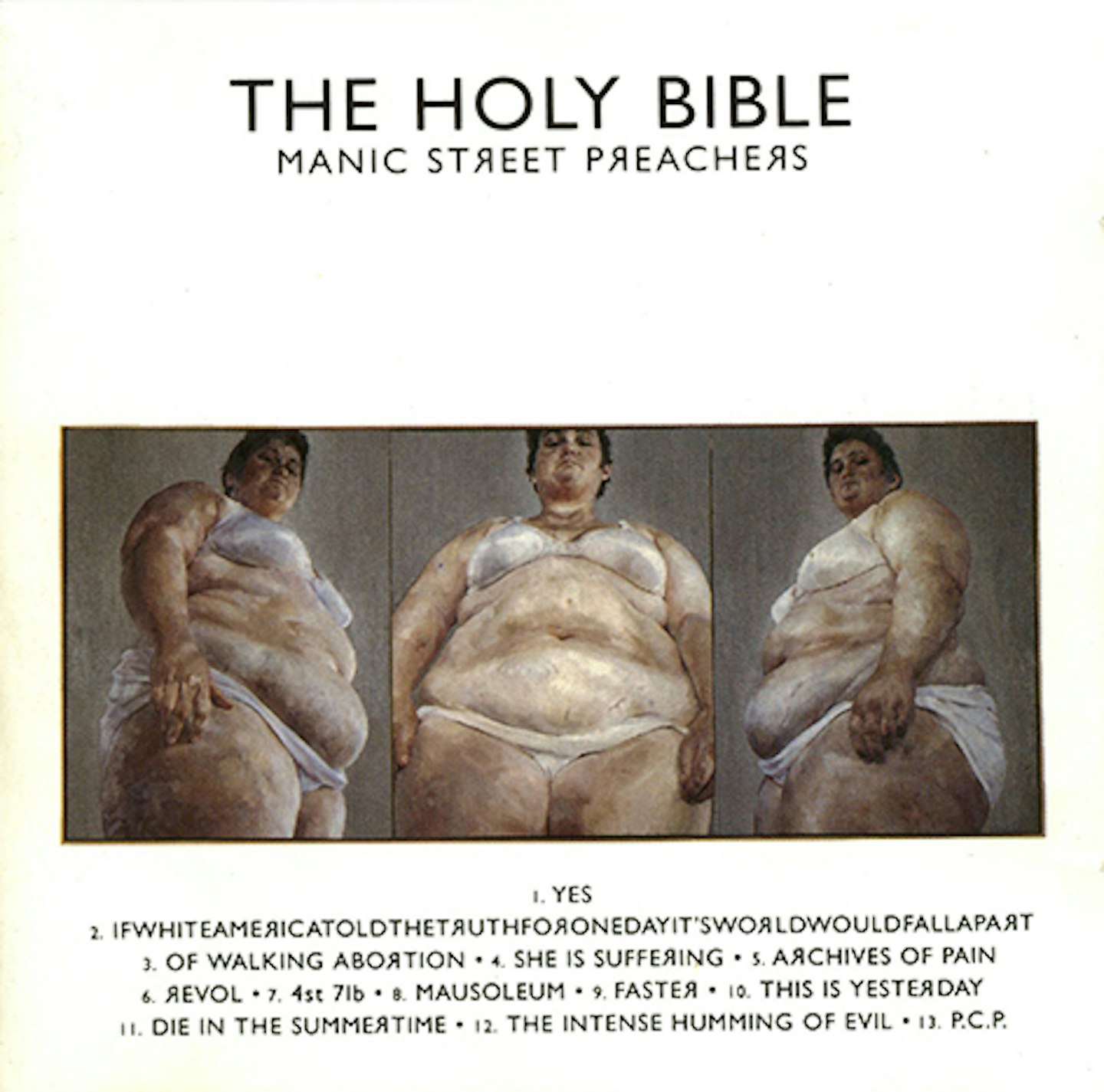

The Holy Bible

Epic 1994

Subsequent events inevitably framed The Holy Bible as Richey Edwards’ pre-ordained valedictory. Yet that reading conflicts with the euphoric mindset of its creation. Disdaining the expensive gloss applied to little avail on the preceding Gold Against The Soul, the Manics recorded cheaply in a Cardiff backstreet, the tiny studio a perfect conduit for the songs’ astringent yet minutely detailed post-punk designs. While Edwards hyperventilated at humanity’s callous instincts (Mausoleum; The Intense Humming Of Evil) and dissected his personal traumas in harrowing detail (4st 7lbs; Die In The Summertime), the music channelled a collective shedding of inhibitions. As Faster defiantly declared: “I know I believe in nothing but it is my nothing.”

Photo: Martyn Goodacre