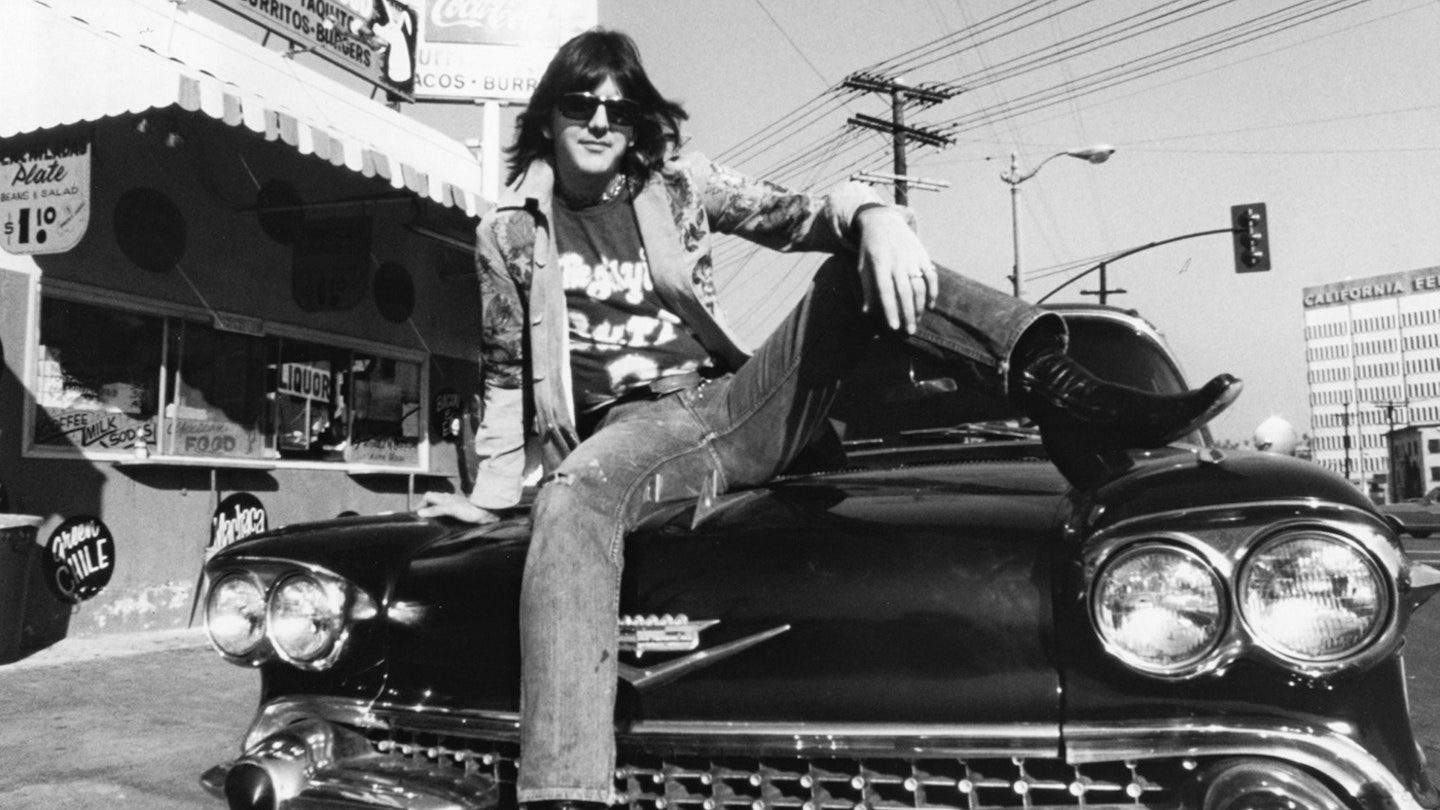

Fifty one years ago, Gram Parsons passed away aged just 26, but not before two solo albums, rich in country soul, fulfilled a portion of his promise. The tragedy and, perhaps, the inevitability of that loss is still felt by friends and fellow musicians. In this extract from MOJO’s 2023 feature on Parsons, his life and his music, Grayson Haver Currin charts the winding road that led to GP and Grievous Angel, a road that saw him jettisoning The International Submarine Band, fleeing The Byrds, going cold on The Flying Burrito Brothers and getting booted out of the sessions for Exile On Main Street…

BY MARCH 1972, GRAM PARSONS – 25, in Los Angeles for less than five years – was already unsure how he still fit into the music industry, or if he ever had.

“One of my problems is understanding the necessary business requirements for anything – wanting to ignore them… but knowing certain things are necessary to get anything happening,” he said that month during a discursive and narcotised conversation with Chuck Cassell, A&M Records’ communications head. (The full tape was released three decades later as Big Mouth Blues.)

“But I like the bright lights, and that’s part of country music,” Parsons opined. “The country guy in the big city, who doesn’t know where to go.” In just four years, Parsons had already bailed on three bands, including two of his own. Before LHI label boss Lee Hazlewood could even release The International Submarine Band’s Safe At Home, one of the first bona fide country rock records, Parsons was flirting with The Byrds, a band that had helped lure him to California but seemed on the verge of break-up itself.

In fact, when Byrds bassist Chris Hillman found himself waiting in a bank line alongside Parsons in early 1968, the eternal opportunist told him the ISB was already done. Hillman invited him to a Byrds practice that night. “He knew his way around our songs, and could sing, too,” Hillman wrote in his memoir, Time Between. “Keyboard player? Not really, but he more than made up for it with some songs he had written and brought in to play for us.”

Parsons’ five-month stint with The Byrds was pivotal for the band, himself, and the sound of rock at large. His deepening interest in country redirected a group on the cusp of cutting a heady concept album that traced music’s evolution through the 20th century. Hickory Wind, his paean to the bygone innocence of his Southern youth, became a linchpin for The Byrds’ country turn on Sweetheart Of The Rodeo. Much to the chagrin of the staid Grand Ole Opry, they played it by surprise when they became the first rock band to perform at country’s ‘mother church’, the Ryman in Nashville.

But by the time Columbia could issue Sweetheart, the band had excised most of Parsons’ vocals. They worried not only about potential legal entanglements with Hazlewood but also that it would misrepresent The Byrds, since Parsons stopped touring the moment The Rolling Stones showed up for their London gig at the Royal Albert Hall. He refused to continue to South Africa, insisting he was a conscientious objector to apartheid, though the band was playing there as protest.

“It wasn’t for political reasons. It was because he wanted to stay in London,” Roger McGuinn snapped in an inter view less than a year later. “He dug it there, dug Marianne Faithfull and The Rolling Stones. He wanted to stay in that scene.”

Parsons’ restlessness didn’t end there. By the time McGuinn inveighed against Parsons, he and Hillman had already reconnected as the Flying Burrito Brothers, playing lots of country and smoking lots of weed in Topanga Canyon. “Gram and I shared a common vision to bring real country music to a rock audience with a hip sensibility,” Hillman wrote. “We agreed it would make sense for us to join forces.”

The Gilded Palace Of Sin, the Burritos’ debut, was the scintillating culmination of everything Parsons had already done, with R&B and rock frisson tucked inside classic country ache. But Parsons couldn’t stay. He became convinced that Chris Ethridge was a great bassist who didn’t understand country and that ‘Sneaky Pete’ Kleinow was a pedal steel ace who wasn’t fit for the gig. He stuck around only long enough to make sure the second album didn’t become what he dubbed “a freak hit”.

For Jet Thomas, Parsons’ already evident lack of stickability was a familial legacy – a by-product of trust fund and tragedy. “He had too much money. That was one of his biggest problems. He didn’t need money, and everyone else around him did. They couldn’t afford to get drunk and not perform. He could. It was his way to cope.”

In the fall of 1971, after Parsons had overstayed his welcome at the Stones’ Exile On Main St. sessions in France, he rendezvoused with the Burritos in the South, sitting in with them in Charlotte and Baltimore. He was impressed by their new musicality, especially the alacrity of steel player Al Perkins and champion bluegrass fiddler Byron Berline.

“It was probably just a compliment,” remembers Perkins, laughing, “but he said, ‘If you’d been the steel player when I was in the band, we’d probably still be together.’”

Idle praise or not, the comment was telling. More than two years since his last real record, new music was on Parsons’ mind…

Photo: Getty Images

This article originally appeared in MOJO 359.