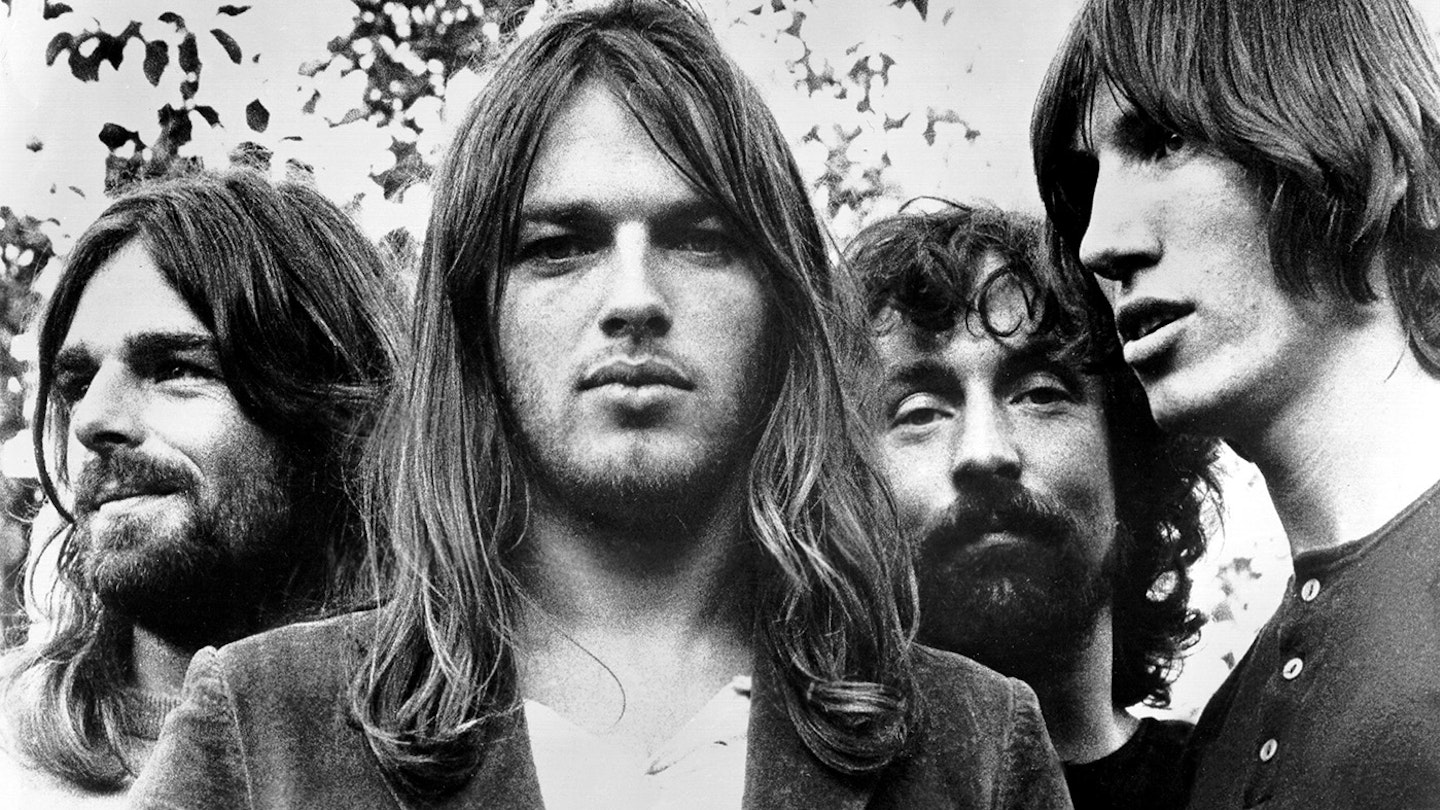

With Pink Floyd floating aimlessly in a post-Syd Barrett, cosmic hippie haze, in 1971 Roger Waters proposed a brand-new “philosophical and political” vision for the group. Within weeks, the peerless The Dark Side Of The Moon would start to take shape. MOJO's Stevie Chick charts the ascent of Floyd's masterpiece...

The first sound any of us hears is our mother’s heartbeat, within the womb: a signal of the beginning of new life, the pulse that keeps blood pumping. A similar sound greeted attendees of Pink Floyd’s legendary four-night stand at London’s Rainbow Theatre in February 1972, a harbinger of a potent rebirth that would deliver one of the best-selling albums in rock history.

-

READ MORE: Every Pink Floyd Album Ranked

For the members of Pink Floyd, that rebirth couldn’t come soon enough. Four years earlier, mercurial frontman Syd Barrett had exited the group under traumatic circumstances. And while the remaining members had righted the ship enough to keep it sailing on, the group seemed suspended in a creatively uninspired space-rock orbit. As drummer Nick Mason drolly remembered, as 1971 closed Pink Floyd were “in acute danger of dying from boredom”.

But it’s always darkest before the dawn. And in that bleakest midwinter, the group had composed a 10-track suite of new material, with which they opened shows through a month-long tour of the UK. It was a bold move that the Floyd didn’t undertake lightly, rehearsing for two weeks at The Rolling Stones’ practice space in Bermondsey, before spending several days putting their new PA system through its paces at the Rainbow. All that preparedness didn’t prevent the very first performance snatching defeat from the jaws of victory, as on the opening night of the tour, at the Dome in Brighton, the group’s sound effects tapes ran fatally out of sync a few songs in, leaving a shaken Roger Waters to stammer, “Due to severe mechanical and electrical horror, we can’t do any more of that.”

When the group returned to the Rainbow for the new material’s London premiere a month later, the technical difficulties had been ironed out. There were some minor differences between the songs as played that night and the album that would later shift over 45 million copies. On The Run, then titled The Travel Sequence, was a jazzy, jammy thing, missing its signature swarming synth-lines; The Great Gig In The Sky was an embryonic jam called The Mortality Sequence, its wailing vocals absent; the saxophones that would lend emphasis and mood to Us And Them and Money were also missing, as too were the haunting samples of monologue that would punctuate the finished opus.

What mattered, however, were the elements that were present on that night: songs that took the dreamy, cosmic sprawl of Pink Floyd’s progressive sounds and anchored them to larger truths, bigger pictures and mortal profundities. “My big fight in Pink Floyd,” Waters later told journalist John Harris, “was to try and drag it, kicking and screaming, back from the whimsy that Syd was into – as beautiful as it is – into my concerns, which were more political and philosophical.” No longer inspired merely by lysergic experimentation or poetic stargazing, these new songs drew upon dark fears, mental illness, and the moral and spiritual negotiations made along the passage into adulthood. The result was an emotional resonance that had previously eluded the group in their psychedelic guise.

At the Rainbow, the closing notes of Eclipse, the suite’s final song, gave way to tape loops of disembodied voices and an air-raid siren slowly winding down. There was a hushed awe, then rapturous applause. The London press premiere, subtitled for these performances A Piece For Assorted Lunatics, was an unalloyed triumph. Once recorded and released, the material would go on to reshape Pink Floyd’s destiny, recasting the Barrett era – the all-consuming shadow that the group had been trying to escape – as mere prelude for The Dark Side Of The Moon and all it would bring.

But the very success the album heralded would ultimately alienate Waters from the audience it won him and prefigure his exit from the group he founded.

For the first time we were earning more than our roadies.

David Gilmour

IT'S NOVEMBER 1971 AND, days after completing a North American tour, the members of Pink Floyd are gathered in the kitchen of drummer Nick Mason’s Camden home, to discuss their next step. A change of course is necessary, they feel, even though their current trajectory is remunerating the quartet handsomely. Their albums since Syd’s exit – 1969’s half-live/half-studio Ummagumma, 1970’s cod-symphonic Atom Heart Mother and 1971’s experimental Meddle, not to mention their 1969 soundtrack to Barbet Schroeder’s directorial debut More – all reached the UK Top 10, with Atom Heart Mother topping the chart and helping pay off the enormous debts the group had accrued in their early days.

“For the first time, we are earning more than our roadies,” laughed David Gilmour. Despite this newfound financial security, Pink Floyd had mixed feelings towards the output that got them there. “We were fairly brave and would put anything on a record that amused us one way or another,” Gilmour would later reflect. “But in some of those moments we were floundering about, and inspiration might have been a bit thin on the ground.” Atom Heart Mother, Gilmour added, was “probably our lowest point, artistically”.

Meddle, however, marked for Gilmour “the point at which we found our focus”. Specifically, he was referencing Echoes, an exquisitely excursive, and discursive, 24-minute epic. For all its skyward-leaning musical invention, the track remained connected to terra firma via Waters’ lyrics, inspired by mornings spent gazing at faceless commuters bustling off to work, and thinking about “the potential human beings have for recognising each other’s humanity”. Like Echoes, much of the music they were about to compose would similarly concern the larger commonalities of the human experience, albeit refracted via Waters’ own perspective.

In the vacuum left by Syd’s departure, Waters had wrested control of Pink Floyd. “Roger was the ideas man and the motivator,” conceded Gilmour, the guitarist struggling to assert himself creatively in his early days with the band, still perhaps feeling cowed by a sense of being the ‘new boy’. And Waters was, by all accounts, a formidable competitor. “He could be very abrasive to those around him,” Ron Geesin, who helped orchestrate Atom Heart Mother, told Floyd biographer Mark Blake. “Most artists of any worth create abrasion around them – it’s necessary to create the heat for creativity.”

“Roger could be so frightening,” agreed Nick Mason, perhaps Waters’ closest companion within Floyd, who noted that the dynamic within the group was “akin to being in a small army unit or prep school, because you can oscillate so easily between love and hate. Jokes, and the way they become teasing and bullying. We can be incredibly spiteful.”

Waters took the lead on this embryonic new project. “The ‘big idea’ came before quite a number of the lyrics,” he recalled to MOJO in 2006. “I remember explaining it to the rest of the band: that the whole record might be about the pressures or preoccupations that divert us from our potential for positive action.” More recently, he’s described himself as having been fired up by “a strong, compelling notion that we could make an album about life, about feelings, the human condition and things that impinge upon us.”

To grapple with such big ideas, Waters reasoned, would require a concerted move away from Floyd’s current ‘cosmic’ approach. “I remember Roger saying that he wanted to write it absolutely straight, clear and direct,” Gilmour recalled. “To say exactly what he wanted for the first time, and get away from the psychedelic patter and mysterious warblings.” To do so, the bassist drew inspiration from his and his bandmates’ own lives, and how they were handling the transition from youth to manhood, a concept then consuming Waters. “I was 29, and I suddenly realised, this was life,” he remembered. “It was not a preparation for something else. This was not a rehearsal: life was happening now.”

There was a residue of Syd in all of this.

Roger Waters

These new songs, Waters decided, would “confront a number of major psychological and emotional concerns”. One of those psychological concerns was insanity, a common thread through the album, and the penultimate Brain Damage in particular. The spectre of madness was something that had long haunted the members of Pink Floyd, still troubled by their former frontman falling prey to mental illness after his experiences with LSD and their inability to help him.

“We had a style: ‘Ignore it’,” said Mason of the group’s method of dealing with Barrett’s worsening state. “Finally we ignored it by not picking Syd up [en route to show in Southampton] one day. I remember the relief, after Syd had gone.”

Pink Floyd’s 1975 album Wish You Were Here – and specifically Shine On You Crazy Diamond, the epic track that lay at its heart – would more explicitly take Barrett as its theme. But Syd’s shadow also hangs over The Dark Side Of The Moon in the group’s attempt to finally move on from his tragedy, and to come to terms with their sorrow and guilt.

“There was a residue of Syd in all this,” admitted Waters. “When you see that happening to someone you’ve been very close friends with, it concentrates one’s mind on how ephemeral one’s sensibilities and mental capacities can be. For me it was very much, ‘There but for the grace of God go I…’”

-

READ MORE: Pink Floyd rare and unseen pictures!

Shortly after that Camden kitchen pow-wow, the Floyd decamped to Decca’s studios in West Hampstead for two weeks, beginning work on the new material, then titled ‘Eclipse’. As was their tradition, they started by dusting down some unused ideas from the past: Us And Them had begun life as a piano piece Richard Wright had penned for the soundtrack to Michelangelo Antonioni’s 1969 movie Zabriskie Point, which the Italian auteur had rejected on the grounds that it was “beautiful, but it’s too sad, you know? It makes me think of church.”

Waters had begun Brain Damage during sessions for Meddle, but now brought a more evolved version of the song to Decca, along with a demo of Money, a dark blues punctuated by rudimentary sound effects, which Roger had knocked up in his home studio, located in his garden shed. Further new material took shape during these sessions, which were productive enough that, by the end of the fortnight, the group had rough versions of the entire suite ready to take on the road for a UK tour beginning in January 1972.

But despite the impressive work rate at Decca, the group would not complete recording The Dark Side Of The Moon until January of 1973, seven months after official sessions for the album began. Progress would be interrupted by a tour of Japan (where they continued to play the new piece in its entirety) in March 1972; sessions in France recording the soundtrack to Barbet Schroeder’s second movie La Vallée (released that summer as Obscured By Clouds and charting at Number 6 in the UK); a 17-date US tour in April; two Brighton shows in June, to make up for The Dark Side Of The Moon’s disastrous debut that January; the premiere of unorthodox concert movie Live At Pompeii, which presented the Floyd playing live, without an audience, in the ruins of the Roman amphitheatre; another US tour in September; and a jaunt around Europe in November.

Perhaps so grand a work as The Dark Side Of The Moon demanded this long gestation period for its ambitious vision to mature and for every element to be buffed to perfection. Lengthy sessions at Abbey Road saw the band self-producing in the company of engineer Alan Parsons, who manned the studio’s newly installed 16-track tape machines. A 1974 re-release of Live At Pompeii would include footage filmed during these sessions, depicting the group’s infamously vicious and dry sense of humour, which they turned on each other and filmmaker Adrian Maben. But an interview with Nick Mason also betrayed the anxiety helping to fuel the project.

“Unfortunately, we mark a sort of era,” he explained. “For some people we represent their childhood… We’re in danger of becoming a relic of the past.”

There were little signs of the rock’n’roll excesses practised by the Floyd’s contemporaries; as Waters once said, “unlike most bands we’re not heavily into crumpet” (although indiscretions on the road did spell the end of his first marriage), with the chief distractions taking the form of Arsenal matches and episodes of Monty Python on the telly. While the group were renowned for their penchant for improvisation, those hours spent in Abbey Road were comparatively focused. “The improvisation period had become a lot more structured,” Parsons told Mark Blake. “Mainly because they’d been playing The Dark Side Of The Moon live. They didn’t have to mess around with the compositions.”

That said, several songs took some serious evolutionary steps at Abbey Road, perhaps most notably On The Run, which had begun life as a traditional instrumental jam but then morphed into something that sounded as if it had materialised from the future. A piece of true abstract, avant-garde studio invention, On The Run’s creation was captured in footage from the expanded Live At Pompeii, with Waters messing about with a pair of VCS3 synthesizers – antiques now, but then very much cutting edge technology back in 1973.

Money, meanwhile, was on the surface a relatively trad blues stomp, though on closer inspection it switched from 7/4 time in its verse and chorus to 4/4 for its blistering guitar and saxophone solos, the latter the work of Dick Parry, whose mournful sax playing would lend further weight to the blissfully turbulent Us And Them.

It was Great Gig In The Sky that experienced the most striking transformation, however. Early live performances of the piece had paired a Richard Wright organ instrumental with loops of ponderous speeches by outspoken post-war journalist and intellectual Malcolm Muggeridge. For the studio version, however, Wright switched to piano, while session singer Clare Torry – who was not a Floyd fan – improvised howls, yells and wails over the top.

“They explained the album was about birth, and all the shit you go through in your life, and then death,” remembered Torry of her prep for the performance. “I did think it was rather pretentious.” Yet the finished recording transcended pretention, reaching some wordless, sublime place that encompassed both life’s agonies and ecstasies. Torry was paid a flat fee of £30 for her contribution, but successfully sued the group and their label EMI in 2004 for songwriting royalties.

Great Gig would be one of the final tracks completed, with Torry’s vocal laid down on January 21, 1973. But before The Dark Side Of The Moon would reach audiences, the group added some final touches. A series of spoken vignettes scattered throughout helped tie the songs together into a cohesive thematic whole, Waters having interviewed various guests at the sessions – roadies, friends, even Paul McCartney, also working at Abbey Road at the time with Wings – and asking them questions connected to the album’s themes. Waters felt the ex-Beatle was “trying too hard to be funny” so his contribution hit the cutting-room floor, but characters like Floyd roadies Roger ‘The Hat’ Manifold and Chris Adamson delivered unselfconscious replies that were, by turns, moving and unsettling, and therefore perfect for the project.

The group went to great lengths to ensure that, in the finished mix, Dark Side’s 10 songs flowed perfectly into each other. The end result recalled the unbroken song cycles of Sgt. Pepper or the second side of Abbey Road, though Waters was uncharacteristically humble in the face of such a comparison. “We felt that The Beatles were too good to compete with, honestly,” he said of his stellar labelmates. “Maybe that was encouragement, because they set the bar so high.”

Soon, however, millions of Floyd fans would agree that The Dark Side Of The Moon had decisively cleared that bar.

THE PRESS RECEPTION TO CELEBRATE the release of The Dark Side Of The Moon took place on February 27, 1973 at the London Planetarium but, mindful of the material’s debut a year or so earlier in Brighton, the group boycotted the event as they felt the sound system was too substandard to do the album justice (they were represented by life-sized cardboard cut-outs instead). The album reached shops two days later, already proclaimed a masterpiece by much of the music press, including a young Loyd Grossman, who, reviewing the album in Rolling Stone, praised “a certain grandeur here that exceeds mere musical melodramatics and is rarely attempted in rock”. It would top charts the world over, remaining on the Billboard US Top 100 for an incredible 741 weeks.

Ultimately, Dark Side… would go on to sell over 45 million copies, transforming Pink Floyd from cultish egghead mavericks to stadium-level rock stars. Perhaps inevitably, the iconoclastic Waters chafed at this transition. “It took me until 10 years ago to stop being upset that people whistled through the quiet numbers,” he grumbled to MOJO in 2006. “I used to stop and go, Right! Who’s whistling? Come on – be quiet!”

Life on the stadium-rock treadmill would swiftly turn into a grind for Waters; one infamous low-point, where he spat contemptuously upon the audience during a 1977 concert, inspired Floyd’s disaffected 1979 concept album The Wall. Behind the scenes, the same creative tensions that had sparked Dark Side… into life soon became untenable, and arguments over credit, division of labour and the creative direction of the band saw Waters exit the line-up in 1985, in an ultimately failed attempt to bring Pink Floyd to a close.

But these disappointments lay in the future. Having reconnected Pink Floyd with their muse and revived a band stuck in its space-rock rut, the Roger Waters of 1973 felt justified pride over The Dark Side Of The Moon. His wife Judy burst into tears after she heard the album in full for the first time, which, Waters said, he took as “a very good sign. I had a very strong feeling when we finished the record that we’d come up with something very, very special.”