As guitarist and songwriter for The Band, Robbie Robertson helped shift the very foundations upon which rock and roll was rooted, both as sideman to Bob Dylan when he went electric and through his own group’s remarkable music. Music that dug deep below those foundations to uncover a new musical lexicon and vision of American music, one steeped in its rich cultural history. In 2017, MOJO’s Michael Simmons sat down to hear Robertson’s story. A tale lit-up by diamond smuggling uncles, gay pot dealers, and even an actual armed robbery he planned to commit, his testimony was a wild witness statement from rock’s frontier phase, but it veiled and aftermath of bitterness and heartache.

READ MORE: Bob Dylan's Greatest Songs, as chosen by Paul McCartney, Patti Smith, Nick Cave and more!

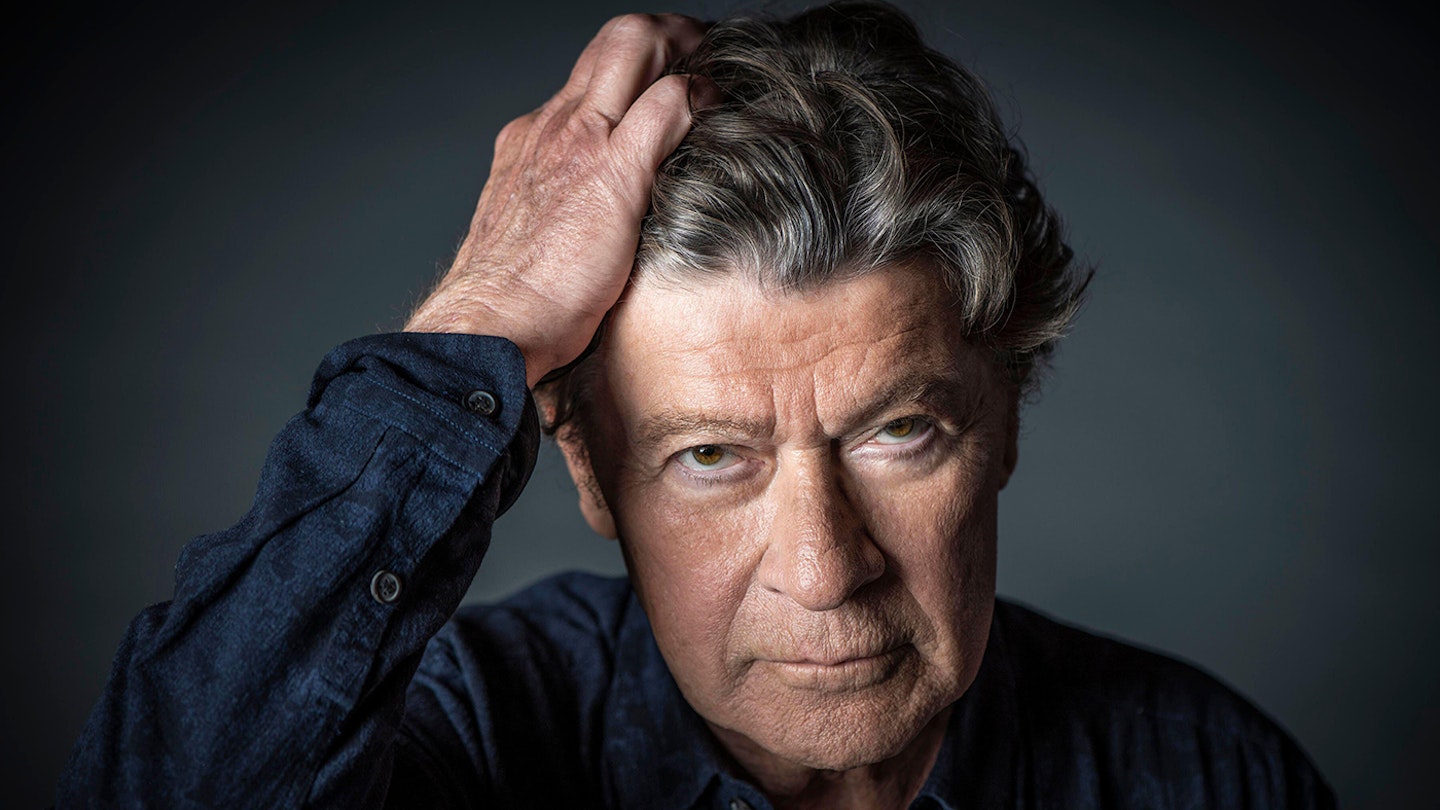

DECKED OUT IN AN ALL-BLACK suit, Robbie Robertson exudes elegance and a well-read intelligence, – the latter all the more fascinating given his teenage education chicken- pickin’ in honky-tonks where – in the words of his first major employer Ronnie Hawkins – “You had to show your razor and puke twice before they’d let you in the door.” We’re meeting at his small office in a nondescript Los Angeles neighbourhood. Propped against a wall is the Martin D-28 acoustic on which he wrote The Weight and in a corner the Fender Twin Reverb amp that survived Woodstock and The Last Waltz.

“Talking-one-two, talking-talking-talking,” Robertson says into MOJO’s tape recorder, checking levels in a raspy baritone. The recorder is working and Robertson’s been too. He’s penned a new memoir called Testimony (“penned” is literal – he wrote it longhand), its title a statement that the private songwriter-guitarist is going to open up. Robertson’s formative role in rock is unquestioned – from his beginnings as an adolescent proto-shredding Telecaster master, through his crucial complicity in Bob Dylan’s rock reinvention and the unsurpassed rootsy originality of The Band. But others – notably Band drummer Levon Helm – have published their accounts of the era. Helm, in particular, was bitterly critical.

Half-First Nations (ie. Indian), half-Jewish, Robertson grew up in Toronto, Canada and, like many 1950s kids, his future was determined by a Christmas guitar and Be-Bop-A-Lula on the soda shop jukebox. On a trip north of the border, Arkansas rockabilly raver Ronnie Hawkins first crossed paths with the 16-year-old when the kid was in opening act The Suedes and later hired him as bassist for his backing group The Hawks; Robertson’s rhythm section partner was another Arkansan, Levon Helm. In Testimony, Robertson writes that Hawkins had big plans for the youngster from the start, taking him on a song-hunting mission to New York’s Brill Building. When Robbie asked why he wasn’t taking Levon, Hawkins said of Helm, “He ain’t a song person.” These five words would have implications later.

“I was writing songs before I knew I was writing songs,” Robertson tells MOJO. “I was trying to figure out a guitar part on a song when I was quite young, and I got so frustrated with it. I thought, The hell with it – I’ll just make up a song. So I’d just write a song because it was a short cut. I wrote songs ’cos I had to. Ronnie says to me, ‘Levon’ll play it better than anybody, but he isn’t really the kinda guy who goes out in search of songs and cares about it, he’s like, Let’s just play.’”

Hawkins was adopted as a Toronto rocker in the early ’60s. The Hawks evolved into Robbie, Levon, bassist/singer Rick Danko, pianist/singer Richard Manuel and organist/saxophonist Garth Hudson. They’d become more than a band – they would be The Band. But first they’d be the most notorious sidemen in rock’n’roll.

Who Do You Love – the single Ronnie Hawkins and The Hawks cut in 1963 with your hellfire solo – sounded like it came out of nowhere.

(Laughs) It came from a very youthful spirit – there’s no patience involved. Whenever it was time for me to blow Ronnie’s mind – to do something that would make him just scream – I couldn’t wait. And so, that energy, that excitement, that teeth-grinding screaming guitar was something that takes a certain amount of youth.

There’s that famous Dylan quote, calling you a “mathematical guitar genius”. What do you think he meant by “mathematical”?

It’s having a structure [that’s] improvised and at the same time you have a sense of dynamics – when to rise, when to fall, when to shimmer, when to growl. When The Hawks hooked up with Dylan, he found this explosive, dynamic thing. Because of his intensity, it raised everything up and we didn’t come down enough and people were saying this music is so loud we can’t hear the words. Part of that was he wanted that raging spirit on these songs.

We got booed all over North America, Australia, Europe, and people were saying this isn’t working and we kept on and Bob didn’t budge. We got to a place where we would listen to these tapes and say, “You know what? They’re wrong. And we’re right.” Eight years later, we do a tour, the [1974] Dylan/Band tour, we play the same way, same intensity and everybody says, “Wow, that was amazing.” The world came around – we didn’t change a note.

There’s a line in your book, “This wasn’t the folk traditionalist Dylan; this was the emergence of a new species.” What did you learn from Bob in 1965 and ’66?

The obvious thing we learned – that everybody learned – was there was a new way of songwriting. There was a much more colourful, descriptive, humorous, outrageous thrill ride of wordplay. We hadn’t seen this before – this was breaking some big rules. I remember saying to Bob one time, “Maybe there’s too many verses in this” (laughs), and he said, “There probably are, but that’s what I was thinking about when I wrote it.” His spirit was on fire, and he was knocking down the boundaries that had been built up around music. It excited me to be part of this revolution.

Levon didn’t like it at first and left The Hawks for a while. Besides the booing, what didn’t he like?

He didn’t like the music, he didn’t like the songs – at that time. He didn’t like the fame game that was going on with Dylan because it didn’t feel real to him. He wasn’t comfortable in New York City, he wasn’t comfortable around that many Jews. I write about this when he’s telling me he wants to leave and he says, “I don’t like this goddamn music, I don’t like Albert Grossman, and I don’t like being surrounded by all these goddamn…” And he stopped himself, but I knew where he was going and I thought, You don’t get it, or you don’t want to get it.

FOLLOWING THE DYLAN TOUR/ORDEAL OF 1966, The Hawks retreated to a basement in Woodstock, New York. Music From Big Pink and The Band of 1968 and ’69 followed – a one-two knockout punch. The first filtered American roots music through an ethereal dream state, the second was more literal – an American history lesson conjured by Robertson and Manuel’s songs and told through the eyes of fictional participants. The records irrevocably changed the trajectory of rock.

Meanwhile, the emotional content of Robertson’s songs – steeped in tradition, filled with boisterous sexuality, defiant pride and inconsolable regret – had precedence in his own life. His First Nations mother carried stories and rituals from before the white man’s conquering of North America, while his blood father’s brother was mobbed-up in murky, illegal rackets involving black market diamonds – with a prominent family in Toronto’s Cosa Nostra as partners. This led to Robertson’s close-call as a would-be mob bagman, delivering diamonds for his uncle. The deal was aborted, as was a later caper when he and Levon planned to knock over an illicit card game. Armed and masked, the two future Band-mates arrived at the scene of the proposed crime, only to find the game had been cancelled. Robertson’s memoir reveals someone who was clearly more than a dilettante with a library card.

In 1968, Music From Big Pink was so different to anything else. It still is.

Something happened in that basement. We weren’t playing to an audience, we were playing to one another, and we were in a circle. If you couldn’t hear somebody singing, it meant you were playing too loud. So we found a subtlety, it made you hold your breath – ahhh. Energy and power and excitement and violence had a lot to do with our music. Now, there was a different sensibility. And the songs that I was writing, if you played too hard, it was out of context. All of these things started to have a new kind of grace. Everybody else was getting louder and we’re going to this other place and there was a delicacy to it. Little things meant more than the obvious. All of these musicalities we heard – fife-and-drum blues, mountain music, Delta, Anglican choirs, rockabilly, Johnny Cash – the simplicity is exquisite. The Staple Singers when they sang gospel and it’s just the voices and Roebuck’s guitar… Curtis Mayfield. And jazz – Charles Lloyd. All of this we’re gathering and all of it makes this new music.

There’s also something spooky about it – otherworldly, impenetrable.

It was cinematic. You not only could hear it, you could see it. It had a sound that we had never heard before. Voices were used in a way that we hadn’t heard before. Instruments were played with a delicacy that pulled at your heartstrings and it had this beautiful sadness to it. The more we got lost in that movie, Big Pink, the more comfortable it felt.

Big Pink comes out and The Beatles and Clapton come banging on your door. Did you realise you’d created something special?

We realised that it was touching people in the way that we hoped, but at the same time we were suspicious of success. Most of the stuff we really liked, not a lot of people knew about it and that’s what was golden about it. So when we put out …Big Pink, on one hand you think, Isn’t it wonderful that people are embracing this, but at the same time we would never look at the charts. That’s where you go wrong, when you start thinking about this as a popularity contest. So sure enough, at a certain point we became successful and things changed and it hurt people personally. The more successful we got, the more self-destructive we got.

On the second album, you write about things you couldn’t have known about – like turning 73. Of course, you’re now 73. Where did these songs come from?

On The Band record, I wasn’t writing personal songs, I was telling stories. We’d be driving down a highway and I’d see a little house off in a field, and I’d think there’s a light on there – what’s going on in that house? Some of it was reflective of periods in the South because I was 16 years old when I went from Canada to the Mississippi Delta and it made a huge impression on me, ’cos I thought, I’m going to the Holy Land, I’m going where this stuff grows out of the ground. It was like writing a movie script.

One of the stories in the book is you and Levon attempting an armed robbery.

In the world that we ran in, we knew so many people from dark places, criminals that were really good at it, thieves [who] took great pride in their gift. They were friends of ours, they came to where we played. Now this is big cities up north. In the South was a different kind of criminal. I tell the story about when Levon and I score some grass with this guy that’s got fingers missing. He takes us out into the country and these two old guys are out there…

The gay pot dealers?

Yeah, and the guy’s shooting heroin in his neck. They weren’t feminine. They were guys who had spent most of their life in prison – for them, it’s a different kind of gay. It’s like, I fuck whatever I can, whether it’s you or a tree. All of these characters [we met] – playing for Jack Ruby in his club with a one-armed go-go dancer and then a month later he kills Oswald. The circles we ran in made this idea of Levon and I doing this robbery not that far-fetched. We weren’t that different from these people. On both sides of the tracks, they like breaking the rules, they like getting away with stuff that’s naughty.

ROBERTSON’S TESTIMONY ENDS WITH THE LAST Waltz in 1976 – the all-star show at San Francisco’s Winterland that was filmed by Martin Scorsese and turned into a definitive document of rock. But it wasn’t the end of The Band. After various solo projects, the group hit the road again in 1983, without Robertson, and recorded, notably 1993’s Jericho – a little gem. In 2016, three are too soon gone: Richard Manuel by his own hand in 1986, Rick Danko from heart failure in 1999 and Helm in 2012 from a return of the cancer he was thought to have beaten over a decade before. Robertson has released several solo albums, written children’s books and worked with Martin Scorsese on film music, while Garth Hudson continues to compose and record.

The Robertson-Helm bond had been one of The Band’s anchors. “They each shared a part of the other’s soul,” Helm’s ex, Libby Titus-Fagen, told Band biographer Barney Hoskyns. “One would start a sentence and the other would finish it. They had their own alphabet, their own clock, their own DNA, a Levon-Robbie double helix.” And yet many Band fans have taken sides, some blaming Robertson for alleged transgressions in a relationship whose complexities they know nothing about. When the subject comes up now it’s clear he’s had enough. As he wrote in The Rumor from 1970’s Stage Fright album: “Maybe it’s a lie/Even if it’s a sin/They’ll repeat the rumor again.”

The big controversy among Band fans is the deterioration of your friendship with Levon. You went to see Levon when he was dying: was there any talk or exchange?

He wasn’t conscious, so all I could do was sit there and hold his hand and think about all of the amazing things that we had experienced together, and that he was still like the closest thing I’ve ever had to a real brother and that I loved him dearly. The negative thing between Levon and me happened 10 years after The Last Waltz. In all of the times that we were together, some of it’s loving and fabulous and some of it, [Levon’s] heroin [use], got in the way. Heroin will let you defy the truth and I did not understand that in our brotherhood. And it hurt me, you know, [but] I knew I had to learn to accept it.

But as time went on, something happened and he got bitter and paranoid. It drove the other guys in The Band crazy. They were like, “What the fuck now?” He thought everybody was trying to fool him and take advantage – concert promoters, accountants, lawyers, managers, Bob Dylan, everybody. This thing grew in him and it was like a plague, and I would say, “Listen, we’re keeping a real close eye, don’t worry about it, I know this is driving you nuts.” Then he started coming up with things we should do and our advisers said that’s not a good idea – he wanted us to build shopping centres in Arkansas.

It got to the point where I couldn’t discuss with him what we were going to do next because we weren’t getting anywhere. When it came time for The Last Waltz, a lot of which was done because Richard was in such bad shape that we knew he’s going to die – we gotta get out of the way. Plus, Levon and Rick were in bad shape. None of us were in great shape, but the three of them were in and out of a heroin thing.

It wore me down – I couldn’t do it. So I said, “Let’s bring this to a joyous musical conclusion because something has to be done.” And Levon’s thing became like a demon inside of him, eating him up. Everybody was having a lot of trouble with it, and it bothered me as much as anybody because I was the one closest to him. The Last Waltz was a relief – I didn’t have to babysit this every day [any more]. Levon wasn’t good at taking responsibility for his own part in it. Finally, 10 years after The Band, it became my fault.

What about Levon’s claims concerning songwriting credits?

There was never one discussion between the guys in the band about me not writing the songs. That would have been preposterous. I worked my ass off and they knew what I did and came to me and apologised for not holding up their end in that area. [Levon] made statements years after The Band that were just blatantly unfounded, and he’d never said one word to me about that in all of our times together. I chose to not say anything ’cos I knew that he was suffering from something and I didn’t want to turn this into anything. It broke my heart, but I knew it was untruthful, and of every song that I ever wrote for The Band, I wrote and brought to them, I never brought a song to them and said, “Can you help me finish this.” I finished some of their songs, but never once did [the opposite] happen. And he played a lesser part in the songwriting than anybody because, as we said earlier, it wasn’t his thing, it didn’t come naturally to him. So, he wrote Strawberry Wine and I helped him finish it, and I gave him credit on Life Is A Carnival and Jemima Surrender ’cos he was there, I loved him and I wanted to give him credit.

There are those – particularly some punk rockers – who’ve criticised The Band – and particularly The Last Waltz – as representing a tired ethos and being ‘Dinosaur Rock’. What’s your response?

Was Billie Holiday a dinosaur? Was Charlie Parker a dinosaur? These people changed the world. These people in The Last Waltz changed the fucking world. Some new people have done incredible work, but the jury’s still out on whether they changed the world. And I have great respect for The Clash. I’ve met some of those guys over the years and they worship The Band and told me, “That’s the stuff that made us wanna make powerful music and do it well.” And Elvis Costello, another one – and I knew the Sex Pistols, I knew Johnny [Lydon]. So I know you’re using “punk rock” as just a viewfinder towards something. But don’t ask me – ask them.

In the book you mention seeing John Coltrane perform, calling him “anti- showbiz.” That was my reaction every time I saw The Band in the day.

We didn’t play by anybody’s rules and when everybody was going in this direction of wearing big polka dots and silly clothes and screaming hate about their parents, The Band was taking pictures with our parents. We were dressing the way we dressed every day. Not because it was a look, but because we lived up in the mountains and you couldn’t wear polka dotty clothes – you’d look silly at the hardware store. We came from our own past, our own realness, and our own honesty. And then everybody started dressing like us!

This article originally appeared in MOJO 278

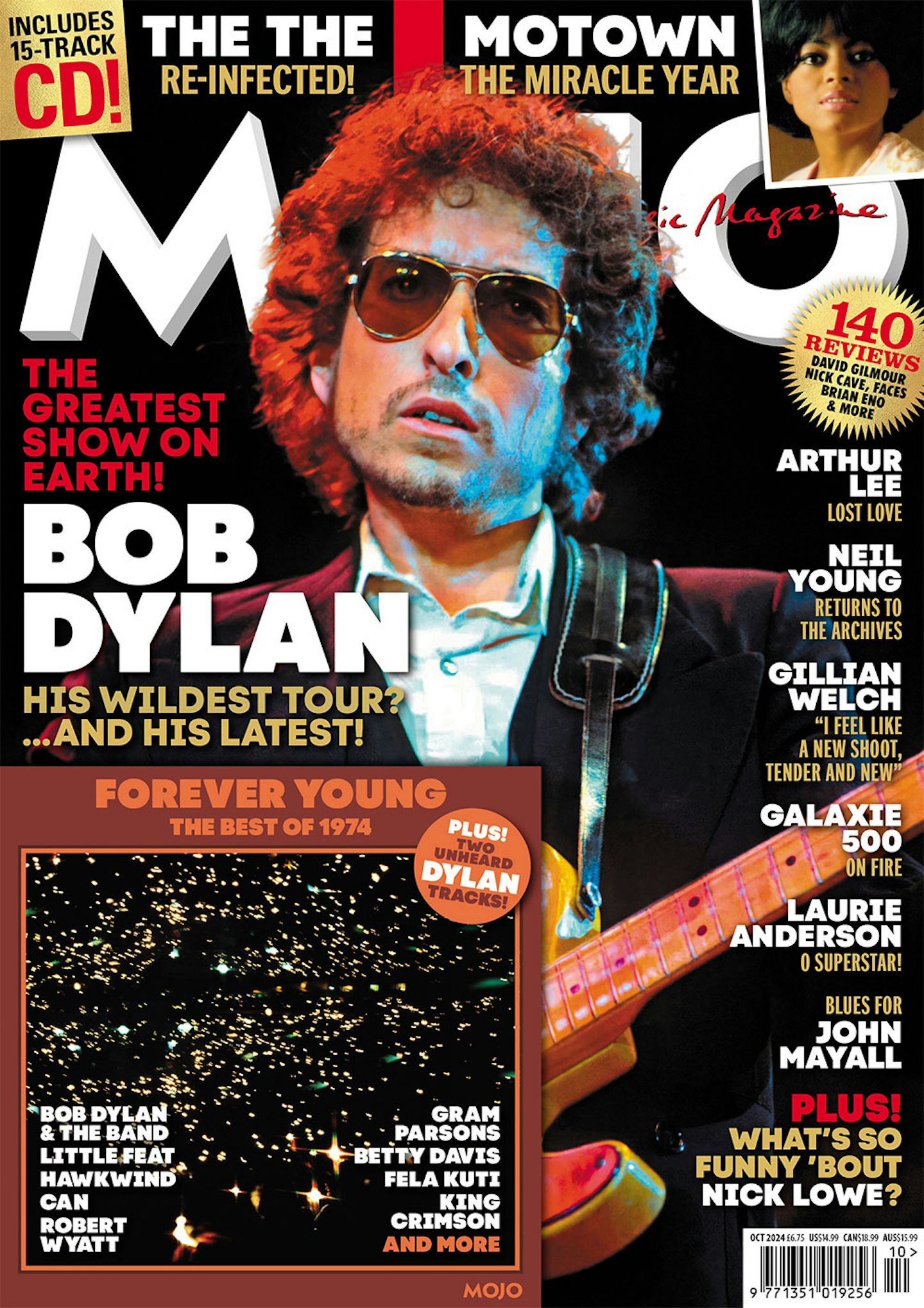

Order the new issue of MOJO now to read the real story behind Bob Dylan and The Band’s 1974 tour, as revealed by a new box set, new interviews and clues from the Dylan papers. PLUS! This month's exclusive covermount CD features two previously unreleased Dylan tracks from the tour! More information and to buy a copy HERE!